As a follow up to Tuesday’s post about single payer and redundant health administration workers, I believe it would be valuable to discuss labor turnover more extensively.

Labor Force Flows

When the jobs report comes out every month, we are accustomed to hearing things like “the economy added 150,000 jobs last month.” What most people don’t realize is that this figure is based on net jobs, meaning the number of jobs created minus the number of jobs destroyed. The actual amount of labor market turnover is far higher than that headline figure.

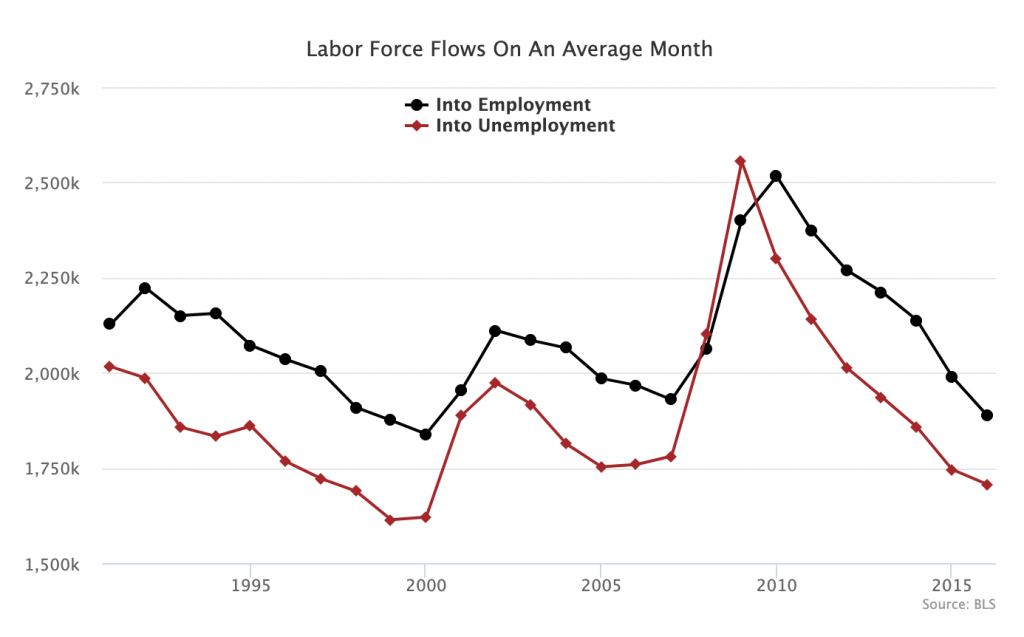

Consider the following graph based on BLS data. In it, we have how many people move from unemployment to employment (black line) and how many people move from employment to unemployment (red line) in an average month between 1991 and 2016.

As you can see, even in good times, the economy pushes 1.6 million people out of jobs and into unemployment every single month. But, conveniently enough, the economy also tends to push a somewhat higher number of people out of unemployment and into jobs every single month. This is how any kind of dynamic economy operates: workers get released from jobs and then reallocated into new jobs.

Of course, it is awful when people lose jobs and we need to increase the generosity of unemployment benefits and the extent of active labor market policies in this country. But when we are talking about making some health administration workers redundant, we need to put the numbers in perspective. Even if we were talking about releasing 1 million such workers from the sector over the course of a few years, that would be equal to around 19 days of normal labor flow activity in the US economy.

Job Seeking

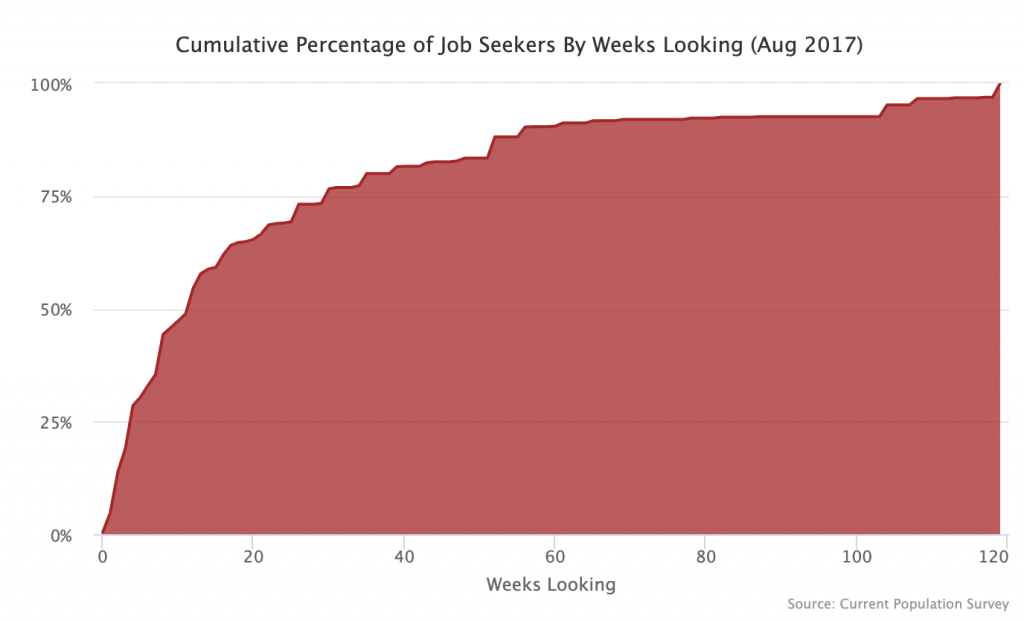

When people lose a job or enter the labor market for the first time, they become job seekers. So a natural question to ask is: how long does job seeking tend to take? One way to get at this question is to look at the distribution of job seekers by the number of weeks they have been looking for work, which I have done in the following graph.

About a quarter of job seekers have been looking for less than a month. Around half have been looking for less than 3 months. Around 90 percent have been looking for less than one year. This is not a perfect indicator of how long it takes to find a job of course, but it gives you at least some sense of the time we are talking about here.

Single payer proposals tend to include special unemployment benefits for those made redundant by the change. The most prominent such proposal, Conyers’ HR 676, provides for 2 years of unemployment benefits at 100 percent of salary. In the graph above, less than 5 percent of current job seekers have been looking for more than 2 years.

Applicable Skills

The ability to get a new job after an economic shift has changed the sector you worked in depends in significant part on how applicable your skills are to other sectors.

For instance, a coal miner who has only ever known digging coal and who has minimal other skills to draw upon can find themselves permanently locked out of the labor market if structural changes permanently reduce the number of available coal jobs or jobs featuring similar kinds of manual labor.

Health administration workers have skills that are applicable to basically every other sector in the economy. As I noted in the prior post, there are currently around 19 million Office and Administrative Support jobs in non-health care establishments. The precise content of office and administrative work varies sector to sector, but the basic skills to do it do not seem to.

Most Economic Reforms Are About Reallocating Workers

Finally, it is worth noting that basically every single economic reform anyone talks about is in some deeper way about reallocating workers in the economy. Think about it for a second. If your economic reform plan keeps the same workers doing the same tasks in the same jobs, then what exactly is it changing? How can the economy be different when workers are not doing different things than they used to do?

Consider the case of reducing income inequality in the country. No matter how you go about doing it, changing the distribution of income so that less income goes to the rich and more income goes to the middle and poor will lead to significant layoffs. Sectors that cater to the consumption desires of affluent people — housekeeping, yacht building, and SoulCycle instructing — will shed jobs when the rich have less money to pump into them. On the other end of things, sectors that meet the consumption desires of lower and middle class people will see more money flow into them, which will create jobs.

The net result of this kind of reform is a reallocation of workers out of rich-consumption sectors and into nonrich-consumption sectors. We don’t usually talk about reducing income inequality like this, but this is really the primary purpose of it.

The fact that nearly every economic reform involves the reallocation of workers does not mean that the frictions involved in reallocating workers don’t matter. They do and that’s why we should be pushing for generous unemployment benefits and active labor market policies as I noted already. But it is kind of ridiculous to say that single payer reforms are somehow uniquely problematic in this regard. They are not.

This is the second post in our Single Payer Myths series. The series tackles common arguments against a single payer system one at a time.