On one night every January, agencies across the country go out into communities and count the number of people considered homeless- both on the streets and in shelters. This count, the Point in Time (PIT), is used as the basis for the Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR), published by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The most recent AHAR, released in December 2017, showed an increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness for the first time in seven years. Vulnerable populations like the chronically homeless and those in unsheltered locations are growing. We should question why this problem remains so persistent despite a growing and flourishing economy, and what the current administration can and will do to solve it.

AHAR Report Key Findings

The most recent report showed important increases and decreases in specific populations that policymakers should pay attention to when considering how to continue tackling the problem of homelessness.

The following findings represent issues in the AHAR that need to be addressed immediately:

- There was an increase in chronic homelessness (12 percent increase over previous year).

- The increases in homelessness are mostly happening in metropolitan areas. The 50 largest cities accounted for almost all of the increase nationally.

- While the overall increase in homelessness was about one percent, there was a nine percent increase in homelessness in unsheltered locations (like the street or parks).

While the above points are discouraging, it should also be noted that the amount of people with children experiencing homelessness declined by five percent from the previous year.

| All People | Single Individuals | Families With Children | Unaccompanied Youth | Chronic Homeless | |

| 2017 Estimate | 553,742 | 369,081 | 184,661 | 40,799 | 86,962 |

| Change from 2016 | +1% | +4% | -5% | +12% | |

| Source: 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report | |||||

What the AHAR Is Missing

Shifting definitions of homelessness over the years and across different agencies have made it hard to compare and track housing outcomes. The AHAR is also based on an estimate gathered on a single night, which may not be representative of the true issue at hand. Homelessness, as defined in the AHAR, refers to unsheltered and sheltered individuals and families, but for these purposes “sheltered” means staying in an emergency or transitional shelter or a safe haven program. It does not count the millions of people who are unstably (and often unsafely) housed. The Department of Education, however, tracks school-aged children who are homeless in a different way, by including those who are unstably housed or “doubling up”. Taking this expanded definition into consideration, here’s what we know:

- Thirty-two (32) states have seen an increase in number of homeless students since 2012-13 school year, according to a recent DoE report.

- The number of identified, enrolled students reported as experiencing homelessness at some point during SY 2015-16 increased four percent over the last three school years.

- There are 1.3 million total enrolled homeless students, over one million of which are doubled-up due to loss of housing or economic hardship or staying in motels- neither of which should be seen as long-term, stable housing options.

The bottom line is that HUD is not including unstably housed families, who are especially at-risk, in the PIT count, causing underrepresentation of the problem in their report. We cannot hope to solve homelessness until we truly know how many people are experiencing unstable housing conditions and homelessness and are tracking this data consistently.

The 2019 Budget Issues

One of the main reasons for homelessness is an inadequate supply of affordable housing in every state. HUD currently utilizes rental assistance programs like the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program to ensure that low-income people, many of whom are elderly or have disabilities, are able to secure safe and stable housing. However, the President’s 2019 budget drastically cuts housing assistance programs, including Housing Choice Vouchers.

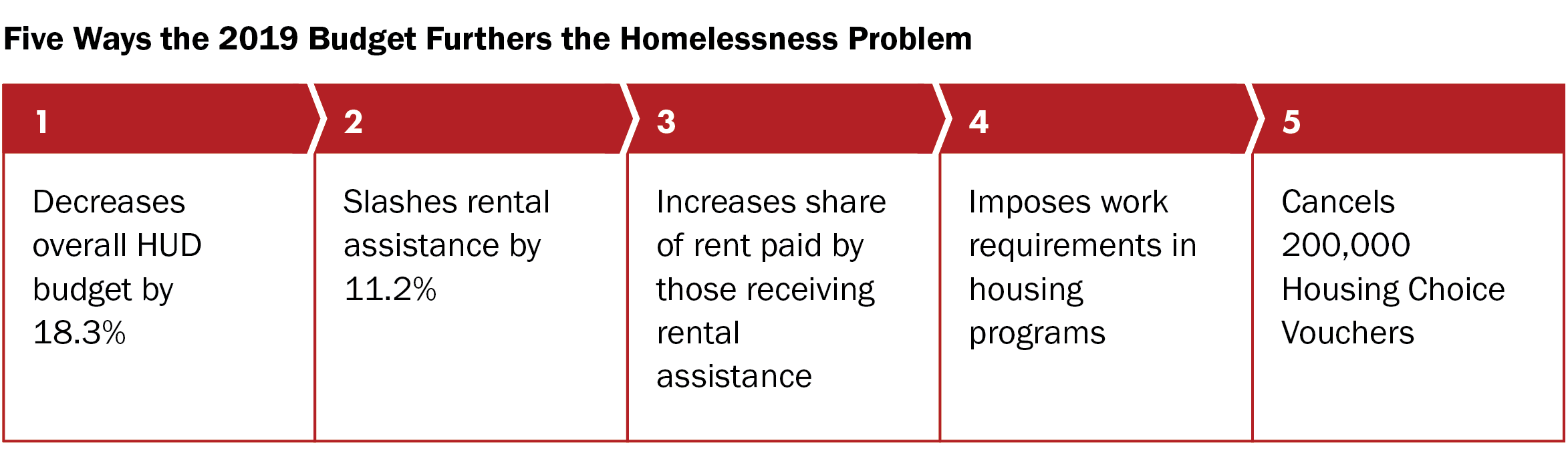

The President’s budget requests an $8.8 billion or 18.3-percent decrease in funding for HUD from the 2017 enacted level, with an 11.2 percent decrease (relative to 2017 levels) to rental assistance programs. He also wants to increase the share of rent that people receiving rental assistance pay, which is currently 30 percent of their gross income. Furthermore, the budget cuts funding for around 200,000 housing vouchers, which will likely lead to a rise in people being unstably housed or homeless. Finally, the budget allows housing authorities to impose work requirements on those receiving housing assistance. With the AHAR showing a rise in homelessness, how will cutting HUD’s overall funding and increasing the barriers to housing help families gain access to the safety and shelter they so desperately need?

What Can We Do Now?

When it comes to helping decrease homelessness, there are certain programs and models that we know work well. We should look to these evidence-based practices to inform HUD policy going forward:

- Housing Choice Vouchers: Allows voucher holder to choose where they live- whether that’s based on being close to where they work, their child’s school, or other factors, research shows that the ability to move to “high mobility”, lower-poverty neighborhoods where there is greater opportunity has lasting benefits for children well into their adult years.

- Housing First Programs for Chronically Homeless Individuals: These offer housing resources in a different way than other models by focusing on housing first and other services later (like mental health or substance abuse treatment). Utah has adopted a Housing First approach and chronic homelessness was reduced by 91 percent.

- Supportive Housing: The Veteran’s Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH) voucher program is a notable success, combining a housing voucher with other key services, and is largely responsible for cutting veterans’ homelessness almost in half.

In order to cut the number of homeless individuals and families we need to focus on expanding, not reducing, funding for programs. The administration should invest their resources in evidence-based approaches, like the ones mentioned above. Lastly, we must preserve existing affordable housing while increasing the overall supply, especially in metropolitan areas, where the recent AHAR noted increases in street and chronic homelessness.