The Center for American Progress released a new health plan they are calling Medicare Extra for All. The plan is a take on the old AmeriCare proposal, which has most recently been promoted by Jon Walker, Mike Konczal, and Tim Faust (sort of). I also briefly discussed the idea in section 3c of my piece from September about various single payer paths. The basic thrust of all these plans is to create a federally-administered public option that goes into every existing health insurance market and gobbles up all the customers in those markets by inducing mass switching to the public option.

Insurance Changes

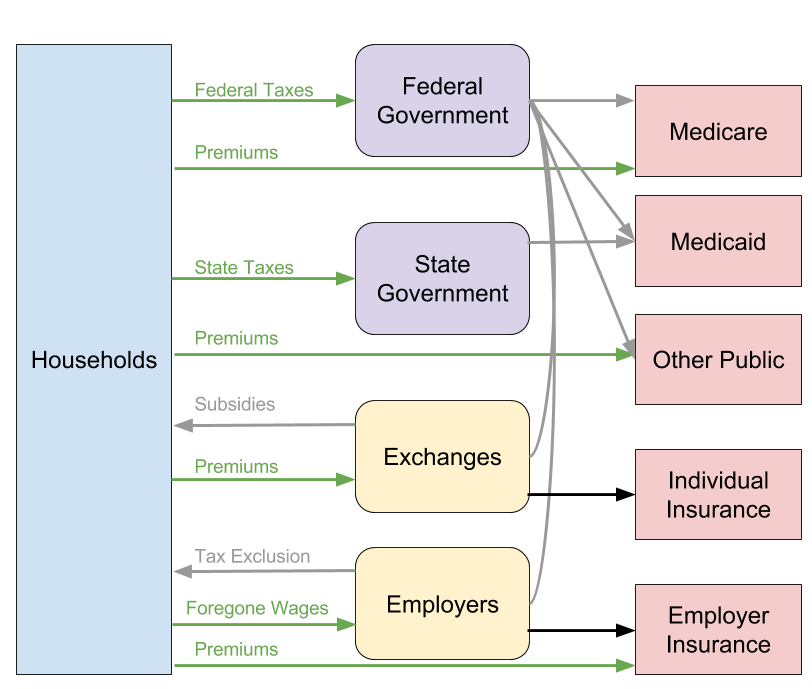

To understand the CAP version of this plan, it is helpful to start with our simplified schematic of the current US healthcare system.

Medicare. Those on Medicare would be rolled into the more generous Medicare Extra plan. Those with supplementary Medicare Advantage plans would see many of their supplementary benefits already baked into the new Medicare Extra plan. For supplementary benefits not baked into the Medicare Extra plan, there would be something called Medicare Choice, which people could pay an extra premium for just as they currently pay an extra premium for Medicare Advantage. (Edit: There is some unclarity in the proposal if Medicare Choice is meant to be supplementary or actually meant to allow private insurers to duplicate the core Medicare benefits. Here I assume the first interpretation.)

Medicaid. Those on Medicaid would get moved over to Medicare Extra.

Other Public. People on TRICARE or VA would have the option to move onto Medicare Extra or stay on TRICARE or VA. People on the Indian Health Service would stay on the IHS but could supplement their benefits with Medicare Extra.

Individual Insurance. Those getting insurance on the exchanges would get moved over to Medicare Extra. The plan states that “with the exception of employer-sponsored insurance, private insurance companies would be prohibited from duplicating Medicare Extra benefits.” This means that, unlike some other public option plans, Medicare Extra would not just compete in the individual exchange market, but rather annihilate that market by forbidding private insurers from offering benefits that duplicate what Medicare Extra offers.

Employer Insurance. Employers could continue to provide private insurance (assuming they do that) or force their employees onto Medicare Extra. Employees will always have the option of enrolling in Medicare Extra even if an employer chooses to only offer private insurance.

Notably, this plan completely replaces the two major coverage prongs of Obamacare: Medicaid expansion and the individual health care exchanges.

Money

Interestingly, the money side of things is fairly similar to sophisticated single payer proposals, the same ones that often get slammed by liberal critics.

Provider Payments. The payment rates to providers would be set equal to the current average of Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance rates minus one percentage point. This generates immediate cost savings in overall health expenditures and, since Medicare Extra will control provider rate growth going forward, makes it fairly easy to hold down health expenditures over time. The plan also provides for higher reimbursement rates in rural areas to ensure the viability of rural facilities.

Prescription Drugs. Medicare Extra would generate savings by cramming down prescription drug prices through monopsonistic bargaining.

Administrative Savings. Medicare Extra would generate savings through superior administrative efficiency, which public plans like Medicare already have.

Single payer advocates have long argued that there is already enough money in the healthcare system to fund the vast majority of a single payer program and that what remains could be made up through progressive income tax hikes. This also has often been laughed off by liberal critics, but nonetheless has been adopted by the Medicare Extra plan.

Employer levies. Medicare Extra plans to impound a large chunk of the $485 billion employers currently pump into the system through so-called maintenance-of-effort payments (don’t call them employer-side taxes!). Employers would contribute these levies by (1) paying 70 percent of the Medicare Extra premium, (2) paying an amount equal to their health spending the year prior to the enactment of Medicare Extra adjusted for health inflation and the number of employees, or (3) paying an amount equal to 0 to 8 percent of their payroll depending on employer size (don’t call it a payroll tax!).

Individual levies. Medicare Extra would charge individuals an income-based premium that ranges from 0% to 10% (don’t call it an income tax!). It would also make up any gaps through extra taxes on the rich.

State Payments. States would be required to take the money they currently spend on Medicaid and contribute it to the federal government. Footnote 22 says “if a state does not make maintenance-of-effort payments, residents of the state would not be eligible for Medicare Extra, and no federal health care payments, including to medical providers, would flow to the state.” This is almost certainly unconstitutional under NFIB v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court case that ruled that the Medicaid expansion of Obamacare was unconstitutionally coercive. I do not know how CAP intends to resolve this, but it’s not a technically complicated problem: just increase federal taxes to cover the amount states used to contribute to Medicaid and then let the states use the money they save from no longer providing Medicaid to cut state taxes.

Thus, when you put it all together, the CAP financing plan is really to use employer-side taxes, progressive individual income taxes including some special levies on the rich, and then state maintenance-of effort payments that are probably unconstitutional and so would need to be converted to actual federal taxes. Astute observers will notice a striking similarity to the Bernie Sanders proposal with the only difference being that Bernie actually calls a tax a tax while CAP calls only the special levies on the rich a tax.

Initial Thoughts

Before getting into the particulars, it is worth noting that CAP’s signing on to an AmeriCare-type proposal is the result of successful single payer advocacy. Back when everyone thought Hillary Clinton was going to win, New America’s Mark Schmitt penned an op-ed in the New York Times claiming that Bernie Sanders’ single-payer push was like Windows 95 in its outdatedness:

But the biggest reason that Mr. Sanders won’t shape the next progressive agenda stems from a little-noticed aspect of his campaign: His policy proposals were consistently out of step with the ideas that have been emerging from progressive think tanks like Demos or the Center for American Progress or championed by his own congressional colleagues.

For example, many liberal Democrats would agree with Mr. Sanders, in theory, that single-payer health insurance could be fairer, more efficient and cheaper than our fragmented system. But the president and Congress made the decision in 2010 to build on the private insurance system, in the form of the Affordable Care Act, in part because single-payer wasn’t politically viable. A Democratic administration’s next moves will be to expand and strengthen the Affordable Care Act, not start over.

At the time, I noted that Schmitt has his causation all backwards:

Think tanks are not independent institutions that impartially develop a body of ideas. They develop ideas that reflect the interests and perspectives of their donor bases and the political environments in which they operate. They can and do transform when conditions require them to do so.

If Sanders’s political revolution really did come to pass, there is little doubt the auxiliary political institutions would follow.

Sanders, National Nurses United, and other single-payer advocates managed to get most of the conceivable 2020 Democratic nominees for president to sign on to the single-payer idea and, lo and behold, CAP now has a single-payerish plan that scraps the core insurance elements of the Affordable Care Act.

When it comes to the substance of the plan, it’s useful to distinguish between different periods of hypothetical enactment.

During the transition period before almost everyone has switched to Medicare Extra, there will be unnecessary health expenditures in the form of administrative costs, high private insurance provider payments, and high private prescription drug payments. But this is true of any transitionary period towards single payer, including Sanders’s four-year transition period. The most that can be said on this point is that the transition period should be accelerated.

After the transition period, there are two hypothetical outcomes. The first (less likely) outcome is that, for some reason, the mass switching has not materialized and there are still a sizable number of people on private insurance. This would be uniquely bad because it would permanently preserve the problems of the transitionary period and because it could create a two-tier insurance system. The second (more likely) hypothetical outcome is that the mass switching does occur and Medicare Extra enrolls almost everyone. In that outcome, the main problem is that Medicare Extra’s out-of-pocket expenses may be too high (plans for higher-income people will have an actuarial value of 80%). This could be fixed by simply dialing down the cost-sharing, perhaps to zero.

Ultimately, I suspect the chief benefit of the CAP plan will not be found in its slight substantive differences from other plans but rather in the way in which the CAP brand is able to generate positive reception among validators.

At its core, Medicare Extra intends to use employer-side payroll taxes and progressive individual income taxes to enroll everyone on to a single public insurance plan. It primarily differs from other single payer plans only in that its transitionary period takes the form of inducing employers to switch over all of their workers to Medicare Extra rather than taking the form of phasing in age groups, as Sanders proposes. But because it’s CAP, the reflexive hostility to single payer plans that you get when leftist types propose them is gone.

For instance, consider this reception from David Leonhardt at the New York Times, which is titled A Better Single-Payer Plan:

The crucial difference between the Sanders plan and the CAP plan is that the CAP version would not force people to give up their current employer insurance coverage. Those who are covered through their jobs could either keep that plan or enroll in Medicare Extra. The Sanders plan, by contrast, would eliminate employer-provided insurance in favor of a single federal system.

This paragraph is factually untrue of course. The CAP version absolutely does force people to give up their current employer insurance coverage. Under the plan, employers will be able to eliminate their current plans and force all their workers onto Medicare Extra. Not only will they be able to do so, but this is the whole goal of the AmeriCare-type proposals. The mechanism that will cause most people to move over to Medicare Extra is that their employers force them to move over.

When you get the letter in the mail that says “due to the new healthcare law, you will now be enrolled in Medicare Extra,” it makes no difference whether it is on government letterhead or employer letterhead. You still are being “forced” to change over because someone else has made the decision that you will be on Medicare Extra and there is nothing you can do about it. But Leonhardt’s sympathies seem to blind him to this reality and most other liberal validators will also probably respond similarly. This is kind of silly in some cosmic sense, but as many on the left are eager to note, politics is not about sober policy analysis. To the extent that the CAP brand has that power, it’s welcome to see it employed towards ideas further to the left of the usual Obamacare dirge.