The US government has a spending problem. Given the country’s level of wealth, the government spends far too little — at least $1.6 trillion a year too little — on social welfare.

This exacerbates problems like poverty and inequality, and makes life a lot harder for a lot of people — from families with young children, to would-be college graduates, to the sick and elderly — than it should be. By leaving a large proportion of healthcare spending to the private sector, the United States has ended up with a healthcare system which does not even pass the basic test of universal coverage but is far more expensive than one that was publicly funded were at stake.

The best way to show this is to compare US social welfare with similar countries around the world. As a starting point, I use the OECD’s social expenditure database, which defines social spending as “cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services, and tax breaks with social purposes. Benefits may be targeted at low-income households, the elderly, disabled, sick, unemployed, or young persons.”

The database tracks both public social spending (think Medicaid) and private social spending (think employer-sponsored health insurance.) Adjustments are made for tax transformations — for example, in Denmark, the government offers very generous universal benefits, but then “claws back” a portion of these through either direct progressive taxation, or a more regressive consumption tax. So the final figures include these transformations.

I make two changes to the database figures. First, I add in public education expenditures. This is quite clearly “social spending,” as it involves a transfer of funds used to pay for a service consumed by households, so it should be included. (The OECD only includes education spending as a memorandum item in its full social spending report, as it has a separate database that tracks education spending.)

Next, I shift certain “tax breaks for social purposes” that are specifically designed to incentivize private social spending from the “net public” category to the “private” category. The biggest example of such a break is the tax exemption for employer-based health insurance, which gives tax breaks to employers for giving their employees healthcare coverage. I made this shift because these tax breaks are fundamentally a part of the private social-spending scheme. If the breaks were eliminated, private social spending would go down, and if private social spending were eliminated, the tax breaks would effectively disappear. They are not examples of the government spending directly on social transfers, but rather the government encouraging private social spending.

Public vs. private social spending

Private social spending is not really social spending. Think again about employer-sponsored health insurance. Really, this isn’t some kind of social-welfare benefit — it’s a form of compensation for wage labor. That is, if you don’t have a job, then you don’t get this benefit, and if you have a low-paying job that does by chance offer insurance, more of your overall compensation will go towards that “benefit” than if you had a high-paying job.

Thus, private “social spending” is, for the most part, regressive and narrowly distributed. Households are bearing the cost directly for the goods and services that they themselves consume like healthcare.

Public social spending is different. Often (though not always), it is a transfer of funds from the better-off to the worse-off. Think of a progressively funded, single-payer system. You will get health insurance whether you have a job or not, and if you have a low-paying job, it will cost proportionally less than if you had a high-paying job.

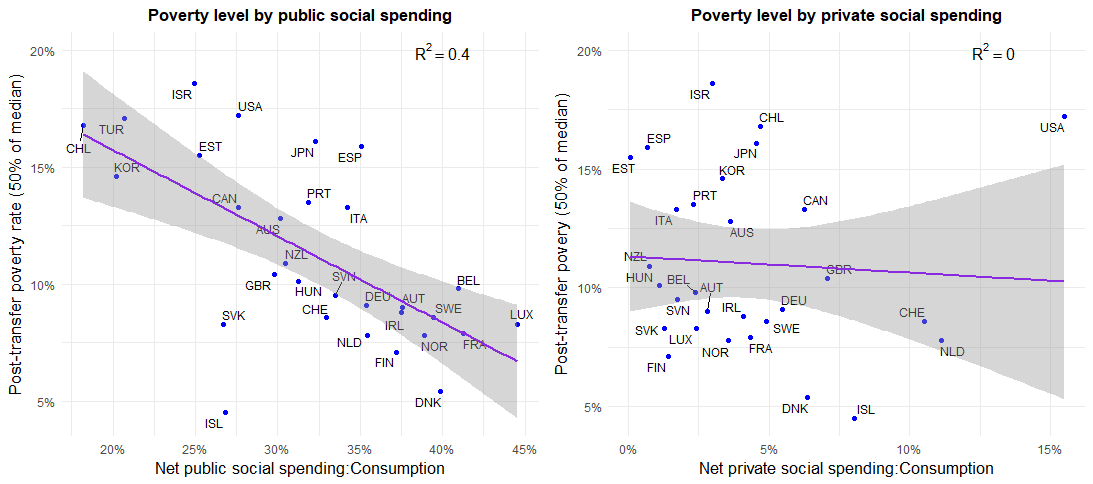

We can see the differences between private and public social spending in the following graphs. In the first set of graphs, we see, along the y-axis, disposable income poverty levels, as defined as 50 percent of median income. Along the x-axis, we see the share of a given country’s total consumption that goes to social spending — on the left, public social spending, and on the right, private. (For a brief explanation of why I am using “total consumption” rather than GDP, which is what is often used for such comparisons, see the technical note at the bottom of this post.)

It is quite evident from this set of graphs that there is a moderately strong relationship between final poverty levels and how much public social spending a country engages in. On the other hand, there is absolutely no relationship between private social spending and poverty levels.

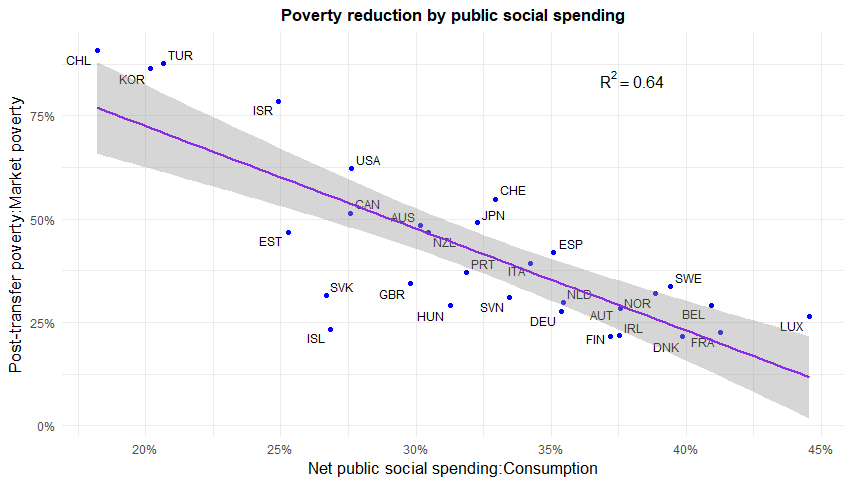

These graphs actually understate the effectiveness of public social spending, since they show final poverty levels. A given country may start with a higher or lower market poverty level, given a number of factors such as labor protections. It is enlightening then to look at how effective public social spending is in reducing poverty levels.

The following graph shows just this, with now final poverty level as a percentage of market poverty level along the y-axis:

There is a strong, direct relationship between public social spending and poverty reduction. This is even more impressive when you consider that “public social spending” does not automatically mean “progressive.”

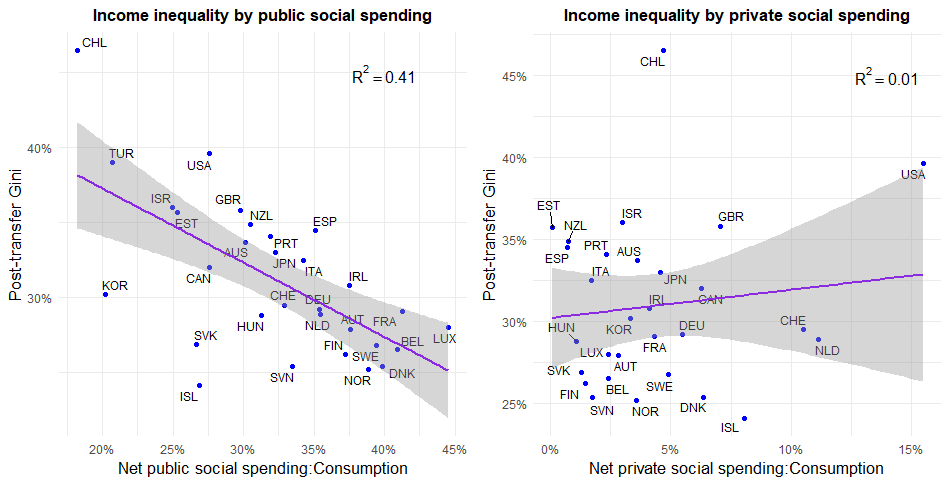

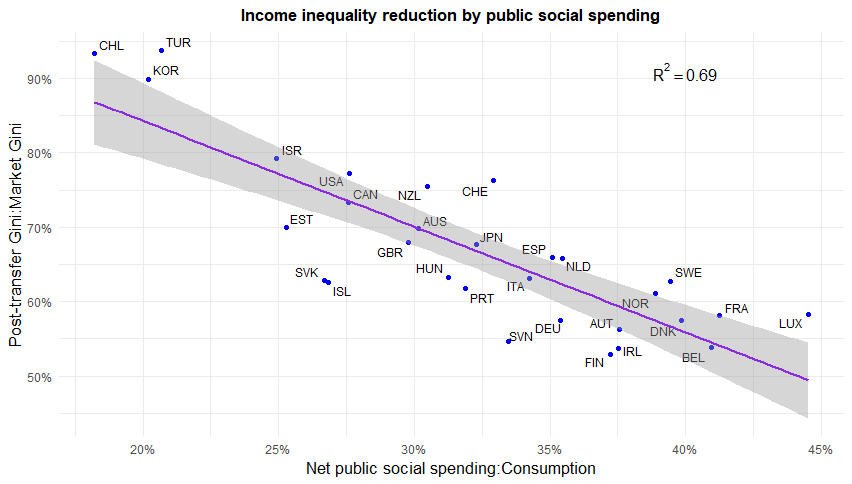

If we use a broader measure of income inequality, such as the Gini index, we see very similar trends:

We see then that public social spending does not just reduce poverty. It also creates a more equitable environment for society as a whole.

The U.S.’s terrible social welfare record

Now that we have begun to establish the importance of specifically public social spending, we can begin to answer the question: how bad is the U.S.? In short: it’s pretty bad. And the more you analyze it, the worse it gets.

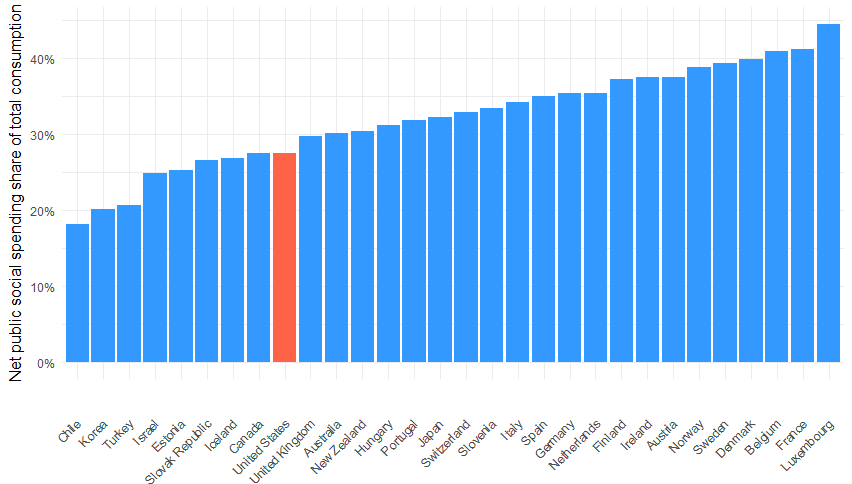

First, we can look at public social spending as a share of total consumption, and see how the U.S. compares to peer OECD countries:

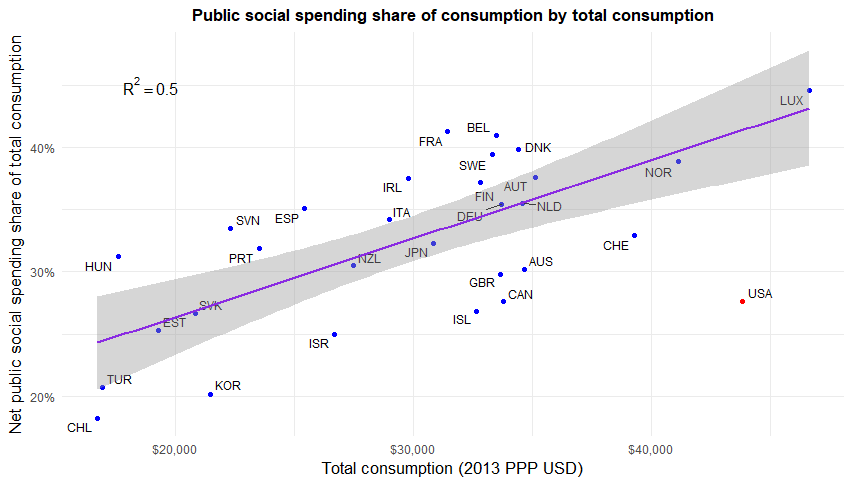

This looks bad, but at least the U.S. is not the worst. However, there is something else to consider, which is that as countries grow wealthier, they actually tend to spend proportionally more on social welfare. The following graph demonstrates this trend:

(Note that the U.S., represented by a red dot, is excluded from the regression line and the calculated R-squared presented here.)

We would expect, say, Chile and Turkey, to have a lower share of social spending, given the fact that they have relatively low levels of total consumption. This may or may not be theoretically justified, but it is the reality, for whatever reason.

But when we look at the U.S., we see that it only spends a slightly higher share of consumption on social welfare than these two countries.

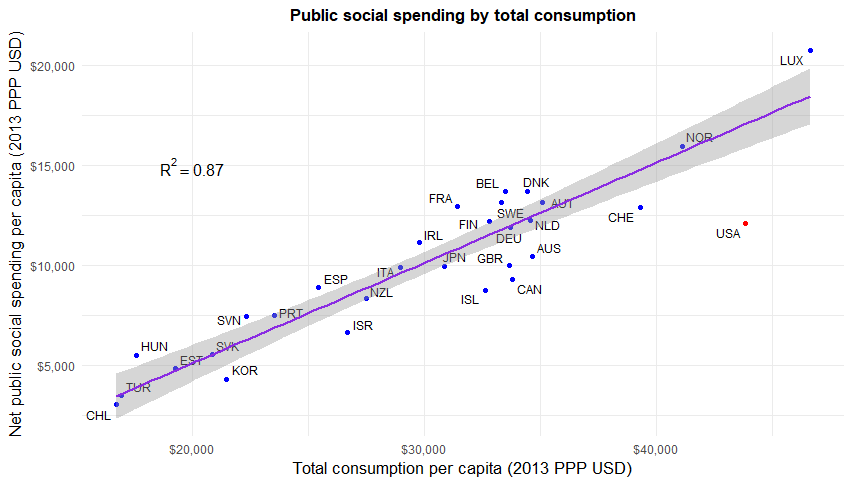

To get the full picture, we can plot public social spending by total consumption directly:

We see here that, in 2013, the U.S. was under-spending on social welfare by about $5,000 per person. Multiplied out by the population, that is about $1.6 trillion. That is, again, for a single year, and it is in 2013 dollars. Unless things have taken a dramatic turn for the better in the intervening five years, the total per-year dollar amount by which the U.S. in under-spending on social welfare is going to currently be more than $1.6 trillion.

Education: an example of under-spending

Matt Bruenig has previously demonstrated how the U.S. under-spends on families with young children, and how this results in massive levels of poverty for these children. Examining each individual area in which the U.S. under-spendings is beyond the scope of this post, but suffice it to say that there is not one particular area where the U.S. is under-spending; rather, it is doing so in all areas.

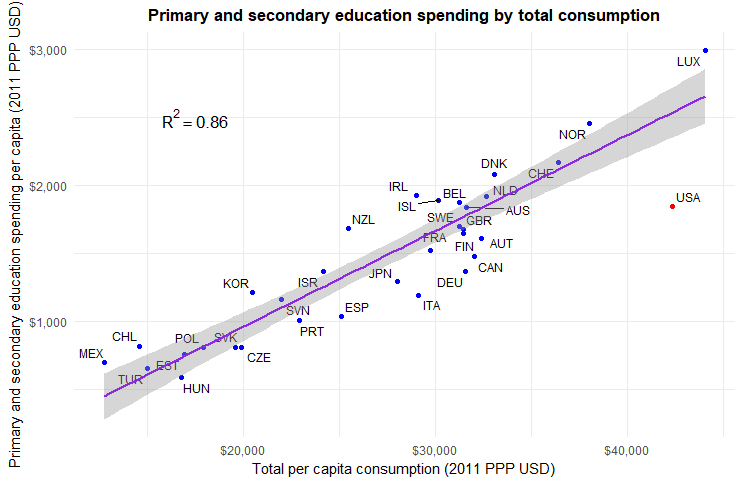

Since this analysis adds education spending to the OECD social expenditure database, we can look at this more specifically, both as a matter of transparency, and as a good example of U.S. under-spending. First, K-12 education:

This looks very similar to the graph showing the full picture of social-welfare spending. Most countries hug the trend line, with the U.S. sitting off in the cold, on its own. We see that the U.S. is under spending on K-12 education by about $500 per capita. This is why we get teachers’ strikes, and frozen pipes in schools, and, ultimately, a lot of kids, particularly kids living in poorer neighborhoods, getting “left behind.”

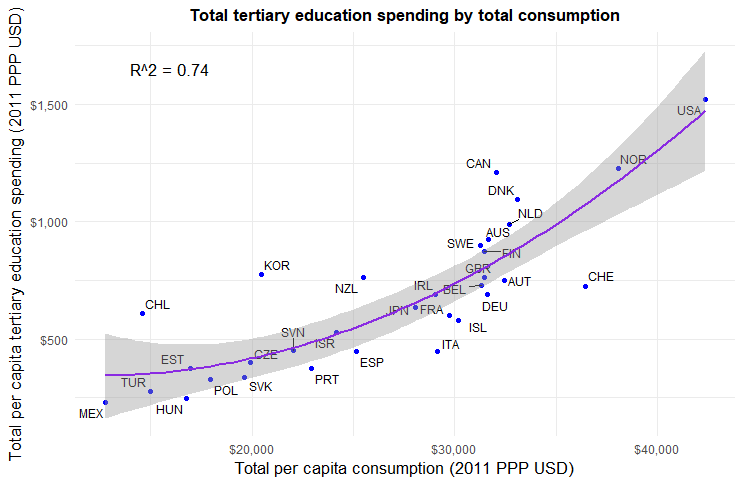

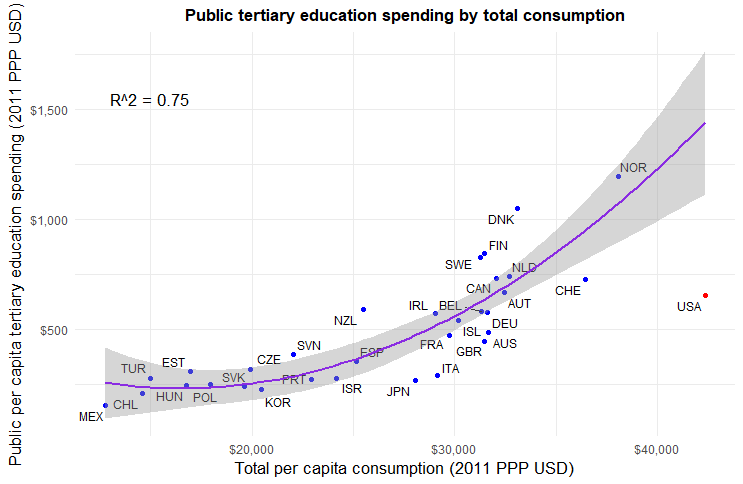

When it comes to college spending, the U.S. is actually right on trend:

But when we look at public college spending, we get quite a different story:

Or rather, we get the same story that we’ve been getting all along: the U.S. spends far too little. Of course, this leads to outrageous levels of student debt, which makes it difficult for young people to make their way in America.

What’s going on with healthcare?

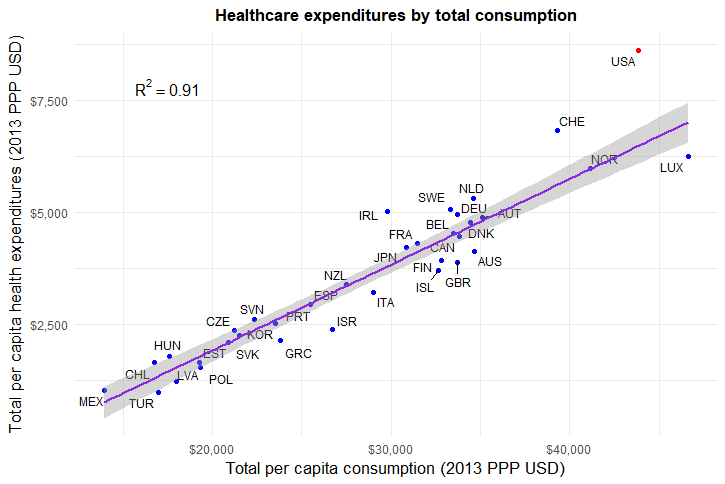

As everyone knows, healthcare is one area in which the U.S. dramatically overspends:

This works out to close to $2,500 per capita of overspending — without, again, even the benefit of universal coverage. So what is going on? If the U.S. spent more in public funds, wouldn’t this put it even further above trend?

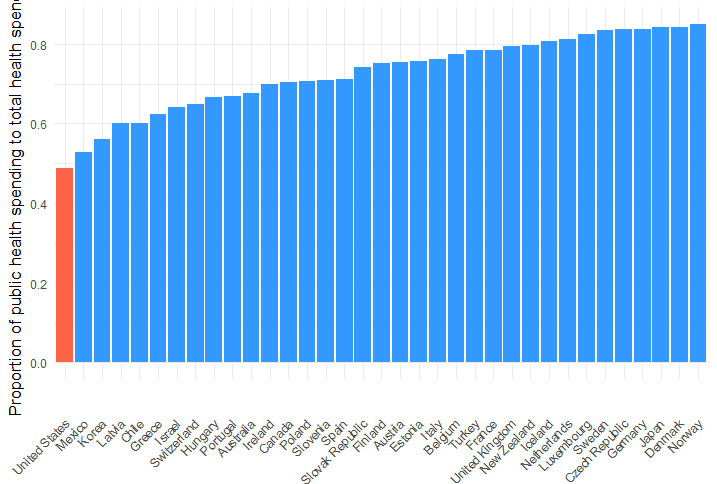

To start, let’s look at the proportion of public healthcare spending to total healthcare spending:

We see that, although the U.S. spends more per capita on healthcare than any other country, it spends proportionally less in public funds than any other country. Might there be a relationship between these two facts? Logically, yes. We know that the U.S. wastes a tremendous amount of money in administrative costs by having a patchwork of private and public insurers all independently negotiating with providers and having their own systems of reimbursement. We also can figure that, with more public funds at state, governments will exert more pressure to keep costs low.

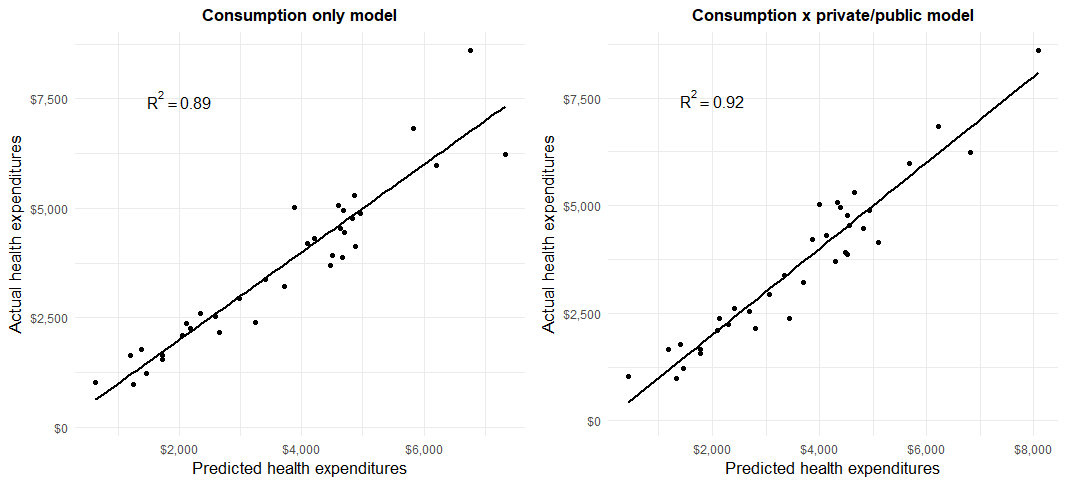

Statistical analysis supports the logical one. Here, I create a model with the ratio of private to public spending as an interaction term to total consumption. Above, I did a regression with consumption as the only predictor for healthcare spending; here, I do a regression with the interaction between consumption and private:public ratio as a predictor.

The interaction term yields a statistically significant effect (p>0.05). We can compare this model to the original model by plotting what each model predicts healthcare spending will be versus what healthcare spending actually is:

We see that, again, total consumption by itself is a very good predictor of health expenditures, so there is not an awful lot of room to improve the model by just adding another variable. However, when we add in the proportion of private spending, we do see an improvement. In particular, it draws in the countries that were furthest away from the trend line (i.e. the U.S., Switzerland, and Luxembourg.)

This is suggestive of the idea that, if the U.S. spent proportionally more public money on healthcare, total costs would drop. This, of course, is exactly what switching to a single-payer system would do, beyond making the distribution of healthcare progressive and universal. As it is, the U.S. has a fundamentally regressive system, where, essentially, most households pay directly for their healthcare costs. The result is that tens of millions go without insurance, and those who do have private insurance end up forgoing a tremendous amount of consumption opportunity in order to pay for it.

Conclusion

It follows fairly obviously from the above that the U.S. should be making large outlays on social welfare that it currently is not making. While other wealthy countries apparently view their inhabitants as part of a society with universal needs, the U.S. largely leaves its people to fend for themselves.

More social spending is not the solution to every problem the U.S. faces. But it would certainly help a significant portion of them.

Technical Note: Why I used total consumption instead of GDP

GDP is a measure of the total economic activity that occurs within the boundaries of a country. There are different formulations for solving GDP. One way to put it is that it is all goods and services consumed by households, plus all goods and services consumed by the government, plus investments, plus net exports.

Actual individual consumption (AIC) consists of all goods and services used by households, regardless of who pays for them. This will encompass everything from hamburgers to a college course on Dostoevksy; a visit to the amusement park, or a visit to the doctor. Again, it does not matter whether the hamburger was paid for with a Social Security check, food stamps, or a portion of a lawyer’s paycheck.

Of GDP and AIC, the OECD says this: “GDP per capita provides an average measure of economic activity … but for comparisons of material well-being of households, actual individual consumption per capita is preferred.”

This is because GDP includes things like income generated in a country that then gets expatriated back to a different country where the parent firm is located. In other words, it can include a lot of money that residents of a country never actually get a chance to appropriate.

Total consumption is AIC plus collective consumption. Collective consumption is whatever the government pays for that isn’t used tangibly by individuals. For example, it will include the administrative costs to run the government and its programs, as well as things like military and police expenditures. We see then that all social spending ultimately occurs in the realm of total consumption, as it all goes either towards AIC or the cost of running government programs. Thus, we have a quite logical basis to narrow GDP down to total consumption when comparing countries by social spending.

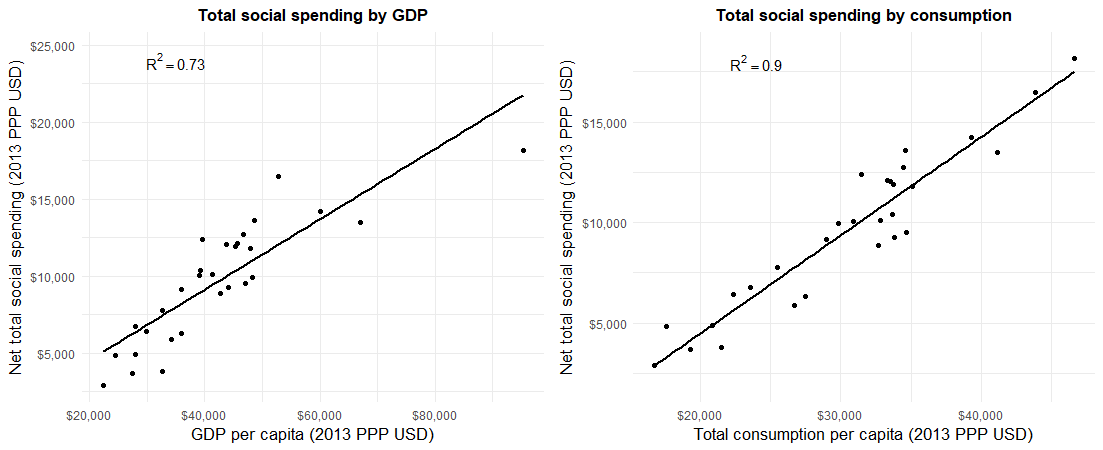

Ultimately, the best reason to use total consumption over GDP as a yardstick here may be that it is a better predictor of social spending. For example, the following set of graphs shows the difference between using GDP (left) as a predictor of total social spending (as the OECD database has it, i.e. public plus private and without education spending) and using total consumption (right) as the predictor:

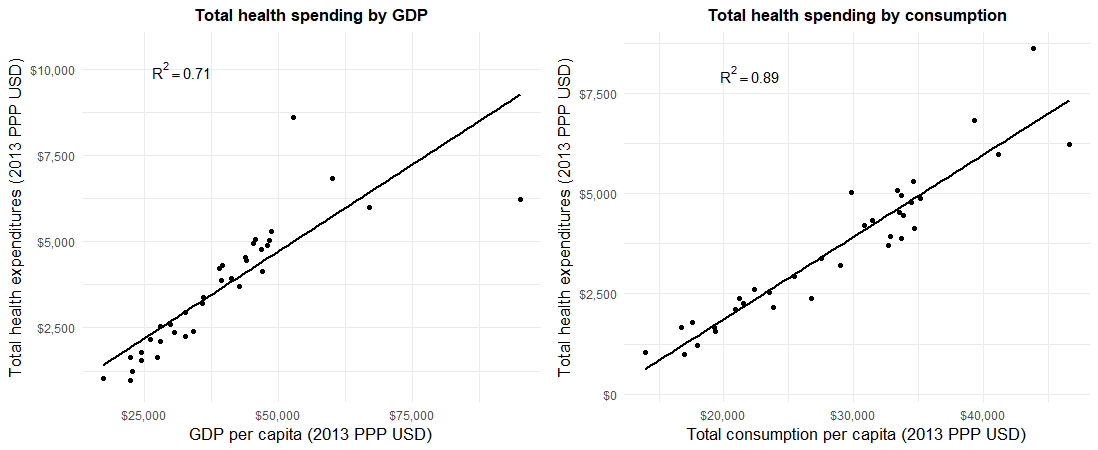

Or here is the comparison using health spending as the outcome variable:

In fact, every single outcome measured in the above analysis is better predicted by total consumption than by GDP, with one exception. The exception is K-12 spending, where GDP is a slightly better predictor if we include the U.S. But even there, once we take the U.S. out of the equation, consumption is once again the better predictor.