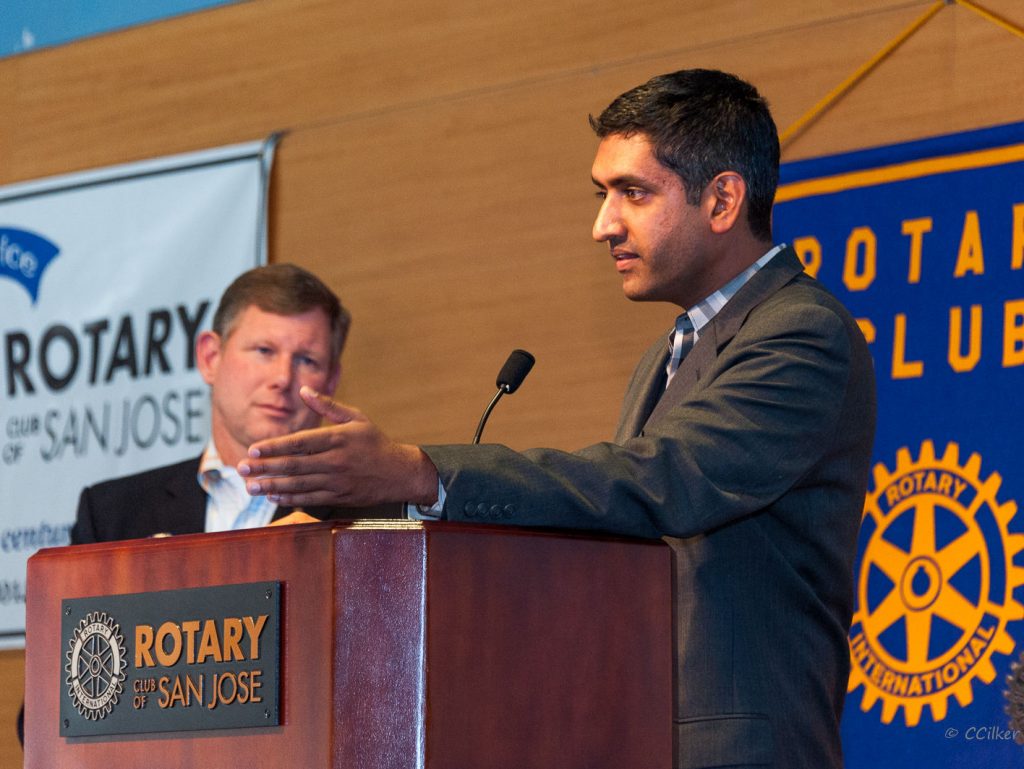

Congressman Ro Khanna is set to release a plan under the new “jobs guarantee” banner that is now simply synonymous with any sort of job-related policy. Connoisseurs of active labor market policies (ALMPs) will notice that Khanna’s plan bears a striking resemblance to programs found in parts of Europe, Denmark in particular.

According to the nascent coverage of the plan, Khanna would provide subsidized jobs to adults over the age of 18 who have been out of work for 9 months or whose earnings fell below the poverty line for at least six months. Employers in all sectors would be able to hire a subsidized worker and job placements would last for 18 months. Various restrictions would also be put in place to prevent employers from abusing the program.

In short, the Khanna plan subsidizes the wages of the long-term unemployed and then uses those subsidies to get them placements in normal workplaces.

Denmark has operated a similar ALMP, with considerable success, since 1980. Here is how the Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment currently describes the program:

Jobs subject to wage subsidy at public or private employers can be used to retrain the professional and social competences of unemployed people. Wage subsidies (both in the private and the public sector) are provided to employers when they hire a person who has been unemployed for at least 6 months. Public and private companies are eligible for a wage subsidy to hire an unemployed person for a period of 4 or 12 months depending on which category of unemployment he or she belongs to.

This sort of ALMP makes a lot of sense for two reasons.

1. Structural Unemployment

People often talk about unemployment as if it is a single thing, but as Josh Bivens explained recently, it’s really three different phenomena.

There is demand-deficient unemployment, which is the unemployment you see in recessions and their aftermath. For that kind of unemployment, fiscal and monetary policy should be able to pump up demand and get people back to work.

There is also frictional unemployment, which describes people who are simply between jobs. For instance, when an employer has to do a layoff due to lagging sales, their ex-workers are temporarily unemployed as they migrate into a new business or sector. For this sort of unemployment, you mostly just want to provide generous unemployment benefits and job search assistance.

Then there is structural unemployment, which describes people who are essentially unemployable in their current state. This might be due to lack of experience or skills. It might also be because they have a criminal record and employers are wary of that. It is this kind of unemployment that really calls for active labor market policies of the type Denmark has and that Khanna is proposing.

Those suffering from structural unemployment find themselves in a Catch-22. They can’t get a job in their current state. But they can’t escape their current state without getting a job (or perhaps training and education). Wage subsidies break through that Catch-22 by making the structurally unemployed more attractive to employers and thereby securing them a job.

2. Normal Jobs

Another charm of the Khanna proposal is that it places the structurally unemployed into normal jobs, whether in the public, private, or non-profit sector. This allows them to add value and gain experience that is not segregated from the rest of the workforce. The latter point is important when it comes to giving the workers a better chance to remain permanently employed in the mainstream labor force.

Other people operating under the JG banner are steadfastly against placing the structurally unemployed in ordinary jobs, but this ends up creating a bizarre mess of an idea. Placing structurally unemployed people into segregated make-work jobs is neither a particularly good way to produce things (especially critical public works and services) nor a particularly good way to help such workers become employable in the mainstream labor force.

In addition to normal jobs helping the workers, it also is a better practice for the economy as a whole. The goal of working is to produce things and so you need to put the workers where the production actually is. Depending on ownership institutions and the level of public provision, that will mean putting them in different places in different societies, but the basic rule remains the same: workers need to be allocated into the productive apparatus of their society.