Yesterday, I wrote a quick post about how we could solve (or at least help) the Social Security “insolvency” problem by having the Federal Reserve give the Social Security Administration a bunch of the Federal Reserve’s Treasury bonds. “Insolvency” is defined purely in terms of when Social Security runs out of Treasury bonds, meaning the plan would work by definition. It’s fun because it’s kind of wacky and makes you realize how silly the way we talk about Social Security insolvency really is.

To my surprise, the LA Times’ Michael Hiltzik took to Twitter to express his extreme dislike of the post.

A real stupid, erroneous, and frivolous take on a topic that demands intelligent coverage. Not a good look for @MattBruenig https://t.co/0npiuPrE6g via @PplPolicyProj

— Michael Hiltzik (@hiltzikm) June 8, 2018

When Hiltzik clarified his precise problems with the piece, the whole thing became even stranger.

1. “Insolvent” Word Game

In his first move, Hiltzik makes two claims: (1) the trustees report does not use the word “insolvent,” and (2) the system won’t be insolvent through the 75-year projection used in the trustees report.

1. Start with paragraph 1: “The headline is that ‘Social Security will become insolvent in 2034.”’ That word isn't in the trustees report, but reflects journalistic laziness. The system isn’t insolvent, and won’t be insolvent through the 75-year projection used by the trustees.

— Michael Hiltzik (@hiltzikm) June 8, 2018

Concerning the first claim, it is literally true that the trustees report does not use the word “insolvent.” But the report does use the word “solvent” 9 times. And it even defines the term in the document:

Solvency. A program is solvent at a point in time if it is able to pay scheduled benefits when due with scheduled financing. For example, the OASDI program is solvent over any period for which the trust funds maintain a positive level of asset reserves.

This is exactly what I wrote in my piece:

So-called Social Security insolvency refers only to the point at which the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) trust fund redeems its last special-issue Treasury bond.

So the trustee report does not use the word “insolvent,” but it does say that the program will stop being solvent once the trust fund runs out of assets. If only there was a word for when something stops being solvent.

Concerning his second claim, Hiltzik is just wrong about what the report says. The report says that the program will be insolvent in 2034, by which it is meant that it will have exhausted its trust fund and not have enough current revenue to cover scheduled benefits.

Subsequent tweets reveal that what Hiltzik is really doing with that second claim is saying that the word “insolvent” should be used to mean literal bankruptcy. And since the SSA will automatically cut benefits to avoid bankruptcy, it can never be “insolvent.” That’s fine if that’s how you want to use that word, but that’s not how the SSA uses that word and, crucially, I actually explain this in my own piece:

If those receipts are too low (i.e. the payroll tax rate is set too low), then benefit checks will be lower than the current benefits formula promises.

It is truly baffling to me why Hiltzik has worked himself up here. If he wants to encourage people to use different words, then that’s fine. But instead he’s buried his own idiosyncratic word choices into an argument about how I am wrong even though I’ve described the “insolvency” stuff accurately.

2. You Forgot Clawbacks

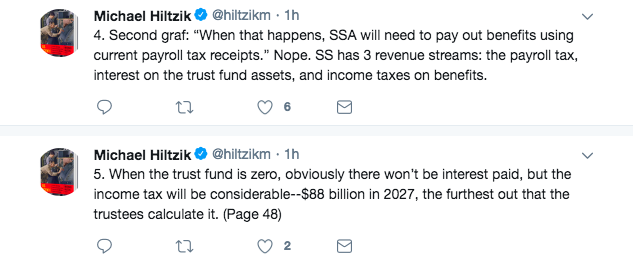

Hiltzik next takes issue with my claim that, after the trust fund runs out, the “SSA will need to pay out benefits using current payroll tax receipts.” Hiltzik’s response is that the SSA will actually pay benefits using current payroll tax receipts and taxes on Social Security benefits.

There are two issues here.

First, “considerable” might be overstating this “revenue source.” The $88 billion in tax clawbacks in 2027 is compared to the $1.383 trillion in payroll tax receipts for that same year. I think one could be forgiven for making a simplification that says the SSA will need to “pay out benefits using current payroll tax receipts” as I did

Second, whether tax clawbacks should be understood as a revenue source or benefit cuts is one of those deep metaphysical questions that people will disagree about. If Hiltzik thinks it is very important to categorize clawbacks as revenue rather than as benefit cuts, then would he be OK passing a new law applying a flat 17 percent tax on all Social Security benefits with the revenue from that tax being earmarked for the Social Security program? This would fix the projected Social Security shortfall without cutting benefits at all!

Once again, I don’t understand how Hiltzik has got himself so worked up here. We’re talking about a tiny “revenue source” that is arguably not even a revenue source at all.

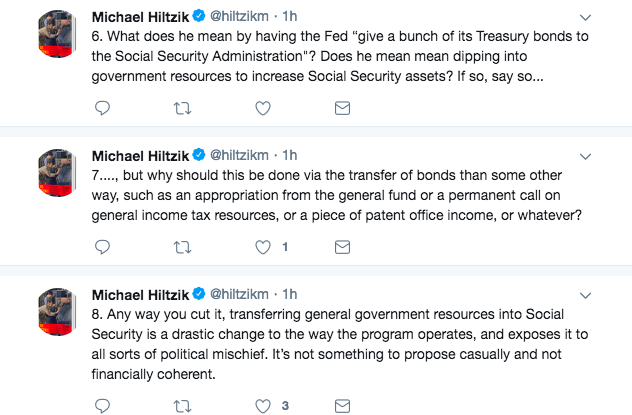

3. Confusion About Solution

The next issue he has is that he says he doesn’t understand what I mean when I say the Federal Reserve should just hand over some of its Treasury bonds to the SSA.

What I mean by this is that the Federal Reserve, which owns $2.4 trillion of Treasury bonds, should give a bunch of those bonds to the SSA. I don’t know how much simpler I can state it than that. It’s sort of like if I owned a bunch of Treasury bonds and then I gave them to you and now you own them.

Why do this instead of other solutions? Because this one is fun as it directly exploits the goofy way that the trust funds work (they are “invested” in Treasury bonds). The other solutions are not nearly as fun, in my opinion.

4. Accounting Gimmicks

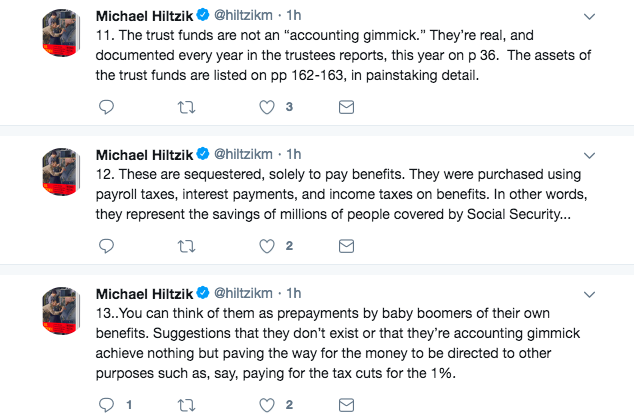

Finally, Hiltzik takes issue with the last sentence of my piece where I say having the Federal Reserve transfer a bunch of Treasury bonds to the SSA “would be an accounting gimmick of sorts, but that is all the SSA trust funds are anyways.”

Hiltzik seems to think that a government borrowing money from itself is not a gimmick provided enough paper and ritual and accounting is layered on top of it. But that does not really respond to the chief reason people say it is a gimmick.

The reason it is a gimmick for the government to borrow from itself in order to “save” is that this does not really change the underlying conditions of how those savings will eventually be redeemed.

What happens when the SSA “redeems” its bonds with the Treasury? The Treasury gives them cash. Where does the Treasury get that cash? From taxes or borrowing from non-SSA creditors. So, in short, the “savings” are redeemed in the future by having the government use taxes and borrowing to spend money.

What happens if the government never had an SSA trust fund but needed to raise money in order to pay out Social Security benefits? Where would it get that cash? From taxes or borrowing. So, in short, future shortfalls under this regime are being covered by using taxes and borrowing to spend money.

It’s the same thing. The trust fund is not doing anything fiscally, though it is doing things legally that possibly make it easier for the program to stay strong even when the government changes hands.

This was the implicit point of my initial post. Insolvency is being defined in weird accounting terms as when the SSA trust funds run out of Treasury bonds. But the reality is that this whole practice is nonsensical because the system of old-age retirement does not depend on internal government assets, but instead on the production of national income and then the distribution of adequate amounts of that income to the elderly so that they don’t have to work.

You could pass a law tomorrow requiring the Treasury to issue $1 quadrillion of free bonds to the SSA trust funds. That would permanently eliminate “insolvency” so defined, but it would not really fix anything.