A lot of people have been sounding off about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) lately.

Doug Henwood in Jacobin:

That fantasy [that money creation can fund the left’s agenda] looks like a weak response to decades of anti-tax mania coming from the Right, which has left many liberals looking for an easy way out. It would be sad to see the socialist left, which looks stronger than it has in decades, fall for this snake oil. It’s a phantasm, a late-imperial fever dream, not a serious economic policy.

Jonathan Portes in Prospect:

MMT is in many respects not wrong: instead, it is a mixture of the tautological, the obvious and the tendentious. But one thing is absolutely certain. The claim that that MMT means that a future government can dodge hard choices about how to pay for decent public services is just plain nonsense.

Max Sawicky in In These Times:

A story that appears to emphasize unlimited public spending, besides being fallacious, will impress most people as either crankish or arcane. It isn’t accepted by a wide spectrum of left-of-center, non-MMT thinkers. Any existing progressive government that comes to power under such delusions is bound to disappoint its constituents. By means of increased public debt, we can expand public spending. In fact, we must. At the end of the day, however, a politically evasive monetary theory should not be the basis for a progressive movement.

Josh Barro in New York:

The government is not constrained by its ability to obtain dollars, but the economy is constrained by real limits on productive capacity. If the government prints and spends money when the economy is at or near full employment, MMT counsels (correctly) that this will lead to inflation, and prescribes deficit-reducing tax increases to reduce aggregate demand and thereby control inflation. See how we have ended up back where we started? Whether you take a Keynesian view or an MMT view, if the government spends more, it’s likely going to need to tax more, sooner or later.

Arjun Jayadev and JW Mason in INET:

While MMT’s policy proposals are unorthodox, the analysis underlying them is entirely orthodox. A central bank able to control domestic interest rates is a sufficient condition to allow a government to freely pursue countercyclical fiscal policy with no danger of a runaway increase in the debt ratio. The difference between MMT and orthodox policy can be thought of as a different assignment of the two instruments of fiscal position and interest rate to the two targets of price stability and debt stability. As such, the debate between them hinges not on any fundamental difference of analysis, but rather on different practical judgements—in particular what kinds of errors are most likely from policymakers.

As far as I know, I have only ever written about MMT one time way back in 2013 after first hearing about it. Interestingly, my 2013 piece hits upon some of the same points made in the articles quoted above, and ends by pondering whether MMT is really just a very roundabout way of arguing that we should manage the price level through the fiscal authority and the debt level through the monetary authority rather than the other way around. Jayadev and Mason say this is exactly what MMT is about, but, as with most things MMT, it is hard to find a canonical declaration to this effect.

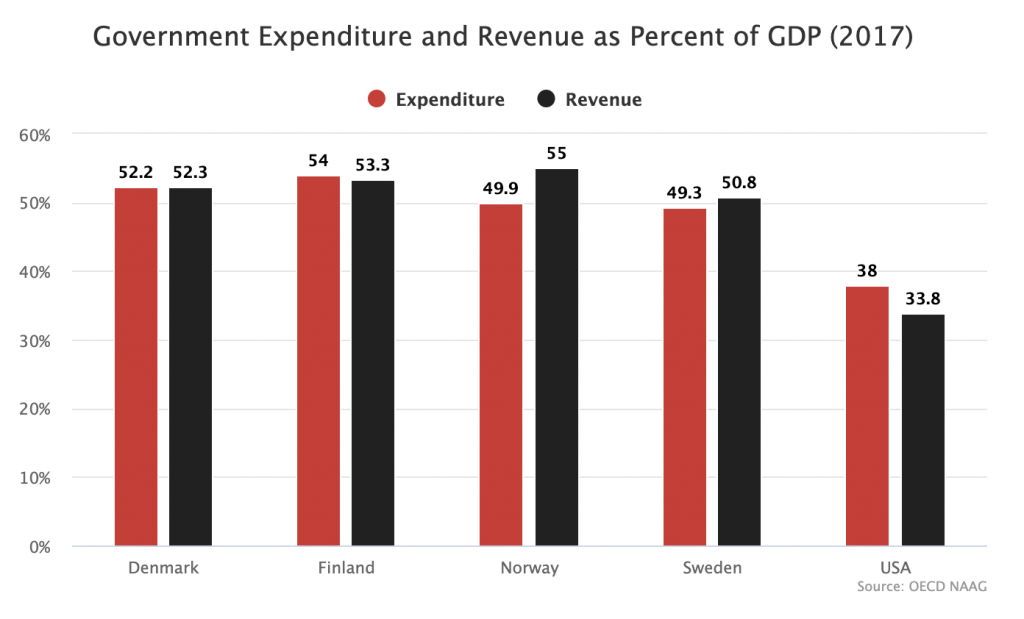

In the six years after my 2013 post, it has become clear to me that the bulk of MMT discourse is not really about what the best policy instruments are for maintaining price stability and debt stability, but rather about using word games to make people believe that the US can have Northern European levels of government spending without Northern European levels of taxation.

To understand how the word games work, it is helpful to start with a description of the way economically-minded people normally talk about government spending. What normal people say is that for the government to spend, it needs to get money. And it can get money from three sources:

- Taxes.

- Borrowing.

- Money creation.

The usual description then says that after getting cash from one of these sources, the government can spend it on government consumption and investment or transfer it to someone else via the welfare state. In the case of taxes and borrowing, money comes into the government and then is spent back out. In the case of money creation, the government originates new money and then spends it out.

What MMT advocates do is assert that actually all government spending is funded by money creation. Taxes and borrowing may look like ways the government gets cash to spend, but in fact all they do is delete money. Why would you ever want to delete money? Because, when the economy is at or near capacity, creating a bunch of new money and spending it into the economy will cause inflation. Thus, you need to use taxes and borrowing to delete the new money and avoid inflation. Understood this way, all government spending is financed by money creation, and taxation and borrowing exist only to offset the inflation caused by that spending.

By itself, this rhetorical effort to recategorize things is fine, if a bit tedious. As many commentators have noted, this is what Abba Lerner also said.

But what they do next is use their idiosyncratic categories to say things that are true under their definitions but confuse people who are not familiar with the private language of MMT.

So they will say things like “taxes don’t fund spending” or things like “the answer to how will you pay for it is simply that you will spend the money” in discussions about, for instance, how to do welfare state expansions. Many people on the left read this and believe them to be saying that we can have a Nordic-style welfare state without increasing the US tax level. After all, if taxes don’t fund spending, then we don’t need them, right?

But that is not what they are saying. If you understand the MMT private language or have a couple of hours available to talk to an MMT advocate and slowly peel back the layers of obfuscation they like to use, you realize that “taxes don’t fund spending” is not saying we don’t need to raise taxes to expand the welfare state. Rather, it is saying that, in their idiosyncratic way of categorizing things, the necessary taxes do not “fund the welfare state,” but merely “offset the inflation caused by the money creation that funds the welfare state.”

This is a good way to jam up the discourse and confuse people, which can arguably be useful politically, but as a policy matter, it does not add any new insight. It tells you that the correct question is not “how will you pay for this” but rather “how will you offset the inflation that is caused by paying for this with created money since all government spending is created money.” Nonetheless the rephrased question has the same answer as the first one: some combination of taxes and borrowing that will eventually have to be worked out.

If the point of MMT is really about how it would be better to have the fiscal authority manage the price level and the monetary authority manage the debt level — as I thought it might be in 2013 and as Jayadev and Mason argue it is — then you would expect to see a lot more discussion about the competencies and flexibilities of each authority at those tasks. But there is surprisingly little written about such things in these circles.

The real point of MMT seems to be to deploy misleading rhetoric with the goal of deceiving people about the necessity of taxes in a social democratic system. If successful, these word games might loosen up fiscal and monetary policy a bit in the short term. But insofar as getting government spending permanently up to 50 percent of GDP really will require substantially more taxes in the medium and long term, I have to agree with Sawicky and Henwood in saying that MMT seems like a political dead end.