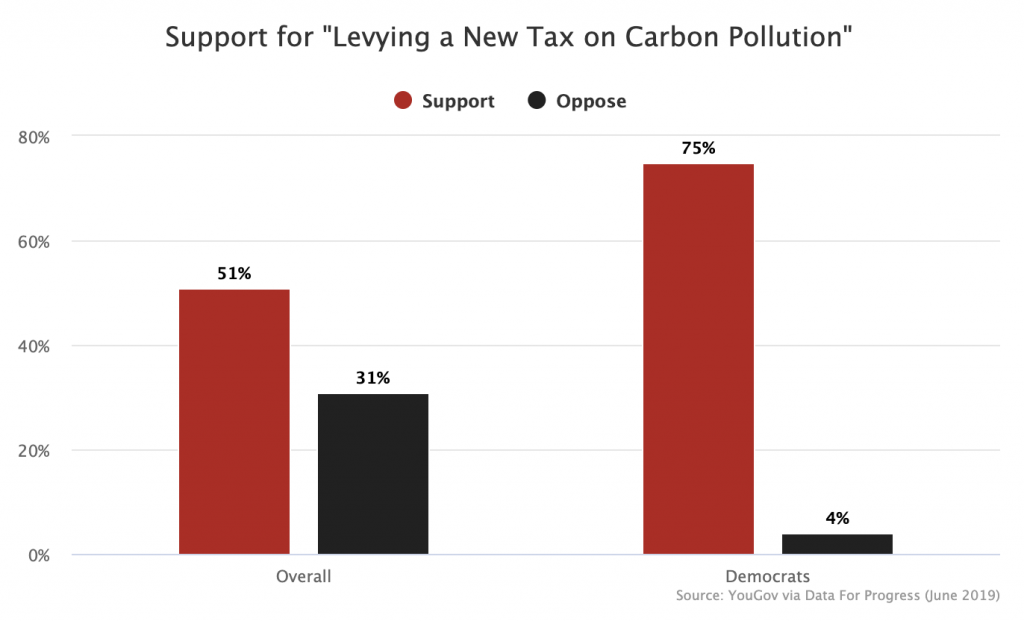

Earlier this year, Data For Progress released polling data from YouGov that showed that carbon taxes are popular among the general public and enormously popular among Democrats.

Indeed, the overall level of support for a carbon tax is identical to the level of support for a job guarantee, which DFP describes as a margin that is “nothing short of stunning.”

What was especially remarkable about DFP’s result is that they asked the question in a somewhat negative manner. They used the word “tax” rather than “fee” or “charge” or “fine” as others use. And they don’t say anything about where the revenue from the tax is going. Yet despite that, the support they found was massive.

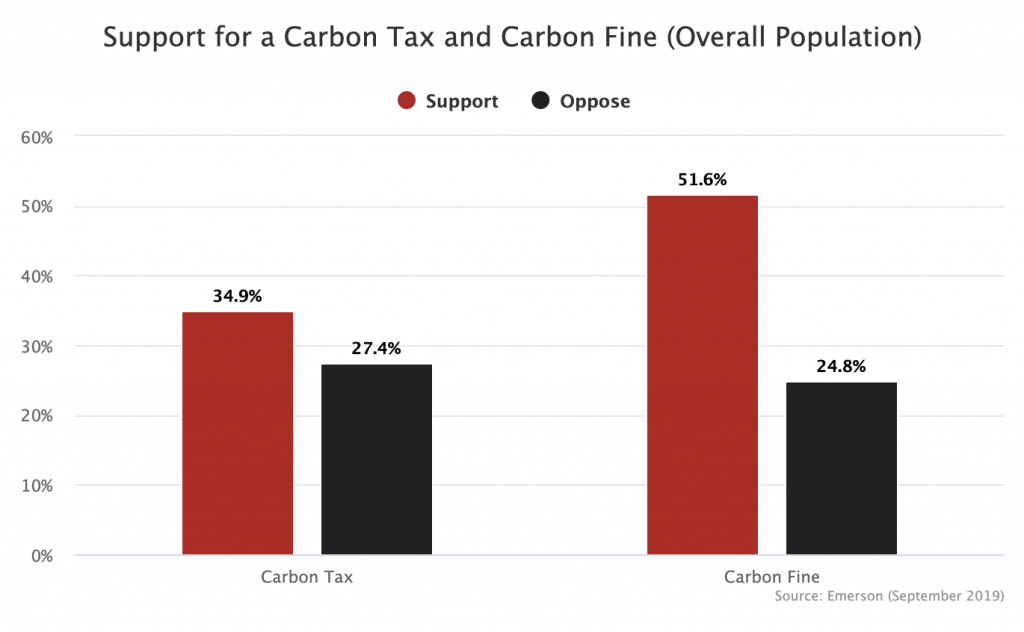

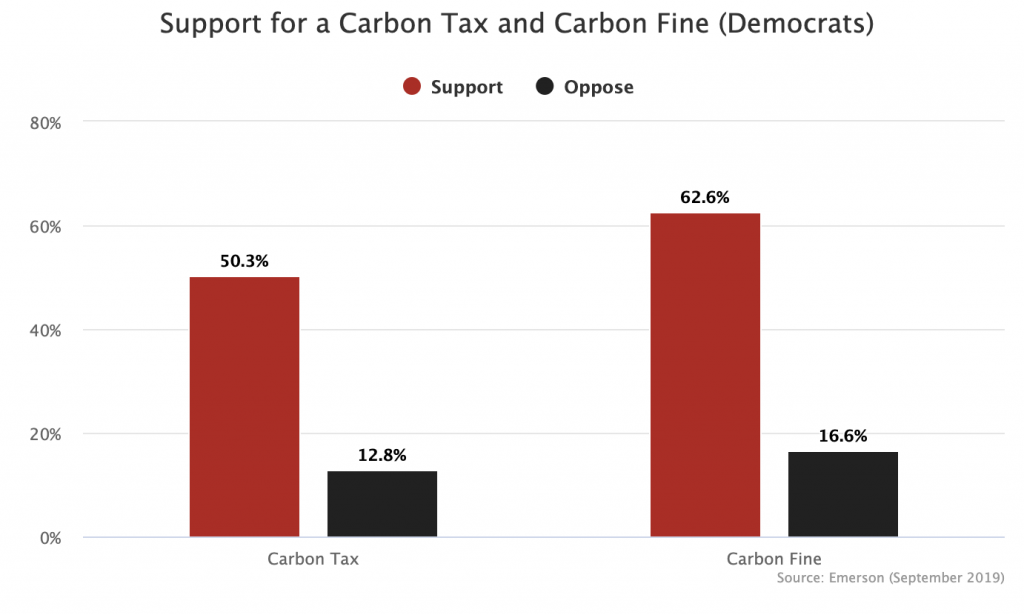

After reading their work, I was curious what the results would look like if you described this sort of policy in a more positive way that is still nevertheless completely accurate. Luckily, Emerson polling did just this in a poll released earlier this month. In that poll, they split the sample and asked half of them “Would you support or oppose a carbon tax?” while asking the other half “Would you support or oppose a fine on corporations that pollute the air with carbon dioxide?”

As expected, the “carbon fine” question did much better than the “carbon tax” question, but both did well.

The Emerson results are not directly comparable to the YouGov results because Emerson asks people only if they “support” it, “oppose” it, or are unsure, while YouGov gives people the additional options of “somewhat support” it and “somewhat oppose” it. Allowing the “somewhats” in gets you fewer unsure responses and so the overall numbers are higher.

Nonetheless, the Emerson figures show us that a “carbon fine” does better than a “carbon tax,” meaning that even DFP’s astonishingly good findings understate just how high those numbers could be driven if the program was described in a more positive (but still accurate) way. The Emerson poll also did not say anything about how the money is being spent, which suggests to me that the numbers could be even higher if you brought that part in.

Recently, more conservatively-minded Democrats have begun saying that we should not pursue carbon charges, arguing that we should allow the open market to set the price of carbon rather than having the central government dictate prices from on high. But what these polls show is that this argument falls flat, at least as it concerns public opinion. The public is ready to have the government set carbon prices in a Soviet manner in order to help fight climate change.