When coronavirus relief bills were being discussed a couple of months ago, I proposed the following non-exhaustive scheme:

- Paid Leave. Create a one-month sickness allowance for those who need to take leave from work because they contracted the virus. Create a family leave benefit for those who need to take leave from work because they need to take care of family, e.g. due to school closures.

- Unemployment Insurance. Expand unemployment benefits by replacing 100 percent of prior earnings up to $8,333 per month and by providing a minimum unemployment benefit, including to those not traditionally eligible for such benefits, of $1,063 per month.

- Universal Payment. Pay $1,000 per month to every person for the duration of the crisis.

- Corporations. Bail out companies that need help in exchange for equity. Set aside a large pot of money to buy publicly-traded equities more generally.

The response we actually got was similarly patterned, but different in its particulars. Below I summarize that response and provide some commentary on its effectiveness.

Paid Leave: Mandate and Refundable Tax Credit

A temporary paid leave mandate was established by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Under that mandate, employers with 50 to 499 employees have to provide up to two weeks of paid leave to an individual who has coronavirus symptoms, has been told to quarantine due to coronavirus, or is caring for someone quarantined due to coronavirus. The mandate also provides up to 12 weeks of paid leave to parents who have to miss work due to school and child care center closures. Employers who provide paid leave are made whole by the government through a refundable tax credit.

The limitation of this program to employers with 50 to 499 employees set off a wave of media backlash because it made no sense. The small business exemption puts the interests of small business owners over the interests of their workers, which is typical in American policy. It also exempts the large share of workers employed by franchise companies like McDonalds because each small franchise is considered its own firm. The big business exemption excluded the even larger share of workers employed by companies like Amazon or Walmart. All together, only 25 percent of private sector workers are employed in the 50-to-499 employee firms covered by the mandate.

Congressional leaders tried to defend this move by saying that they think big employers should already be providing paid leave. But this also made no sense: if big employers should already be providing paid leave, then including them in the mandate should be no problem. If the goal was to prevent big employers from claiming the refundable tax credits, then that could have been achieved by subjecting them to the mandate but excluding them from the tax credits.

Upon reflection, it seems like this scheme has mostly been a failure. It excluded 75 percent of private sector workers from the beginning. A large share of the remaining 25 percent are probably unaware of the program or uncertain whether their firm is even covered by it. Even in cases where workers are aware of the law and confident that they qualify, many of the covered firms are probably illegally denying paid leave requests. Workers in that situation could file a wage-and-hour lawsuit to vindicate their rights, but very few are probably willing to do that.

Unemployment Insurance: Superdole and PPP

The coronavirus caused many businesses to lose a bunch of customers and revenue, which meant that those businesses needed many fewer workers than before. Broadly speaking, there are two things you could do for these idled workers:

- Move them onto unemployment benefits funded by the government.

- Keep them on payrolls but have the government fund the payrolls.

There was a lot of heat in the discourse about which of these two options was the best solution and even more heat about how to understand the ideological valence of each. To my mind, they are basically the same thing even though the national accounts treat them very differently, with the first option registering as Great Depression levels of unemployment and the second option registering as the biggest corporate giveaway in history.

The CARES Act ended up taking both approaches.

It increased unemployment benefits by adding $600 per week to what recipients would normally receive from the program, extended the duration of unemployment benefits by 13 weeks, and expanded eligibility to individuals who are not typically covered by the program, such as independent contractors. The latter change, which is called Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), appears to have only been implemented by 23 states as of May 2.

It also created the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which allowed businesses with fewer than 500 employees and hospitality businesses of any size to apply for a loan equal to 2.5 months of their ordinary payroll expenses. Those loans are then forgiven if at least 75 percent of the loan amount is used on payroll expenses and the remainder is used on utilities, rent, or mortgage interest. Loan forgiveness is also subject to a separate rule that reduces the amount that can be forgiven proportional to a firm’s reduction in workforce size, e.g. a firm that uses their money solely in approved ways but also laid off 50 percent of their workers would only have 50 percent of their loan forgiven.

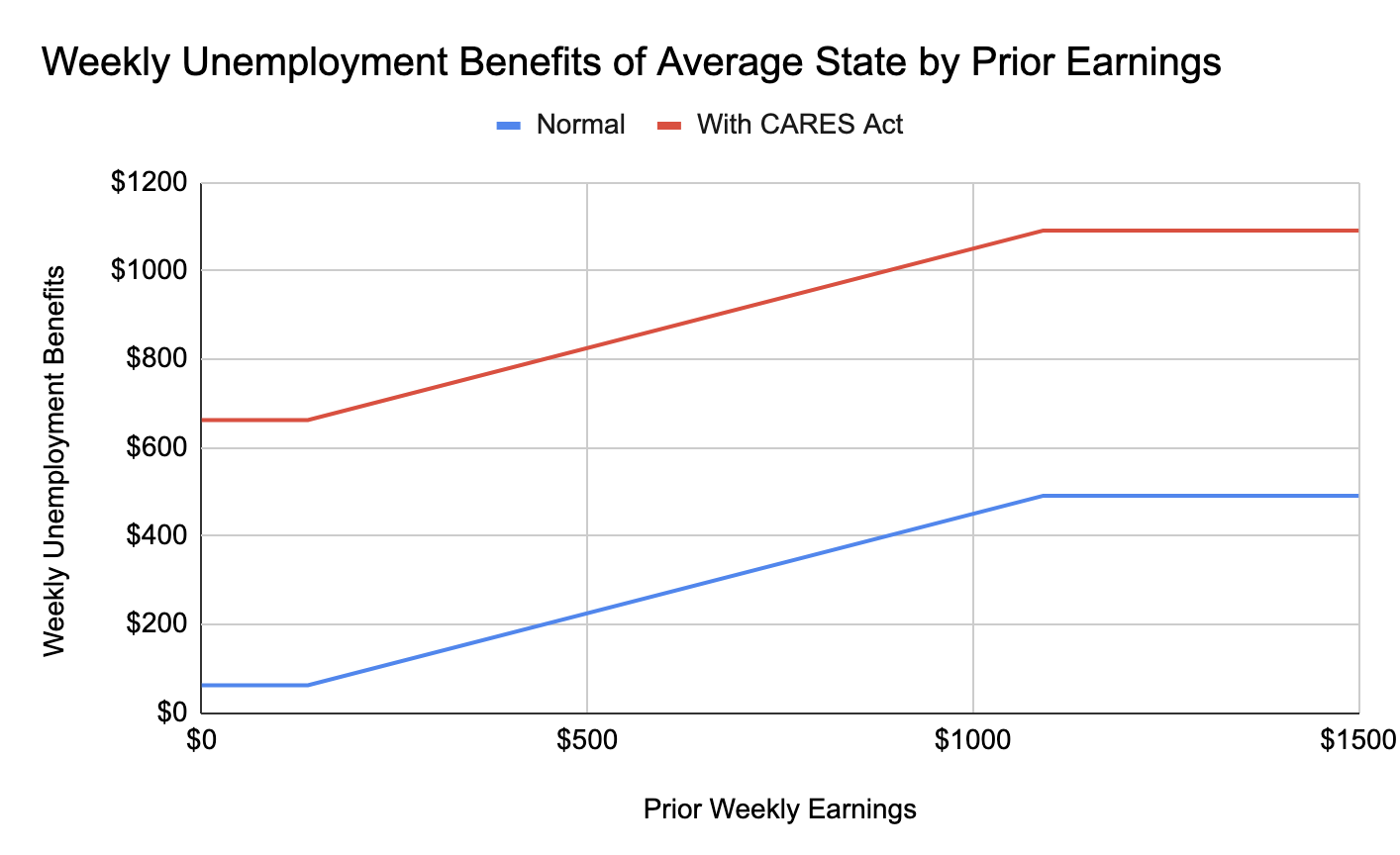

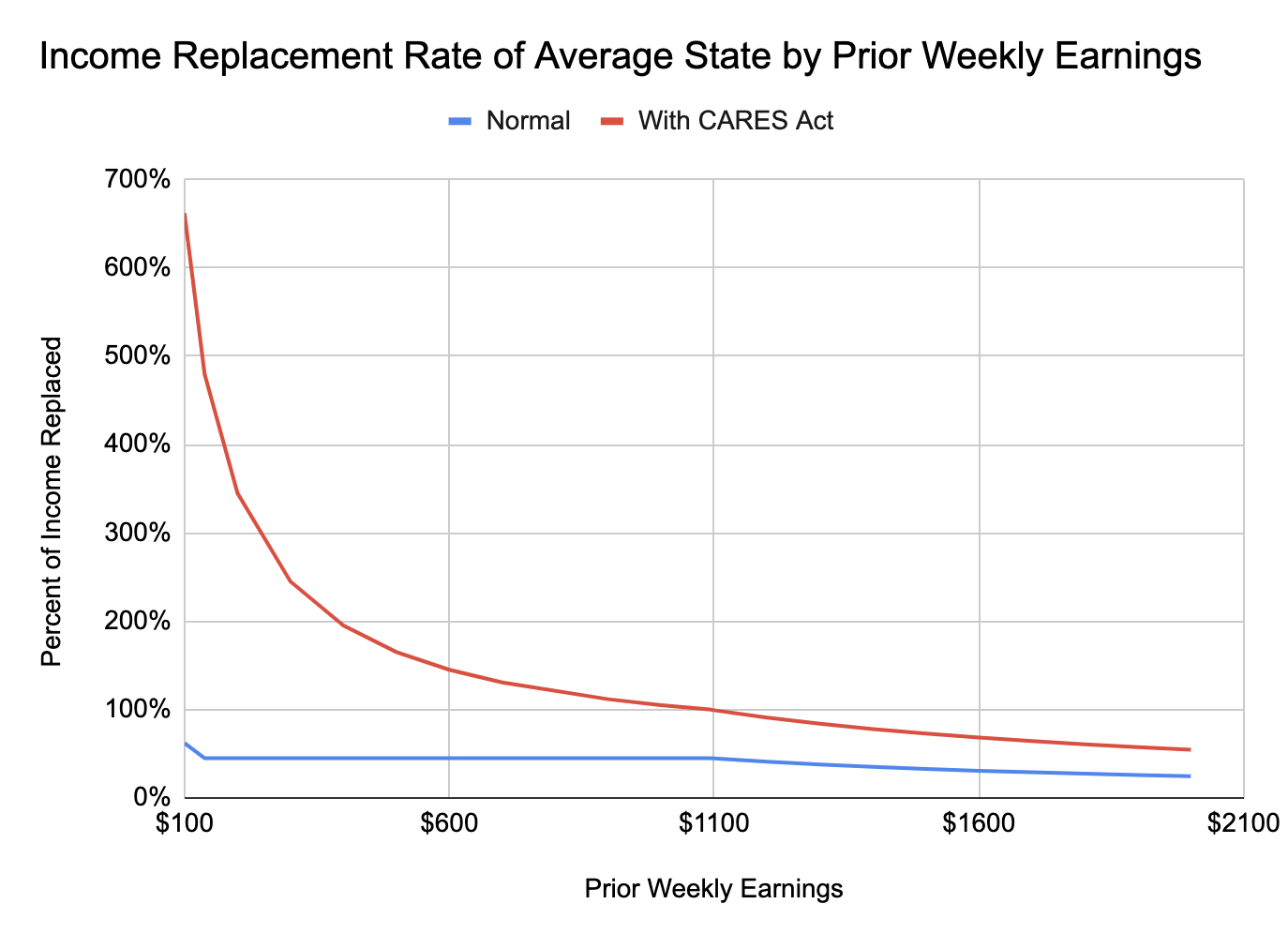

If you take the unemployment benefit parameters of the average US state and add the $600 bonus payment to them, you get the following graphs:

The high income-replacement rate for low-to-moderate earners has caused some media backlash, some unfair asymmetries between workers in different sectors, and some bizarre interactions with PPP.

The media backlash is mostly misguided conservative angst about the general idea of someone receiving more on benefits than they received while they were working. This angst is unwarranted in general and even more unwarranted in the present scenario where labor supply (i.e. people trying to find work) is not needed. In fact, the opposite is needed because we want people to stay home if they can.

The asymmetries between workers is troubling but appears to be the best we can do. It does not make sense that a laid off restaurant worker has their income double while an identically-paid grocery store worker who stays on the job does not. An ideal design would have replaced all of the restaurant worker’s income and then provided both the restaurant worker and grocery worker a universal bonus payment. But for technological reasons, the unemployment benefit systems could not be quickly transitioned to a full-replacement formula. They could only add a fixed sum of money quickly. And so the $600 bonus payment, which along with ordinary benefits ensures full replacement or better up to the average US wage, was the most reasonable thing to do.

The bizarre PPP interactions were bad and could have been avoided if the PPP were better designed. In order to receive forgiveness for a PPP loan, a business owner has to maintain the same workforce size it had prior to the coronavirus. But, for most workers, it would be better if they were let go and put on the unemployment superdole instead. Indeed, many had already been laid off before the businesses received the loans, which meant that in order to get forgiveness, the businesses had to try to rehire them off of unemployment benefits, which would have cut their incomes.

This rule requiring businesses to maintain the size of their workforce was a total mess and should have never been included. Instead, businesses should have been able to get the loan to cover whatever payroll expenses, utilities, rent, and mortgage interest they still had even if they had also laid off a large share of their workforce onto the unemployment system. This PPP rule, when paired with UI expansion, made it so that businesses with lower and moderate wage workers could not really benefit from PPP, ensuring that therefore most of the benefits would likely flow to higher-wage employers and especially employers who did not actually “need” the loan in the sense that their business had suffered.

Ultimately, the unemployment benefit expansions, though weird for technological reasons, were the best thing in the CARES Act package. And as antiquated as our UI computer systems are in the US, we have nonetheless managed to put 22 million people onto the UI roles as of April 25, up from 1.6 million people in the same week of the prior year.

Universal Payment: One Time $1,200/$500

The CARES Act instructed the IRS to pay $1,200 to every non-dependent adult and $500 to every child up to a certain income limit. To facilitate these payments, the IRS used information from prior tax returns and also created a website where people could input their own payment information. This program was a bit of a mess because a large share of eligible people do not have direct deposit information on file with the IRS and some don’t even have addresses or their addresses have changed.

It’s perhaps a bit early to figure out exactly how well the universal payment was executed, but given the inherent difficulty of getting the money out to people with the information that was available, it seems to have gone as well as could be expected.

As a matter of design, a one-off universal payment was a mistake. Instead the payment should have been monthly until the end of the crisis.

Corporations: Bailout Loan Slush Fund

In addition to PPP, the CARES Act put aside a huge chunk of money for the Treasury to use to provide loans to ailing firms. The use of loans instead of equity purchases was a mistake, though a loan is better than a grant, since at least the Treasury will get something back from it. It seems to be too early to say what will come of this bailout slush fund, but I do not have high hopes.