The plight of the unemployed is an important topic for leftists in the US. But the left often fails to think about the unemployment system as a whole, which leaves us with a hodgepodge of proposals that often don’t make sense either individually or within an overall scheme. In this post, I hope to lay out the basics of how to think about the unemployment system in order to provide a framework for making unemployment system design choices.

Administration

The first question is: who should administer an unemployment benefit system? Three common options are:

- National government. In the US, this would most likely mean having the Social Security Administration execute the program.

- Subnational governments. The US currently uses this option as unemployment benefits are administered by state governments.

- Unemployment funds. Under this option, non-governmental entities (often unions) administer benefits. This is a common approach in Northern Europe though the national government is also heavily involved in the funding and administration of benefits there.

In general, I think it’s safe to say that the US has had a bad experience with using subnational governments to administer welfare programs. SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and even UI have been badly mishandled by states, which frequently enact onerous work and paperwork requirements to make it harder to receive benefits, cut benefit levels, loot program funding for inappropriate uses, and refuse to expand the benefits to more people even when it is very cheap to do so.

Given these problems and the fact that we have no real history with unemployment funds, I think it’s clear that we should want the national government, through the Social Security Administration, to administer unemployment benefits in the US.

Eligibility

The second question is: who should be eligible for unemployment benefits? There are two main approaches to this question:

- All out-of-work labor market participants. Under this approach, anyone who is jobseeking qualifies, including individuals who have never had a job or who have been out of the labor market for a long period of time.

- Out-of-work labor market participants with a sufficient work record. Under this approach, a jobseeker only qualifies if they recently separated from a job after being at that job for a sufficient amount of time. US rules are complicated and varied, but a typical rule is that someone needs to have earned above a certain amount in two of the last four quarters.

For the left, the inclusion of all out-of-work labor market participants is a no-brainer. Everyone deserves an income and unemployment benefits are the best way to reach working-age, able-bodied people who are not students or on paid leave of some sort. Along with centralizing the administration of the program under the Social Security Administration, expanding the eligibility criteria in this way should be a major priority for reforming the unemployment system.

Benefit Structure

The third question is: how should the benefit be structured? The three general approaches are:

- Flat payment. Under this approach, all eligible unemployed people receive the same dollar amount for every day that they are unemployed, regardless of how high or low their wage was at their prior job. This is approximately how Australia’s JobSeeker Payment is structured.

- Earnings-related payment. Under this structure, eligible unemployed people receive a dollar amount that is calculated as a percentage of their prior earnings level, e.g. 70 percent of their prior wage up to some cap.

- Payment with flat and earnings-related components. This approach is a hybrid of the first two. Eligible unemployed people receive a dollar amount calculated as a percentage of their prior earnings level, but never an amount below the separately-established flat dollar amount.

Insofar as the earnings-related payment option is incompatible with ensuring that all out-of-work labor market participants receive a benefit, it should be ruled out. Between the remaining options, there is some debate about which one should be preferred by the left.

Advocates of flat payments say that they should be preferred because they do not provide more to (previously) high earners than to (previously) low earners. In that sense, they are more egalitarian than payments with earnings-related components because those payments necessarily mirror the underlying wage inequality to some degree.

Advocates of including an earnings-related component argue that the purpose of the benefit is to provide income security and the only way to provide that to everyone universally is to include an earnings-related component in the payment. On this view, insofar as wage inequality is bad, it should be tackled at the source, not through degrading income security for high-earners. These advocates also argue that flat payment schemes will result in higher-earning people acquiring private unemployment insurance, meaning that they still receive the same benefits, but now in a two-tier system in which they have less connection to the public scheme.

I find the arguments for a payment with flat and earnings-related components the most compelling. This is how the system is structured in Finland and, technically, how it is structured in the US. I say “technically” because, in normal times, the flat component in the US system is so low — less than $20 per week in some states — that it does not really exist for all practical purposes.

Benefit Level

Unlike administration, eligibility, and benefit structure, it is hard to list a number of categorical options when it comes to benefit levels. It is impossible to avoid some arbitrariness when it comes to selecting a flat payment amount or a precise earnings-related formula.

In broad terms, I think it is clear that, in normal times, the flat payment should, along with the rest of the welfare state, be sufficient to meet your basic needs but not so high that it significantly exceeds what you believe the lowest wage in the economy should be. The earnings-related formula should be generous enough that most workers are able to avoid a severe income decline in unemployment.

Activation Requirements

The last big question is: what activation requirements should be imposed on individuals receiving unemployment benefits? Activation requirements, which refers to various activities that unemployed people must do to retain their benefits, do not fit into a simple categorical scheme, but we can imagine four rough approaches:

- No activation requirements. In this scenario, an out-of-work person who self-certifies that they are jobseeking will continue to receive benefits with no questions asked.

- Moderate activation requirements. Under this approach, an out-of-work person will be required to provide some proof that they are jobseeking such as by providing the names of companies that they have applied to in the last week.

- Stricter activation requirements. These requirements include things like attending counseling, training, or education.

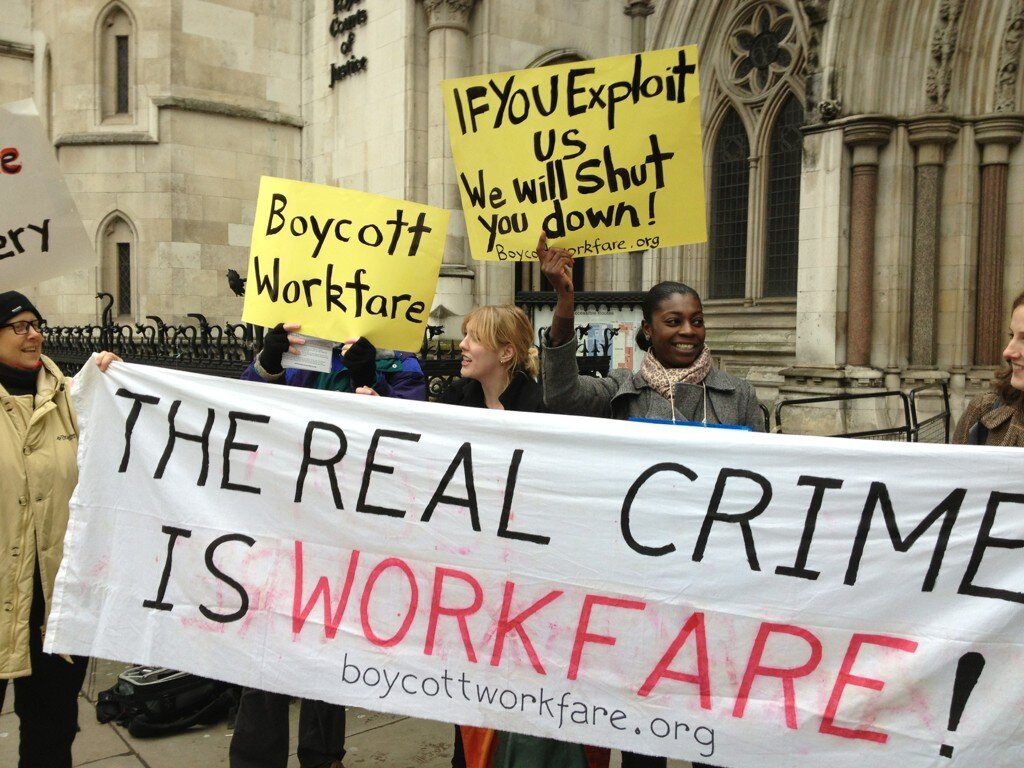

- Workfare requirements. In the workfare approach to unemployment, out-of-work people are required to put in a certain number of hours each week doing tasks assigned to them by the unemployment office.

In general, the left favors no or moderate activation requirements over strict requirements and workfare. This is because activation requirements make life harder on the unemployed, consume time that could be used searching for a job, and result in some unemployed people receiving benefit cuts.

Right now, the US has moderate activation requirements in its unemployment system. Stricter requirements may be seen as unnecessary in a system where the benefit levels are low, the benefit durations are short, and benefit eligibility is restricted only to those who have recently separated from work. In other programs for out-of-work people, much stricter requirements have been imposed, such as in TANF where many states have imposed workfare requirements.

Analysis

When you put it all together, the ideal unemployment system in my view is one that is administered by the national government, is available to all out-of-work labor market participants, is structured as a payment with flat and earnings-related components, and has generous benefit levels with no activation requirements.

Recent proposals to reform the unemployment system have made some improvements in these directions, but have also fallen short of the ideal or even gone backwards in some respects.

The Michael Bennet proposal makes good strides in the areas of increasing benefit levels and expanding the number of out-of-work labor market participants who are eligible. But he fails to establish an adequate minimum benefit, fails to include all out-of-work labor market participants, and continues to administer unemployment benefits on the state level.

The Levy Institute Job Guarantee proposal makes good strides in the areas of establishing an adequate minimum benefit and in including all out-of-work labor market participants. But it fails to improve the earnings-related components of the unemployment system, shifts benefit administration to an even lower level of the government, and uses much more onerous workfare activation requirements.

The Job Guarantee is also a major step back from recent progressive ideas about the unemployment system and income security in particular. The long-standing Medicare for All bill (HR 676) provides two years of unemployment benefits equal to 100 percent of prior income up to $100,000 per year for workers displaced during the transition to Medicare for All. These days, you are much more likely to see people arguing that workers displaced by Medicare for All or the Green New Deal should instead receive flat unemployment benefits equal to the minimum wage regardless of how much they used to earn and be required to submit to workfare requirements (the Job Guarantee). This is both bad policy and also likely bad politics.