Back in my Demos days, I wrote a dozen or so pieces about the Success Sequence that have unfortunately been lost to time. When I started People’s Policy Project four years ago, I wrote two (I, II) fresh pieces about it, but abandoned talking about the subject when interest seemed to wane. Last week, Bryan Caplan became the latest victim of the Success Sequence con, giving me an excuse to talk about one of my favorite subjects.

What Is the Success Sequence?

The Success Sequence (SS) is presented as a series of steps individuals can take that will ensure they have a very low poverty rate. Caplan describes the steps as follows:

- Finish high school.

- Get a full-time job once you finish school.

- Get married before you have children.

If you read the SS literature, what you find very quickly is that every person who writes about it has a different definition of it. Caplan cites to Sawhill and Haskins (S&H) and then to Wang and Wilcox (W&W) as if they are both doing research on the same thing. But they aren’t.

To follow the S&H SS, you need to delay marriage until age 21 and delay child birth until age 21. But the same thing is not required for the W&W SS.

To be considered a full-time worker under the S&H SS, an individual needs to live in a family where the “family head” (a Census concept that was initially used to mean the man of the house, but then was changed to mean something more women-inclusive, but now just means whoever answers the survey questions) has to work 35+ hours a week and 40+ weeks a year. In the W&W SS, an individual is considered a full-time worker if they individually (1) worked 35+ hours a week and 50+ weeks a year or (2) are married and watching kids or (3) are in college.

The reason for these differences is that the SS is not some kind of time-immemorial wisdom about poverty. Up until the 1970s, the majority of US adults did not have a high school degree and a little less than half of women had their first child before the age of 21. Almost nobody in the history of the world has followed this sequence.

The SS is instead an ad-hoc way of expressing the authors’ personal cultural preferences at this moment in time. If educational attainment continues to rise, eventually college will replace high school in the SS, and if age of first birth continues to rise, so too will the SS-approved age of first birth. Indeed, I suspect that if S&H were writing their book today, their birth-delay rule would be set at age 25, as bourgeois culture is nowadays pretty disapproving of a 21-year-old having kids.

Even the differences between S&H and W&W reflect disagreements each of them have about culture. For instance, W&W do not believe in delaying childbirth while S&H are big supporters of it. In his other writing, Wilcox laments the fact that having children has come to be seen as a capstone rather than a cornerstone of adulthood. In her other writing, Sawhill advocates free IUDs for poor women. The precise content of the SS gives you more insight into the cultural views of the author than the causes of poverty.

The Success Sequence Excludes Two-Thirds of Poor People

If you are trying to understand where poverty comes from in a capitalist society, the Success Sequence is not going to help very much. This is because the SS analyses all begin by excluding the vast majority of poor people in the country. W&W only looks at one wave of individuals who are between the ages of 28 and 34, which obviously excludes the vast majority of the population as well as the vast majority of poor people.

You might give W&W a pass on this because of the data they are working with, but S&H’s analysis uses the CPS ASEC, which provides a sample of the entire population. They really could see where the poverty is coming from, but instead decide at the very beginning of their analysis to exclude from their consideration (1) families with elderly people in them, (2) families with disabled people in them, and (3) families where every member is below the age of 25.

In the 2019 ASEC, these exclusions remove 117.8 million people (36 percent of all people) from the population. More importantly, these exclusions remove 38.5 million people who are poor based on market income, which is 65 percent of all people who are poor based on market income.¹

This is not surprising of course as elderly people, disabled people, and students generally receive very little from factor payments, which is why they usually get benefits from the welfare state. What is surprising is an inquiry into the sources of poverty that starts by intentionally excluding these groups.

The Success Sequence Is Not A Sequence

Recall from above that Caplan’s version of the SS is:

- Finish high school.

- Get a full-time job once you finish school.

- Get married before you have children.

This is presented as a sequence of steps that you can complete as if in a to-do list and then be assured you aren’t going to be in poverty. But finishing high school is the only step that can actually be crossed off a list. The full-time job and marriage prongs are actually current statuses not steps.

A person who finishes high school, gets a full-time job once they finish school, and then gets married before they have children is counted as following the success sequence until something unfortunate happens to them, at which point they are reclassified as not following the success sequence.

For instance, if someone who had otherwise been following the success sequence loses their job and falls into poverty as a result, this does not count as a success sequence follower who fell into poverty. Instead, in both S&H and W&W, this person’s job loss makes them fail the “work full time” rule and therefore moves them into the “did not follow the success sequence” bucket, which is then perversely used to prove how effective the success sequence is.

Similarly, if your spouse divorces you and you get custody of the kids and you fall into poverty as a result of the divorce, you get recategorized as not following the success sequence even if you checked off all the boxes in the prior years. Weirdly, the divorced parent who does not wind up with custody of the kids can actually be scored as following the success sequence in S&H because they show up in the ASEC as a childless unmarried person.

If your spouse dies, it appears that you would also show up as not following the SS in W&W, though spousal death is probably not too relevant for ages 28 through 34. In S&H, spousal death strangely does not get you recategorized as someone who did not follow the success sequence even though spousal divorce does. Death and divorce are of course functionally equivalent, except that an alive ex-spouse could transfer you some income while a dead spouse cannot. But, as discussed already above, these rules are not about poverty but about what the author approves of. S&H are sympathetic to widows but not to divorcees, so the former gets the SS nod while the latter does not.

Once you understand who the Success Sequence excludes from the analysis (elderly, disabled people, and students) and how it reclassifies people when they hit an economic bump (job loss, death of spouse, divorce, leaving the workforce to care for a family member), it becomes clear that the Success Sequence is just a data-cutting game, not a serious effort to address the causes of and solution to poverty.

Poverty Is Simple

The saddest thing about the SS is that, in trying to make poverty seem like a simple problem, it actually makes it way more complicated than it really is.

In a capitalist society, the national income is distributed using factor payments, i.e. payments to capital and labor. Capital income is extremely concentrated and so it is not a huge factor when it comes to keeping people out of poverty. Labor income is much less concentrated, but only half of the population receives labor income. The other half — children, elderly, disabled, students, caregivers, and the unemployed — do not work and are therefore almost entirely locked out of the direct distribution of income.

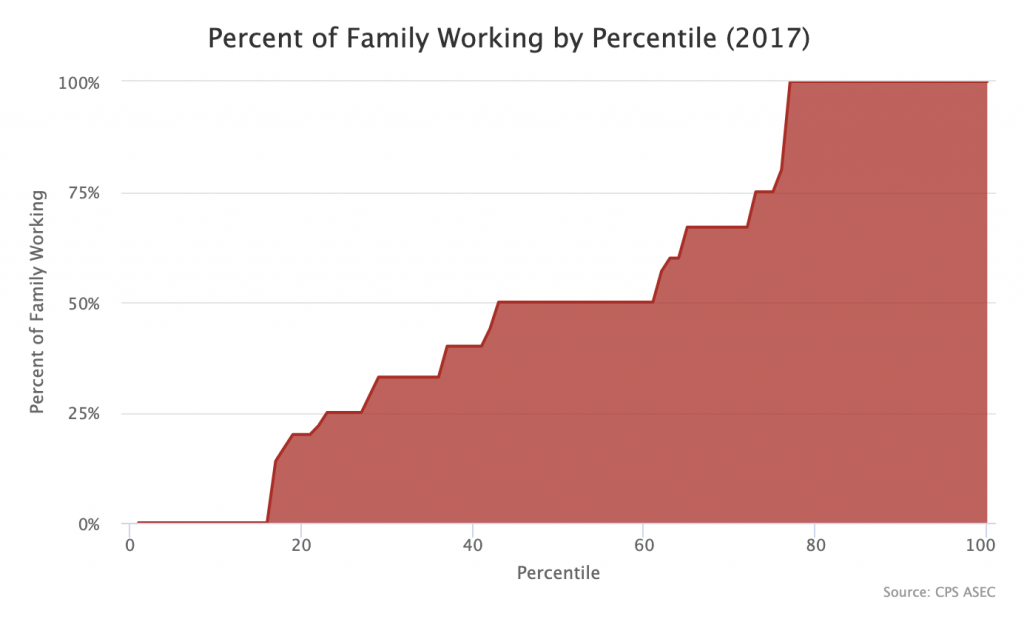

The percentage of people who are working varies a bit depending on the macroeconomic situation, but not that much. So at any given time, the challenge of poverty is just the challenge of moving money from the right side of the above graph to the left side of the above graph.

For the purposes of our poverty metrics, this challenge can be met by either (1) combining people on the right side of the graph in family units with people on the left side of the graph or (2) using the welfare state to transfer money from the right side of the graph to the left side of the graph.

From the perspective of an overall society, if you are trying to limit poverty solely through approach number one, what you want to do is match every worker with a nonworker and then combine as many of these worker-nonworker duos as you can into each family unit. The optimal family would be something like a unit with 10 workers and 10 nonworkers living together in a single dwelling. This ensures that each unit has the same 1:1 ratio of workers to nonworkers, ensures income from workers spreads to nonworkers, and ensures that economies of scale (which are reflected in poverty lines) are as high as possible.

In practice of course, family units are not that big and most of them do not have a 1:1 ratio of workers to nonworkers. Instead, nonworkers are distributed very unevenly across family units, as we can see in the graph below.

When nonworkers are spread very unevenly across family units, the necessary redistribution from workers to nonworkers doesn’t happen, and so you get high poverty. You could certainly try to rearrange workers and nonworkers across family units to fix this, but I don’t see any plausible policy for doing that and trying to get people to live with one another when they don’t really want to also seems a bit repugnant to me as a philosophical matter.

Rather than redistributing people across family units, the welfare state approach attacks the poverty problem by redistributing income across family units. By levying a tax on all workers in order to fund cash benefits for nonworkers (old-age pensions, disability benefits, child allowances, caregiver allowances, and unemployment benefits), the welfare state ensures that income from workers spreads to nonworkers regardless of the composition of each family unit. This approach effectively achieves the desired 1:1 worker to nonworker ratio across the entire society and, if sufficiently comprehensive and generous, brings poverty down to a very low level.

If we switch our perspective away from a society trying to avoid poverty and towards an individual trying to avoid poverty, the analysis from above also provides a pretty straightforward guide. The two rules of individual poverty avoidance are (1) maximize the number of workers in your family unit, (2) minimize the number of nonworkers in your family unit. Five workers is better than four, which is better than three, two, one, and zero. Likewise, zero nonworkers is better than one, which is better than two, three, four, and five.

Bringing workers into your family is not something that you can just snap your fingers and do. You’ll need to learn relationship-building skills, among other things. Avoiding nonworkers is something you have total control over though. To minimize your chance of poverty, you should not have kids and you should avoid living with elderly people, disabled people, unemployed people, and students, to name a few.

To the extent that the Success Sequence gestures towards anything that’s relevant to individual strategies for poverty avoidance, it only does so because it is tracking the two rules above.

For example, when the SS says marriage reduces poverty, it is just clumsily gesturing towards rule number one: maximize the number of workers in your family unit. Indeed, if you push Wilcox enough on this, he’ll eventually admit this. The problem of course is that marriage does not always increase the number of workers in your family unit, e.g. if you marry a disabled person, and so a general recommendation of it is a bit misleading. The other problem is that the logic of adding workers to your family to avoid poverty does not stop at adding one worker. If marriage is your way of adding workers to your family, then the SS should be promoting polygamous marriages.

In other cases, the SS leads you in exactly the wrong direction. For example, when it talks about when and under what circumstances you should have kids, it should instead be telling you to never have kids. Having kids violates rule number two — minimize the number of nonworkers in your family unit — and can only act to increase your risk of poverty by increasing the amount of money you must earn each year to stay above the poverty line.

I could go on, but I have already gone on too long. In sum, the SS is a wildly misleading data-cutting game that obscures the rather simple mechanics of poverty, both on a social and individual level. Someone who is writing a book on poverty that really wants to approach the issue in the emotionless way it deserves to be approached should not fall prey to such a half-baked just-so ruse.

1. Disability is determined using DIS_HP. Market income is defined as FTOTVAL – FSSVAL – FSSIVAL – FUCVAL – FVETVAL – FWCVAL – FPAWVAL. For the poverty line, I use FPOVCUT. See ASEC data dictionary.