Over at The Atlantic, Annie Lowrey asks “Could Index Funds Be Worse Than Marxism?” In her piece, Lowrey discusses two arguments about index funds: (1) that they are destroying capital allocation because they invest blindly in everything and (2) that they are causing price hikes because they are facilitating the common ownership of competitors.

Capital Allocation

The first argument has been floating around for a few years now and, so far, seems to lack a significant empirical basis. Even the theory behind it is a little shaky. If active investors were actually better capital allocators than passive investors, then they should outperform passive investors. But they don’t. Doing a bunch of research and then failing to pick the right company is ultimately no different than doing no research and failing to pick them, though one employs a lot of unnecessary bankers and the other does not.

Furthermore, the stock market is not even a place where companies raise money. It’s a place where early investors cash out and where people swap around existing shares in the secondary market. When firms want to raise cash, they use retained profits or go to the debt markets where they still have to endure some individual scrutiny.

Common Ownership

But in this piece I want to focus more on the second argument, which has gathered steam a lot more recently. According to this argument, if you allow the same investors to own all the firms in a given sector, then this will, through various formal and informal mechanisms, result in those firms raising their prices. Undercutting a competitor on price may be good for your firm individually, but if your firm’s owners also owns your competitors, then this kind of competition hurts your investors bottom line.

This is an intuitive argument and Lowrey cites to a study that finds that something like this has happened in the airline industry. But the authors of that paper put out a second study that reaches a different conclusion on the question of common ownership, at least as it pertains to the Big 3 index fund companies: Vanguard, Blackrock, and State Street.

In the new paper, the authors distinguish between intra-industry common ownership, which refers to a situation where many of the firms inside a given industry are commonly owned, and inter-industry common ownership, which refers to a situation where a common owner owns firms across many different industries. Intra-industry common owners tend to increase prices while inter-industry common owners tend to decrease prices.

This makes intuitive sense. Price hikes in one industry have negative effects on other industries, which an intra-industry common owner does not care about but which an inter-industry common owner does care about.

The Big 3 index fund companies are effectively universal owners, meaning they have common ownership across the entire market. So they are both big-time intra-industry common owners as well as big-time inter-industry common owners. As a result of this, they are tugged in both directions when it comes to prices.

Ultimately, the authors conclude that the net effect of these conflicting pressures is lower prices not higher prices. In their words: “the overall effect of the Big Three on prices is negative.”

Norway Shows the Way

Late last year, the Norwegian statistical agency put out a study about market power and inequality in the country. This study was not about concentration in the form of common ownership but rather concentration in the more conventional form that people talk about, meaning a smaller number of firms dominating a specific industry.

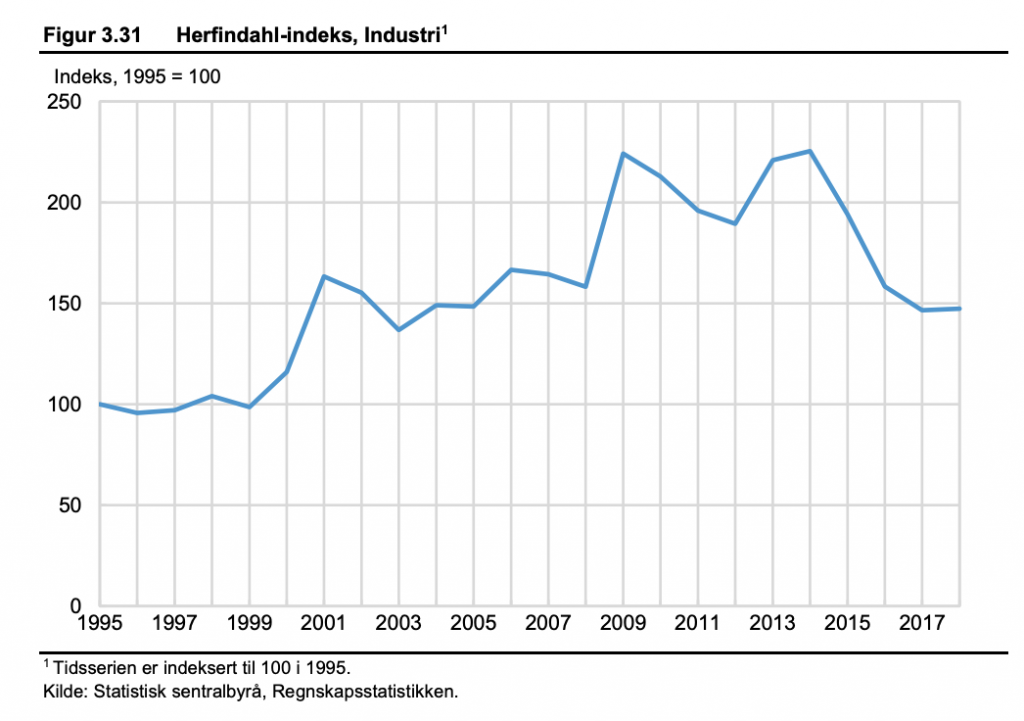

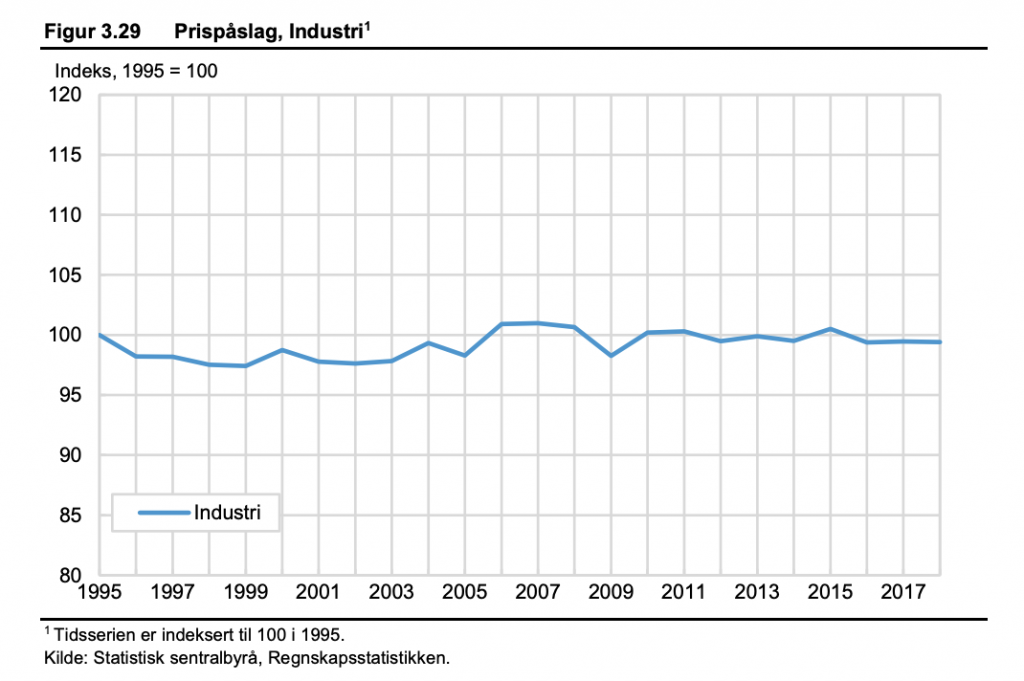

Overall the study finds that, despite increases in concentration, aggregate price mark-ups in the country have not increased. The following graphs from the industrial sector are illustrative. In the first one, we see how much more concentrated the industrial sector became over time: 50% more concentrated as measured by the HHI. In the second one we see the change in price markups over the same period: 0.

The study also included an analysis of the change in labor’s share of income over time, which is where things get really interesting.

Increasing concentration and market power could result in lower labor shares, which is generally seen as a bad outcome. The study finds that this has not been true for Norway generally, but that you do see lower labor shares in some Norwegian industries. However, there is a big caveat to that:

At the same time, the reduction is most pronounced in industries in which the state receives a large share of profits either directly, through ownership, or indirectly through taxes. To the extent that this income is used for public investment and consumption, the reduction in demand due to a falling labour share will be curbed.

That’s right: Norway’s high levels of state ownership of industry largely moot the question of labor’s share. Profits going up matters when a small class of people owns all the assets. But when the state owns them, it’s just more revenue for welfare.

I bring this up because I think it, along with the recent research on the Big 3 index funds, makes a strong case for the social wealth fund approach to the question of how companies should be owned. Universal owners, like the SWF, actually generate lower prices not higher prices, and, when companies are publicly owned, any increase in capital share resulting from market power just redounds to the public anyways.