To be eligible for paid leave under the old FAMILY Act proposal, you need to have worked at least 6 quarters, worked for the lesser of 20 quarters or half the quarters since your 21st birthday, and worked in the last 12 months. According to the CBO, this work history requirement would render 30 percent of new parents ineligible for the FAMILY Act’s paid leave benefit.

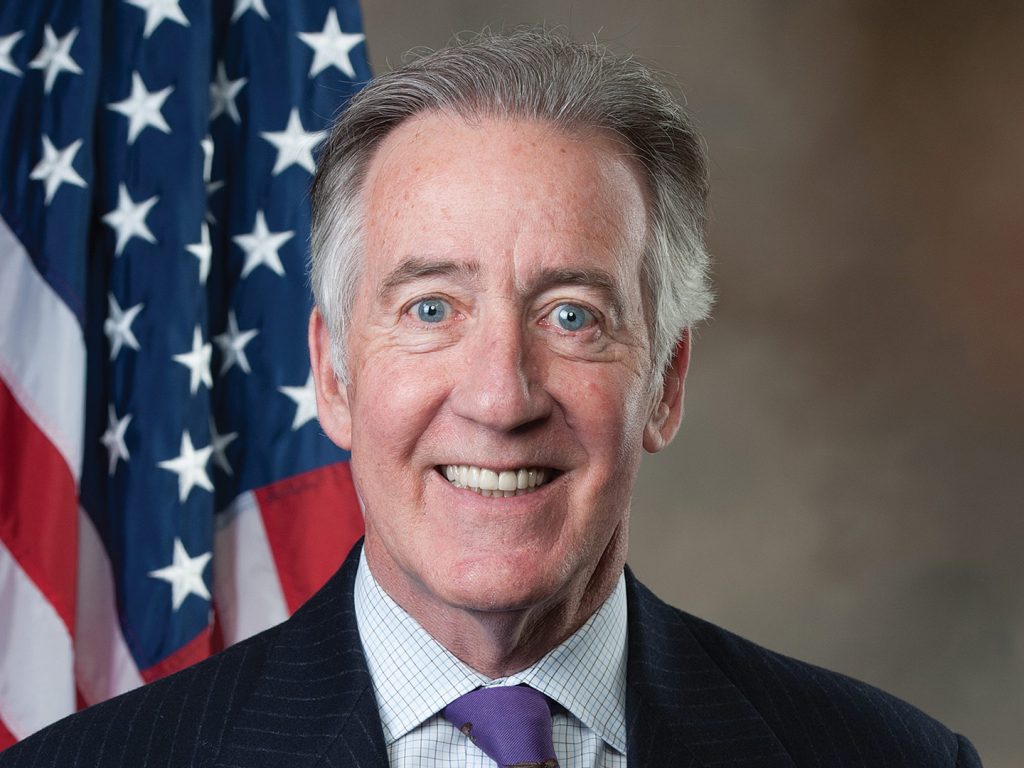

More recently, an alternative to the FAMILY Act, which was proposed by Representative Richard Neal, has been gaining traction in the House. Under this alternative, individuals are eligible for paid leave if they “have had earnings in the 30 days prior to the first caregiving day as well as during the 8-calendar-quarter period preceding their caregiving leave.” Insofar as having earnings in the last 30 days also means you have had earnings in the prior 8 quarters, this simplifies down to a requirement that an individual have worked in the last 30 days.

There have so far been no estimates of how many new parents this 30-day rule excludes. Such an estimate is difficult to produce as it requires data that links birth events and earnings histories, which as far as I know is not publicly available.

But we can still get a decent ballpark estimate by combining information from the National Center for Health Statistics births microdata with information from the monthly Current Population Survey microdata. The NCHS data provides detailed information about all of the births that occurred in a given year, including the month the birth occurred and the age and race of the birth mother. The monthly CPS data provides detailed labor market information, including the employment status of all women based on their age and race.

For this exercise, I divided all of the 2019 births into 288 buckets based on month of birth, age of birth mother, and race of birth mother. Then I determined what percent of women in those 288 buckets were either not in the labor force or unemployed for at least 4 weeks. Such women are not eligible for paid leave under Neal’s plan. Then I applied these 288 percentages to the corresponding 288 buckets of births to estimate the total number of births that are ineligible for paid leave.

Using this rough method, 42 percent of women who give birth in a given year will not be eligible for paid leave under Neal’s plan because they do not satisfy the 30-day work requirement rule. For various technical reasons, I have not tried to do the same analysis for fathers, but I would suspect the percentage is lower for them.

Needless to say, this is a really bad way to design a program and also comically inattentive to the realities of pregnancy.

For many women who are employed in physical or hazardous jobs, working in the last 30 days of pregnancy is extremely difficult if not impossible. This is why many other countries, like Finland, allow women to start their maternity leave 5 to 8 weeks before their expected due date if they’d like to. Denying benefits to women who need to take off their last month of pregnancy — not just denying them benefits during their last month of pregnancy but even after they give birth — is completely nuts.

The problems are not just for physical jobs or difficult pregnancies either. Many women will fail to meet the 30-day work rule because they are disabled and unable to work or because they are unemployed, in some cases due to difficult-to-prove pregnancy discrimination. Then there are of course women who give birth prior to joining the workforce, such as those still in education.

For both the old FAMILY Act and the new Neal proposal, there is an easy solution to this eligibility problem. The solution is to add a sentence or two to the bill that states that all new parents who do not meet the work history requirements are still eligible for the minimum monthly paid leave benefit. This does not solve all the problems with these bills — for a flawless paid leave design, see my Family Fun Pack — but it does a decent job of patching this specific problem. And it is hard to understand why the Democrats would want to oppose it.