Every few months, a prominent person or publication points out that McDonalds workers in Denmark receive $22 per hour, 6 weeks of vacation, and sick pay. This compensation comes on top of the general slate of social benefits in Denmark, which includes child allowances, health care, child care, paid leave, retirement, and education through college, among other things.

In these discussions, relatively little is said about how this all came to be. This is sad because it’s a good story and because the story provides a good window into why Nordic labor markets are the way they are.

McDonalds opened its first store in Denmark in 1981. At that point, it was operating in over 20 countries and had successfully avoided unions in all but one, Sweden.

When McDonalds arrived in Denmark, the labor market was governed by a set of sectoral labor agreements that established the wages and conditions for all the workers in a given sector. Under the prevailing norms, McDonalds should have adhered to the hotel and restaurant union agreement. But they didn’t have to do so, legally speaking. The union agreement is not binding on sector employers in the same way that a contract is. You can’t sue a company for ignoring it. It is strictly “voluntary.”

McDonalds decided not to follow the union agreement and thus set up its own pay levels and work rules instead. This was a departure, not just from what Danish companies did, but even from what other similar foreign companies did. For example, Burger King, which is identical to McDonalds in all relevant respects, decided to follow the union agreement when it came to Denmark a few years earlier.

Naturally, this decision from McDonalds drew the attention of the Danish labor movement. According to the press reports, the struggle to get McDonalds to follow the hotel and restaurant workers agreement began in 1982, but the efforts were very slow at first. McDonalds maintained that it had a principled position against unions and negotiations and press overtures were unable to move them off that position.

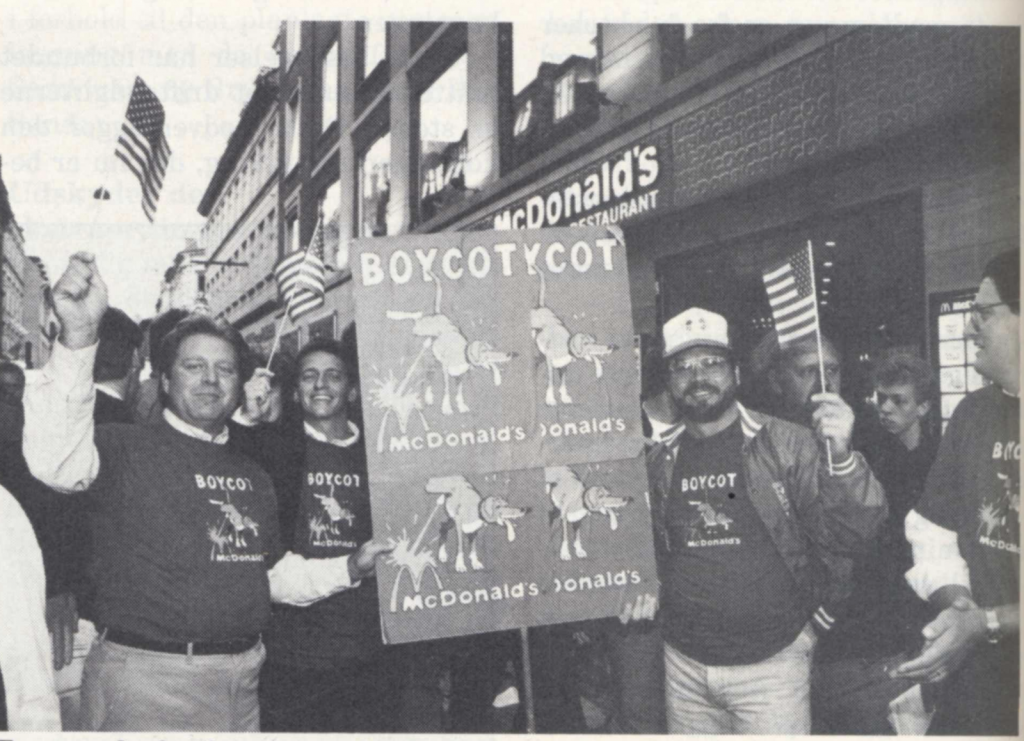

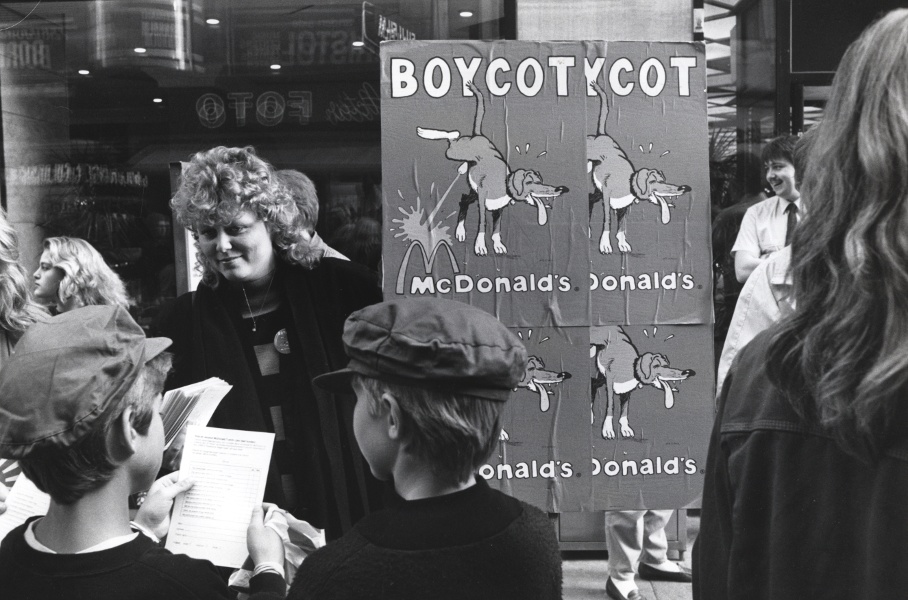

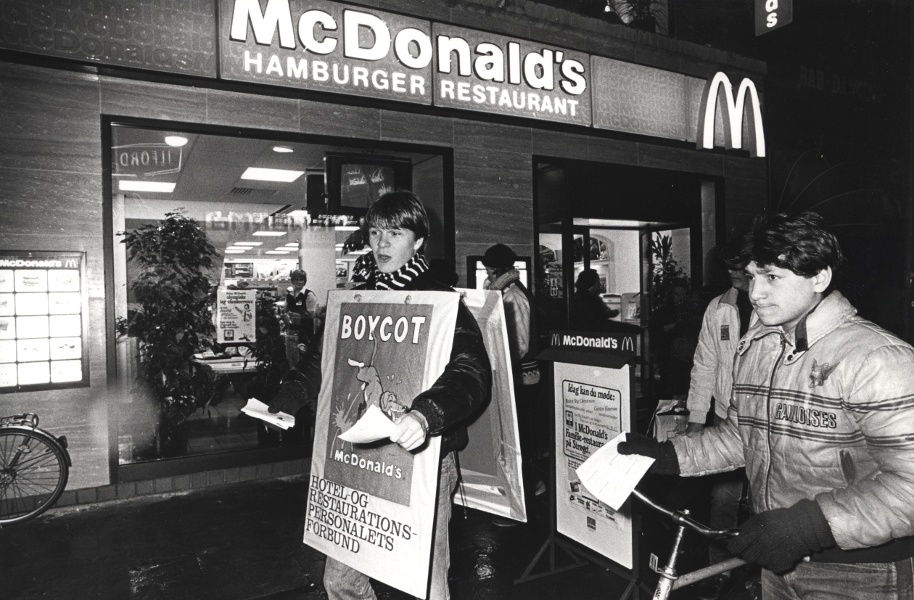

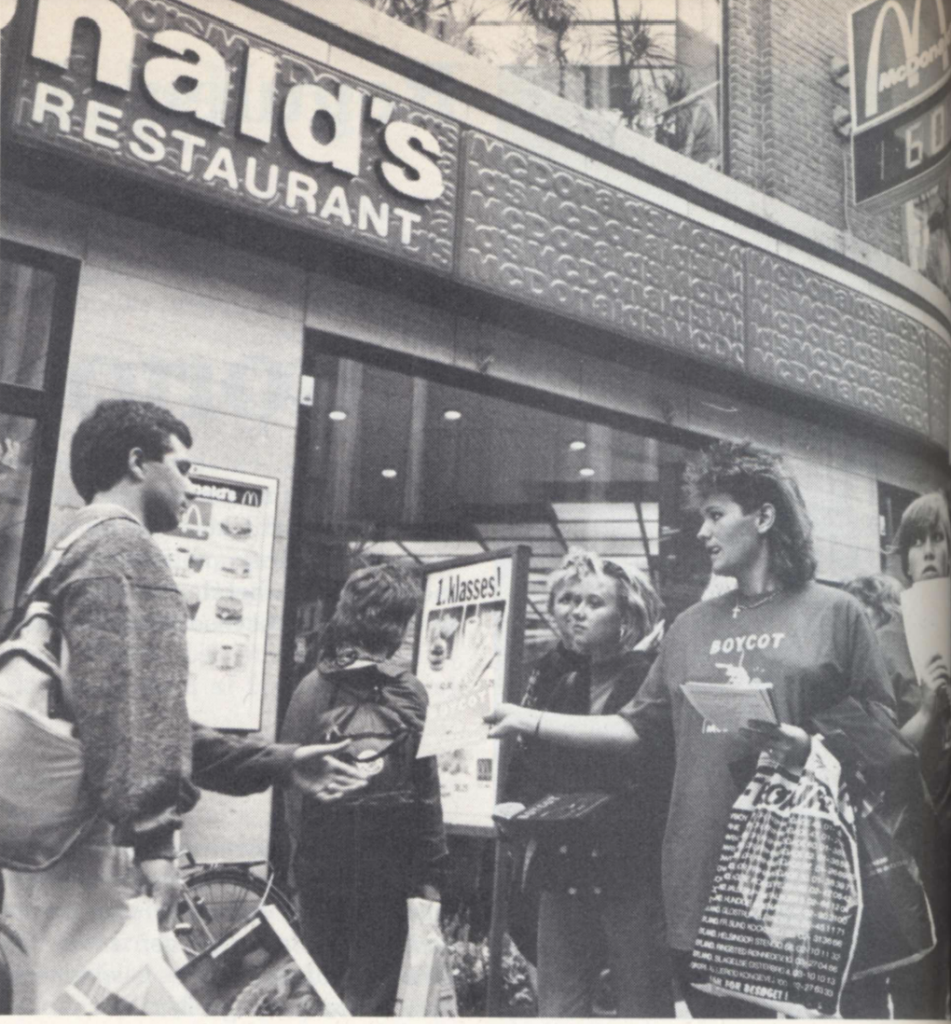

In late 1988 and early 1989, the unions decided enough was enough and called sympathy strikes in adjacent industries in order to cripple McDonalds operations. Sixteen different sector unions participated in the sympathy strikes.

Dockworkers refused to unload containers that had McDonalds equipment in them. Printers refused to supply printed materials to the stores, such as menus and cups. Construction workers refused to build McDonalds stores and even stopped construction on a store that was already in progress but not yet complete. The typographers union refused to place McDonalds advertisements in publications, which eliminated the company’s print advertisement presence. Truckers refused to deliver food and beer to McDonalds. Food and beverage workers that worked at facilities that prepared food for the stores refused to work on McDonalds products.

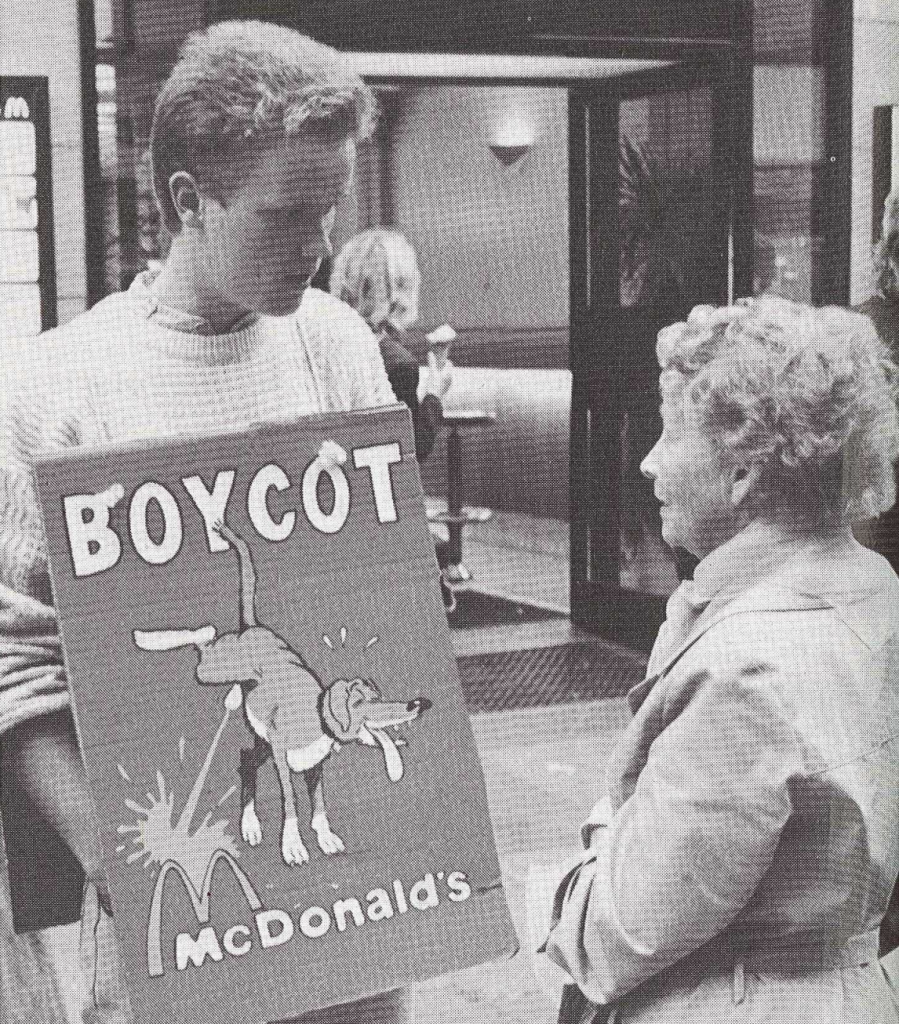

In addition to wreaking havoc on McDonalds supply chains, the unions engaged in picketing and leaflet campaigns in front of McDonalds locations, urging consumers to boycott the company.

Once the sympathy strikes got going, McDonalds folded pretty quickly and decided to start following the hotel and restaurant agreement in 1989.

This is why McDonalds workers in Denmark are paid $22 per hour.

I bring this up because people say a lot of things about the economies of the Nordic countries and why they are so much more equal than ours. In this discussion, certainly the presence of unions and sector bargaining comes up, but rarely do you get a discussion of just how radically powerful and organized the Nordic unions are and have been. If you didn’t know better, you’d think the Nordic labor market is the way it is because all of the employers and workers came together and agreed that their system is better for everyone. And while it’s true of course that, on a day-to-day basis, labor relations in the countries are peaceful, lurking behind that peace is often a credible threat that the unions will crush an employer that steps out of line, not just by striking at one site or at one company, but by striking every single thing that the company touches.

We saw this most recently in Finland in 2019 when the state-owned postal service decided to cut the pay of 700 package handlers by moving them to a different sector agreement than the one they were currently being paid under. The unions responded by striking airlines, ferries, buses, trains, and ports. In the aftermath of these strikes, the pay cuts were reversed and the prime minister of the country resigned.

When I bring this up, people sometimes respond by saying that these kinds of strikes are illegal in the US. This is a true and worthwhile bit of information, but insofar as it is meant to imply that the different legal environment is what accounts for the labor radicalism, this obviously has things backwards. The laws aren’t driving the labor radicalism, but rather the labor radicalism is driving the laws.

We can see this clearly in another recent example, this time from Finland in 2018. There, the conservative government was preparing to pass a law that would make it easier for employers with 20 or fewer employees to fire workers. The stated purpose of this was to stimulate hiring by making it easier to fire and thus less risky to hire — the usual stuff.

The Finnish labor movement did not like this idea and called a massive political strike that sidelined workers in a bunch of different sectors. In response to the strike wave, the government changed the bill so it only applied to employers with 10 or fewer employees. The strikes continued and they changed the bill again, this time so it just stated generally that courts should consider an employer’s size when adjudicating wrongful dismissal cases. This was acceptable to the unions since, according to them at least, Finnish courts already do this and so the bill was basically moot. So they stopped striking.

One can only imagine what would happen if the Finnish government tried to ban sympathy strikes in the same way the US government has here.

If we are ever going to get to Nordic levels of equality, it is really hard to imagine doing it without building a similarly powerful labor movement. You can certainly get some of the way there, such as by copying certain welfare programs, but without the unions, you’ll always be missing a key piece. And while legal and policy reforms can help build the labor movement some, the power of organized labor is not ultimately rooted in the state, but rather in the ability to halt production and wreak havoc even when the state is aligned against it.

McDonalds doesn’t pay Danes high wages because of a statutory wage floor or even because the state stepped in to enforce a collective bargaining agreement. They pay high wages because back in the 1980s, Danish unions flipped a switch and turned the whole business off, and McDonalds doesn’t want to find out whether they would do it again.

This is where we need to get to.