A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a piece pointing out that the Democrats’ child care plan would hugely increase costs, e.g. by $13,000 for infant care, for unsubsidized parents. This generated a very negative and mostly unspecific reaction from child care advocates that varied between saying I was wrong without saying exactly that or saying it’s not politically wise to talk about such things right now (I, II).

Today, the District of Columbia’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education (DC OSSE) released a report about a DC child care proposal that reaches the exact same conclusion that I did.

Cost Hikes

In 2018, the DC government passed the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act, which, among other things, directed the OSSE to analyze what would happen if the city required child care workers to receive “compensation equivalent to an elementary school teacher employed by the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) with the equivalent role, credentials, and experience.”

Nearly identical language, probably written by the exact same people, is found in the Build Back Better (BBB) child care plan currently being debated in Congress. That language requires states to ensure that child care worker wages “are equivalent to wages for elementary educators with similar credentials and experience in the State.”

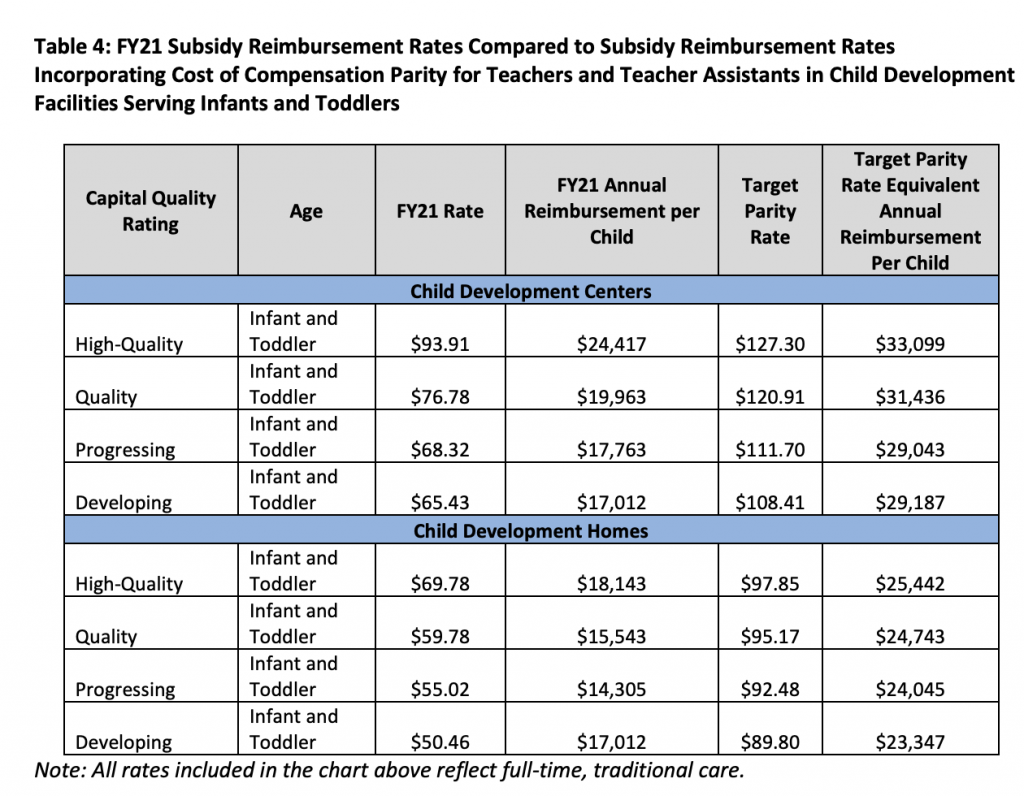

Using a very detailed cost estimate model, which incorporates data directly from providers, OSSE concluded that the per-child cost of providing center-based toddler and infant care would increase by about $12,000 in most centers. In centers that are already considered high-quality, the cost would increase by about $9,000.

When digesting these numbers, it’s important to note that the DC minimum wage is currently $15.20 per hour, which is 25 percent higher than the national median child care worker wage of $12.24. Areas where child care wages are currently lower than that would likely see costs grow by a higher amount.

The OSSE analysis also includes infant and toddler care together in its averages. In general, infant care would increase by more than the average amount while toddler care would increase by less.

Finally, the OSSE report only analyzes pay increases for direct child care staff, ignoring any spillover effects that these increases would have on the wages of center directors and similar staff. This approach likely understates how much costs would rise, according to the OSSE:

This estimated cost also does not include the costs of increasing compensation for other staff in child development facilities serving infants and toddlers, such as center directors or preschool teachers, because the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act does not address compensation for these staff. However, facilities that increased compensation for infant and toddler teachers and assistants would likely need to increase compensation for these staff as well, which would further increase the costs for child care providers.

No matter how you cut it, it’s clear enough that this kind of mandate is going to cause the unsubsidized cost of child care to increase dramatically, just as I said a couple of weeks ago.

Unsubsidized Parents Get Hit

Increasing child care worker wages while also subsidizing the cost for parents is potentially a big win-win for everyone involved. But the current BBB child care plan only subsidizes costs for parents with incomes below a certain threshold, as outlined in the table below.

| Year | Eligible Incomes as Percent of State Median Income |

| 2022 | Below 100% |

| 2023 | Below 125% |

| 2024 | Below 150% |

| 2025 | Below 250% |

| 2026 | Below 250% |

| 2027 | Below 250% |

Families with incomes below these levels will receive subsidies that ensure they don’t have to pay the increased costs that will result from the increased child care demand and the wage, quality, and credential mandates contained in the legislation. Families with incomes above these levels will have to pay the full child care price, which will be massively higher than it was before.

The OSSE explains the problem with this model very well.

Forty-nine percent of child development centers participating in [the subsidy system] have fewer than half of their seats occupied by children receiving subsidies, as do 45 percent of homes. Because increasing staff compensation would increase the costs to deliver care for both subsidy and non-subsidy children, these child development facilities would need to either raise parent tuition payments or identify additional revenue sources to cover the increased costs to deliver care to non-subsidy children.

OSSE continues:

The Birth-to-Three for All DC Act would require any child care provider that accepts child care subsidies and serves infants and toddlers to pay teachers and teaching assistants according to the compensation schedule—whether subsidized children account for 1 percent or 100 percent of their enrollment. However, the increased subsidy rates called for by the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act apply only to infants and toddlers participating in the subsidy program. As a result, the many providers who serve a mix of subsidy and non-subsidy children would need to increase the rates charged to private pay parents in order to cover the costs of increased compensation.

Lastly OSSE talks about the overall labor market dynamics of such a move, which will make it impossible to escape the consequences of it, even for centers that strategically elect not to participate in the subsidy program:

Further, because both subsidy and non-subsidy child care facilities hire staff in the same labor market, increasing compensation for teaching staff in subsidized programs will place wage pressure on nonsubsidy programs, even though these programs do not benefit from increased subsidy rates. To pay for increased compensation, non-subsidy providers would need to increase prices charged to parents; those serving families who could not afford to pay higher costs might be forced to close. Any of these outcomes could reduce affordability of and access to child care in the District.

The “unintended negative consequences to the child care market” of this proposal are bad enough that the OSSE ultimately recommends against doing it.

First Three Years Will Be Tough

Some advocates seem to think that, because the BBB legislation gives states up to three years to implement the wage mandates, the associated cost hike wont really hit until 2025, at which point the only people dinged by it will be families with incomes above 250 percent of the median, which is a pretty high amount of income.

But this is not remotely credible.

According to the BLS, child care workers are currently paid less than 98 percent of workers in the economy. The child care workforce is also currently wracked by shortages — there are 10 percent fewer child care workers now than before the pandemic — within what appears to be a fairly tight labor market with substantial child care demand.

The idea that you can simultaneously (1) remove all child care price barriers for the bottom half (or more) of kids, (2) keep paying child care workers at the 2nd percentile of the wage distribution, and (3) find enough workers to actually supply the increased child care demand, is just laughable. Yet this is how some child care advocates seem to think the first three years of the program will work.

You simply can’t have huge subsidy increases resulting in much higher demand without having wage hikes in a sector that pays right about the lowest wage in the society. Where are the workers going to come from?

What To Do

Unless advocates think that the OSSE is also part of the Bad Faith Bruenig conspiracy, they need to start taking this problem a lot more seriously than they currently are. And by that I mean actually making changes to the legislation that might fix it, not trying even harder to snow over credulous journalists with deceptive hand-waving and strenuous objecting.

My proposal is to make child care free for ages 0 to 2 just the same way that Democrats are proposing to make it free for ages 3 and 4. And to the extent that this kind of system cannot be ramped up overnight, we can create a temporary (or even permanent) home child care allowance program that allows parents who would prefer to care for their young children in their home, rather than use child care services, to receive a cash payment to do so instead. This would take pressure off the system as it is being built up without leaving anyone out of the overall child care benefit scheme.