Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman put out a study this week that, among other things, tries to identify, whether rich people are disproportionately admitted to top universities and, if so, why. This has been a topic of intense interest in the discourse for as long as I have been involved in it and I think this study helpfully resolves some of the longstanding disputes in that discourse.

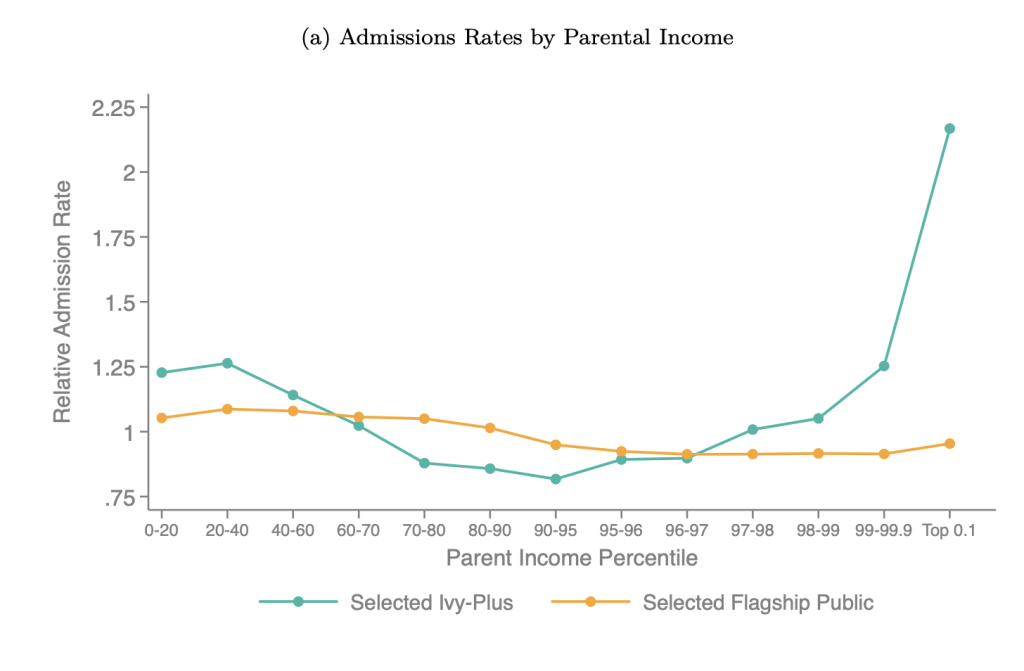

For starters, while it is true that children from the richest families have better academic qualifications than the population overall, it is not true that this fully explains their greater representation in the top universities. After controlling for test scores, the richest kids are admitted at more than twice the rate as the population overall. Notably, this admissions boost is found among the 12 Ivy-Plus schools analyzed in the study, but not at flagship public universities.

Despite what some think, the overrepresentation of the rich at the top universities is not driven solely or even primarily by legacy preferences. According to the paper, after controlling for test scores, legacy preferences explain about 30 percent of the surplus rich attendees, while higher application rates, higher matriculation rates, better nonacademic credentials, and athlete preferences explain the remaining 70 percent.

If you take application rates and matriculation rates out of the equation, leaving only the factors related to how universities make admissions decisions, legacy preferences account for 46 percent of the surplus rich attendees while better nonacademic credentials account for 30 percent, and athlete preferences account for the remaining 24 percent.

A debate has raged for many years about how much weight to put on test scores versus grades and nonacademic factors. One popular view that has emerged on the left is that test scores should be augmented, if not entirely replaced, by more holistic considerations like personal statements, extracurricular activities, recommendations, and things of that nature. This view appears to be primarily motivated by the belief that such augmentation will benefit kids from poorer families.

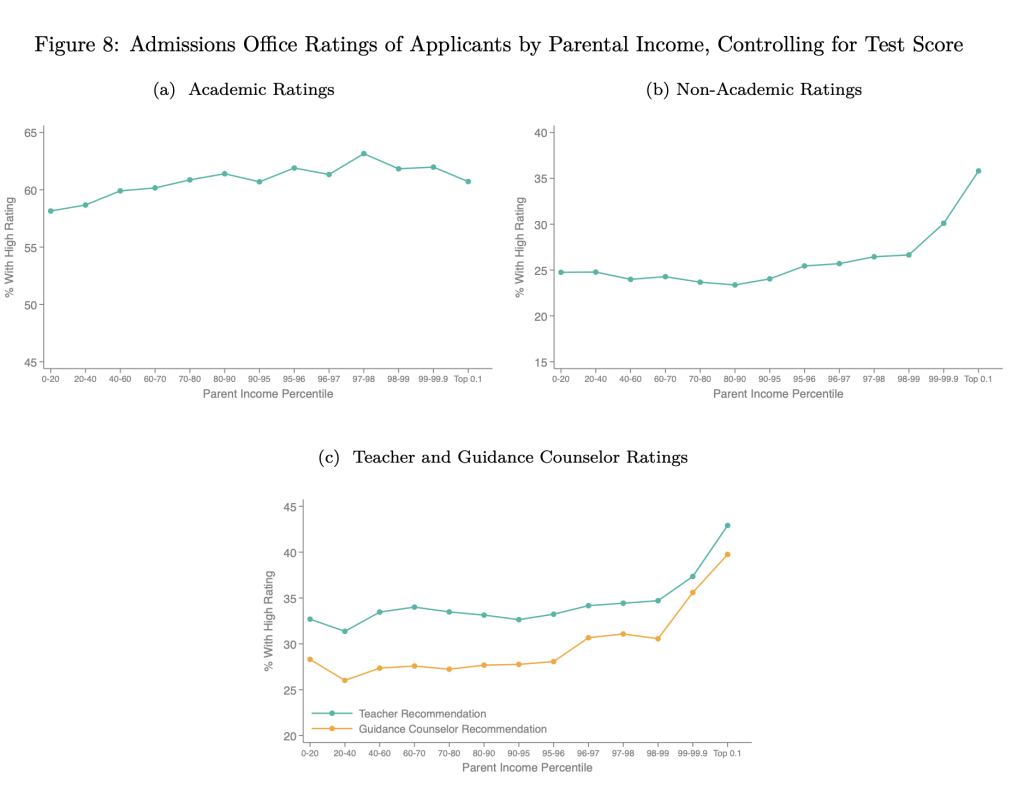

The alternative view is that these holistic considerations actually favor the rich more because the rich will tend to accumulate better recommendations, more extracurricular activities, and even better grades because they have more information and are more strategic about preparing a college resume.

This study suggests that the alternative view is the correct one. When comparing students with similar test scores, every other consideration — including academic ratings (grades), non-academic ratings (extracurriculars), guidance counselor recommendations, and teacher recommendations — favors the rich, with extracurriculars and recommendations especially favoring the rich.

If the goal is to eliminate the extent to which rich kids are overrepresented at top universities relative to their test scores, the study points to the existence of some fairly straightforward ways to do so. Legacy and athlete preferences can be zapped immediately. Non-academic factors like recommendations and extracurriculars could be hugely down-weighted or eliminated entirely. Other targeted encouragement could increase the application and matriculation rates of the non-rich.

But this is really not the goal of top universities. These schools already have vastly more qualified applicants than they have seats. If they wanted to create classes that were more socioeconomically balanced, they could already do so from their current applicant pool. They choose not to because their goal is, in part, to run the nation’s elite families through their institutions in order to increase their endowments and power in society.

Insofar as a hugely outsized share of the ruling class of the country matriculates through these institutions, it makes sense that they are objects of intense scrutiny. Anything that has to do with the creation and reproduction of the ruling class should be of interest to the public because it has an impact on everyone.

However, many people seem to be interested in these institutions because they think that they are important pieces of our higher education system when that just is not the case. According to the study, the 12 Ivy-Plus schools have an average admissions class of 1,650 and admit around 157 more rich kid than they ought to based on test scores alone. This means that, between these schools, there are around 1,884 seats being misallocated to the rich every year. By comparison, around 4 million kids are admitted at undergraduate institutions in a given year.

The kids who are elbowed out by the 1,884 non-deserving rich kids still attend college, just at a 98th percentile institution, not a 99th percentile institution. The quality of the educational services they receive does not differ, though the prestige, status, and career opportunities made available by their institution does.

Egalitarian reforms to the higher education system should focus on reducing selectivity and making top universities less distinct from the rest of the system. Swapping a few thousand people around the top few percentiles of the university system just isn’t going to do much to create an equal or fair society, if it does anything at all.