A regime of centralized, coordinated bargaining is emerging in California. Through a series of legislative measures, California is shifting toward a bargaining system widely recognized as the gold standard for workers. As California implements these new bargaining structures, questions about their execution and ultimate fate will grow in relevance. Insights into these questions can be gained by examining the world’s best labor institutions: the Nordic Model.

Nordic labor market institutions set the global benchmark for excellence. Nordic countries have high wages, high employment rates, compressed wage differentials, and highly productive and innovative economies. These results are driven in large part by their highly organized workforce and sectoral bargaining.

Although many European countries use some form of sectoral bargaining, the Nordics have a unique approach to it that separates them from their European peers.

Coverage

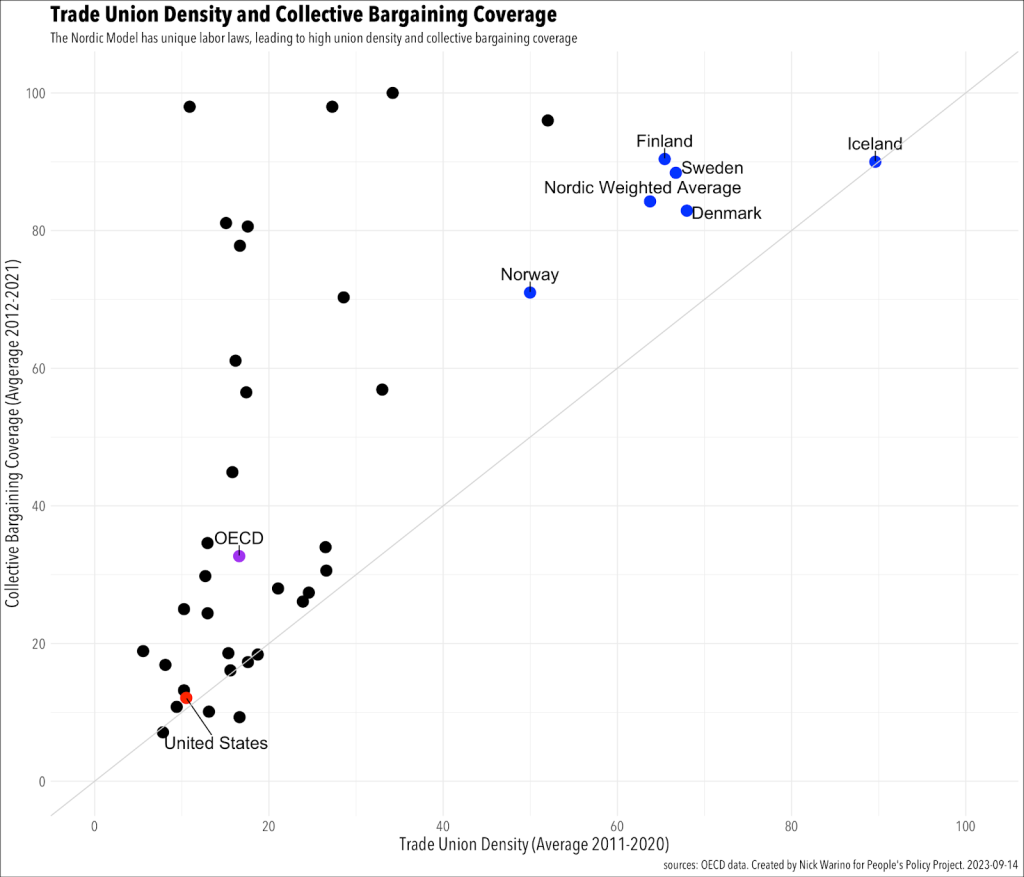

Across all Nordic countries, around 84 percent of the workforce is covered by a collective bargaining agreement, which is seven times higher than the US. Of the 11 countries with a supermajority of workers covered by collective bargaining agreements (CBAs), all 5 Nordic countries are represented, with Finland and Iceland topping the Nordic countries with 90 percent coverage.

The Nordics have the highest union membership rates and even higher collective-bargaining coverage rates. In Finland, Iceland, and to a lesser extent, Norway, union-employer CBAs are extended within the industry, either automatically or through state intervention. Denmark and Sweden lack this extension mechanism, but instead rely on their powerful unions to force nearly all industry employers to use the CBA.

Coordination

In the Nordic Model, both labor and management participate as coordinated entities with clearly defined roles in the bargaining process. On the management side, employer associations are common, representing between 65%-80% of all employers in the Nordics. These groups negotiate with unions to set standards for almost all employers in their sectors. This level of coordination is matched on the labor side, with 50-90% of workers belonging to a union. For the Nordic countries that lack formal extensions of CBAs throughout the respective industries, this coordination ensures wide coverage of CBAs throughout each industry.

Scope

In the Nordic Model, sectoral bargaining is comprehensive, addressing not just wages but also work-life balance, benefits, vocational training, gender equality, and more. For example, the Swedish Livsmedelsarbetareförbundet, Livs (The Food Workers’ Union) boasts about its collectively bargained contract containing “so much more” than pay and reasonable work hours. The contract also covers vacation, overtime, odd-hours pay, pensions, unemployment, and various types of insurance. While the precise scope of these contracts varies by sector and country, they universally adhere to the principle of comprehensiveness.

Organized Decentralization

Since the 1980s, the Nordics—like the rest of Europe—have experienced some form of decentralization of their bargaining regimes. Decentralization can mean moving from “peak level” (economy-wide) coordinated bargaining down to sector level or from sector level to firm level. For the Nordics, decentralization has been organized within the overall sectoral bargaining structure, allowing the sectoral agreements to be floors or frameworks for firm-level bargaining structures to fill in the details or to expand upon.

California’s Emerging Sectoral Bargaining Regime

Since 2019, under the Newsom Administration, California has gradually moved toward coordinated, sectoral bargaining through four bills and one budget action.

The most high-profile move is in the fast food industry. Through the efforts of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which in 2019 began emphasizing sectoral bargaining nationally via its “Union 4 All” campaign, and the broader CA labor movement, AB-257 was signed into law in 2021.

Known as the “FAST Recovery Act,” this bill would establish a statewide “Fast Food Council,” composed of four representatives for labor, four for management, and one independent representative of “the public.” The Council is tasked with negotiating statewide standards for fast-food workers’ wages and working conditions. However, the Council is not allowed to bargain over benefits, including paid-time off. Although organized opposition from the restaurant industry had postponed the law’s implementation pending a 2024 referendum, a recent legislative compromise through AB-1228 ensures that a modified version will take effect in 2024. This agreement includes raising the minimum wage for fast food workers to $20 in 2024 (statewide minimum wage law for all workers will be $16/hr that year).

The fast food industry is not alone in moving towards more centralized, coordinated bargaining. Back in 2019, SEIU joined with AFSCME to push CA into enacting AB-378, the Childcare Providers Act, which allows family child care providers to unionize. This law permits providers, otherwise exempt from the National Labor Relations Act, to collectively bargain with the state. After this law passed, 40,000 family child care providers in California chose to join the Child Care Providers United (CCPU) union. Their first two contracts, in 2021 and 2023, had increased reimbursement rates, improvements to payment procedures, and investments in retirement, health care, and training.

A similar model is being pushed to be extended for In-Home Support Service (IHSS) workers. Over half-a-million IHSS workers provide support services to aged, blind, and disabled workers in CA. These critical IHSS workers are severely underpaid and are forced to bargain with local, private, nonprofit agencies, which themselves receive funds through county programs. This highly decentralized, disorganized, and underfunded process leaves the average IHSS worker making only around $16.50/hr, with major differences in standards from agency to agency. AB-1672, which passed the Assembly in 2023 and is on hold until 2024, aims to improve this system by making the state the employer and by establishing a statewide bargaining process.

Another industry gaining the attention of the state is the health care sector. Through SB-525, awaiting a decision by Governor Newsom, the state would establish minimum wage schedules well-above the state minimum. Health care workers, depending on the specific nature of their employer, would see their minimum wages increase to $21/hr in 2024, and would reach $25/hr by as early 2026 or as late as 2033.

The broadest, but also least directed and sustained example of moving towards sectoral bargaining in California was in the recently-signed 2023-24 Budget Act (AB-102). Without much fanfare, the budget allocated $3m to the Industrial Welfare Commission (IWC), which has the authority to set wages and working conditions for specific industries. Even though the IWC has existed for 110 years, it’s been denied any funds to operate for the past two decades. Despite this, it still has 17 wage orders for different industries currently in effect.

Thus, its budget revival marked potential for new actions, though its directive was temporary, limited in reach, and unspecific. The Budget Bill directed the IWC to begin operations in 2024 and cease operations 10 months later—with priority for industries with 10 percent of workers below the federal poverty line. This broad-based momentum towards sectoral bargaining was fleeting: the September 2023 Fast Food Council compromise was attached to SB-105, which defunded the IWC once again.

Lessons to be Learned

This movement in California is promising, but is far from what is seen in the Nordics. As of now, the Fast Food Council only has operational authority for 5 years. Only four industries have any specific coverage, and in one of them, health care workers, the scope of content is limited to the minimum wage, and there’s no ongoing structure for new negotiations. To more align with the Nordic Model, all industries in California would need permanent bargaining structures, with coordinated negotiations handled by representatives for both workers and management, and comprehensive issue coverage. Given lower levels of union density and employer associations, California should consider automatic extensions of sectoral agreements to nonparticipants. The existence of the IWC, while once again defunded, does provide a formal entry point for organizers to push for full sectoral bargaining.

Nick Warino is a researcher for SEIU Local 1021, though everything above is based on his own research and views, and does not represent SEIU.