In last week’s discussion of the job guarantee, a lot was said about the “dignity of work” and other things of that sort. I’ve mostly avoided that topic because I am more interested in technical details than philosophical concepts at this point in my life. But the questions of work — whether it is good or bad, fulfilling or alienating, dignified or exploitive — are nonetheless interesting ones that I think are worthy of some intraleft debate.

My view on work is generally negative. Work swallows up your time, tends to subordinate you to others, and is usually not very fun. For the time being, work is a necessary evil because we need the things it produces, but it would be nice to keep it to a minimum and have more leisure.

The pro-working side says instead that work is a source of meaning, dignity, and social status. People want to feel like they are contributing and work gives them that feeling. People also want to do things and work gives them things to do. On this view, work is its own good even separate from the output it produces and the income it delivers to the individual worker.

Below are reasons for doubting the pro-working view.

Are Most People Undignified?

We talk a lot about work, but rarely about how work is distributed across the entire population. All labor market statistics exclude young children from their denominators, many exclude everyone who is not actively looking for work, and some even exclude all but a narrow range of people between the ages of 25 and 54. These kinds of statistics are useful for many purposes, but if we want to talk about work and dignity, then we really need to view the complete society at once.

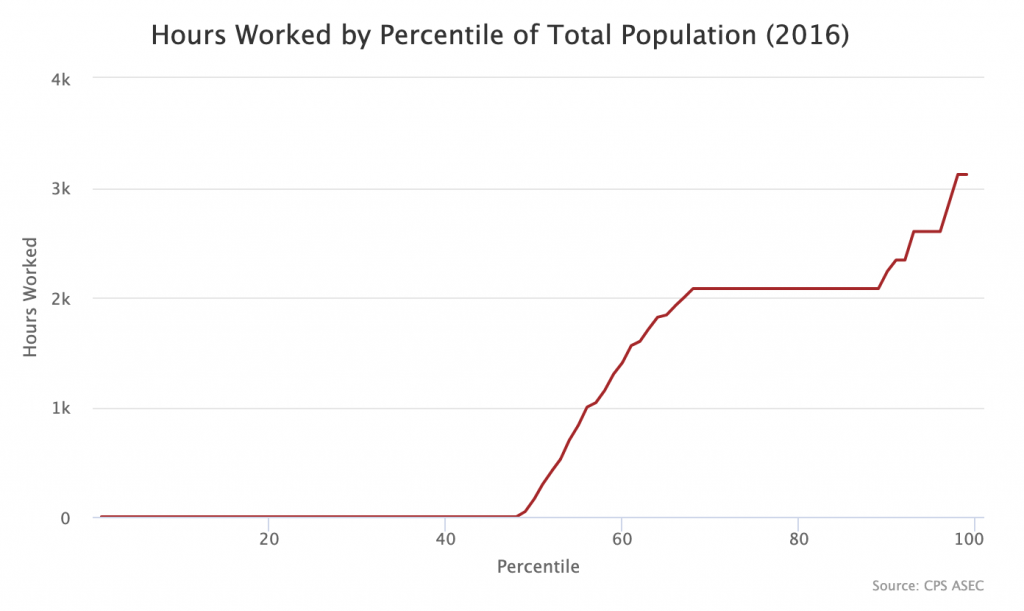

This is what I do in the below graph, which shows how many hours each percentile of the population worked in 2016.

If you move your cursor from left to right, you see percentiles 0 through 48 worked no hours in 2016. This means 48 percent of the population does not work at all. If you continue moving your cursor, you see percentiles 49 through 67 worked less than 2,080 hours. This means only 33 percent of the population worked full time or more in 2016.

It seems strange to me to say deep fulfillment and meaning is connected to something that one-half to two-thirds of the population are not doing in any given year. And beyond being strange, it is kind of problematic.

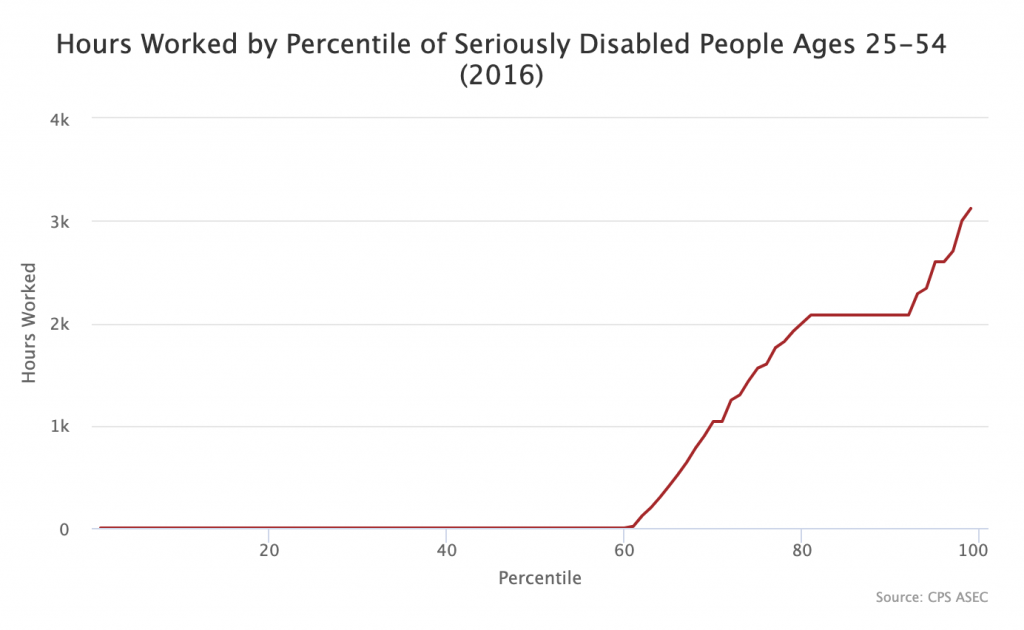

Even if you say we need to exclude children, students, and elderly people from the mix (a point I disagree with), there is still the matter of working-age disabled people. The below graph shows how much they work.

Around 60 percent of working-age disabled people do not work at all and only 20 percent work full time. If we are saying work is key to dignity, then we are saying that work-limited disabled people cannot have dignity.

Proponents of the pro-working view will often make a distinction between those able to work and those not able to work. Such a distinction makes sense when you are talking about such questions as who should be expected to work, but it is hard to see what this distinction has to do with dignity. If being out of work makes you undignified, then it makes you undignified whether you are able to work or not. If there is something magical in the rhythm of working, in the feeling of accomplishment, and in contributing, then it must be that those incapable of working simply cannot access that and necessarily have diminished lives.

Is that the left position on disabled people these days?

People Really Do Not Like Bad Jobs

Much is said about the demonstrable misery unemployed people go through. Some of that seems to be related to negative social attitudes and stigma, which I discuss more in the next section. But it nevertheless is the case that, on average, unemployed people are quite a bit more unhappy than employed people. However, not all jobs are average jobs. Many are below average. And some research indicates that people actually hate these bad jobs more than they hate being unemployed.

Here is one study out of Australia:

Moving from unemployment into a high quality job led to improved mental health (mean change score of +3.3), however the transition from unemployment to a poor quality job was more detrimental to mental health than remaining unemployed (−5.6 vs −1.0).

Here is another from the UK, written up by Olza Khazan at The Atlantic

Compared with adults who remained unemployed, formerly unemployed adults who transitioned into poor quality jobs had higher levels of overall allostatic load, log HbA1c, log triglycerides, log C-reactive protein, log fibrinogen and total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio.

[…]

Formerly unemployed adults who transitioned into poor quality work had greater adverse levels of biomarkers compared with their peers who remained unemployed. The selection of healthier unemployed adults into these poor quality or stressful jobs was unlikely to explain their elevated levels of chronic stress-related biomarkers.

The upshot of all of this is that good jobs are better than being unemployed, but bad jobs are worse than being unemployed, which seems quite intuitive to me.

Of course advocates of a job guarantee will insist that they are going to provide good jobs. But, given all the constraints the program has to operate under (low capital, low skill, countercyclical, etc.), this is a little hard to believe. In any case, it seems at least certain that in some areas of the country, the jobs doled out through such a program will very much resemble the awful jobs handed out under the country’s last major workfare program.

To be sure, bad jobs can be a necessary evil in some cases. The production of adequate amounts of output currently requires people do more than a few really unpleasant tasks. But the weird thing about the job guarantee in particular is that its very design requires that the tasks be unnecessary, meaning that we can go without them being done. So there is a very real risk in all of this that we end up offloading people into unpleasant and unnecessary jobs that actually make them less happy than simply being unemployed and receiving a decent benefit income.

Social Attitudes Towards Work

Although things like the inherent dignity and happiness that comes from work are contestable, the fact that social attitudes are currently very pro-work seems hard to deny. That parts of the American left of all groups are saying that the major problem in one of the highest income countries in the world is that we don’t have enough people out there working every day is its own testament to just how strong the pro-work sentiment is in American society.

But we should not allow this social observation to settle the work question for us. After all, attitudes towards work vary across societies and time. Indeed, we have seen major transformations in who works and how long in our own society in just the past century.

For instance, elderly people rarely work these days and the fact that more are working now than in the recent past is seen by many as a national disgrace. Get that: in our society, more work is shameful, at least for some groups.

Young people have seen their employment fall quite substantially over the last few decades as well, with many staying in school longer than they used to. Yet we do not seem to regard that decline in work as a major problem and indeed would find the reversal of that trend (kids dropping out of school and flooding into the labor force) to be bad. And this is not even to mention the end of child labor, which we see as a major humanitarian victory.

When economies grow and progress, what tends to happen is that people work less. Whole groups of people (children, students, elderly) are removed from the workforce altogether and those remaining in the workforce see their workday cut, get more vacations, and become entitled to all sorts of paid leave from work. America has bucked that trend more than most, but even it has made progress in work reduction over the years. Thus to say that social attitudes towards work are in any way fixed or that people crave it down to their core seems to me to be totally incorrect. Social views on work evolve over time, generally in the favor of having less of it, and so we should not proceed politically as if work-glorification is the only option we have.