When Elizabeth Warren released her plan to subsidize center-based child care last month, she was criticized from the left for not including people who care for children at home.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein took to Twitter:

I know this is revolutionary but what if we also stopped harassing women on welfare by acknowledging that caring work is work. Universal childcare credit for stay at home mothers! Wages for housework!

Nishile Mohile echoed that sentiment:

Women’s labor is not free, and they should be paid for the work that they do. Paying for otherwise unpaid household work could even marginally reduce the gender wage gap.

When People’s Policy Project released the Family Fun Pack, which provides free public child care to those who want it and a home child care allowance to those who care for children in the home, it was criticized by some liberals for promoting traditional gender roles.

Kathleen Geier wrote this:

In addition, the child care system should not reinforce gender inequities. That’s why we should take a hard pass on plans (such as Matt Bruenig’s otherwise excellent child care proposal) that would pay parents to stay home to take care of their kids on a permanent basis. Such schemes tend to incentivize traditional gender roles instead of abolishing them.

As a descriptive matter, Geier goes off the rails here a bit. A home child care allowance does not pay parents who stay home “on a permanent basis.” Rather, it pays them for as long as their kids are of child care age (from 6 months old to 3 years old). Additionally, a choice between free child care and a home child care allowance does not “incentivize” anything. Rather it provides equal financial support to both options, neutralizing any financial incentive to do one or the other.

But if we can put aside these confusions, it’s clear what she is getting at: relative to a system that only has free child care, a system that has free child care and a home child care allowance will result in more people doing home child care. And at least in the near term, it will be mostly women who elect to receive the home child care allowance. This would then cut against having equal numbers of men and women in the labor market (though it would not cut against having equal numbers of men and women doing paid work).

Historically, in the US and abroad, leftists and liberals have found themselves completely unable to resolve these basic questions: Is paying home child carers a radical recognition that domestic work is work and should be paid or is it a way of promoting women’s domesticity? Is working in the capitalist labor market liberation from the home and spouse or is working in the home liberation from the capitalist labor market and boss? You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

For me, finding an answer to the apparent conundrum is made easy by the recognition that people are going to do home child care whether you pay them or not. There just are a lot of people who have a strong preference for it, especially lower and working class people (whose labor market alternatives are often awful), rural people (for whom center-based care is logistically impractical), and immigrants. Then there are also people who have cultural preferences for it, which appears to be especially present in the Latino community.

Refusing to pay these people will likely result in some of them joining the labor market (e.g. out of financial necessity), but millions others will continue to do home child care without being paid. Not paying them will spike poverty and inequality, as well as leading to a state of affairs where more men are doing paid work than women.

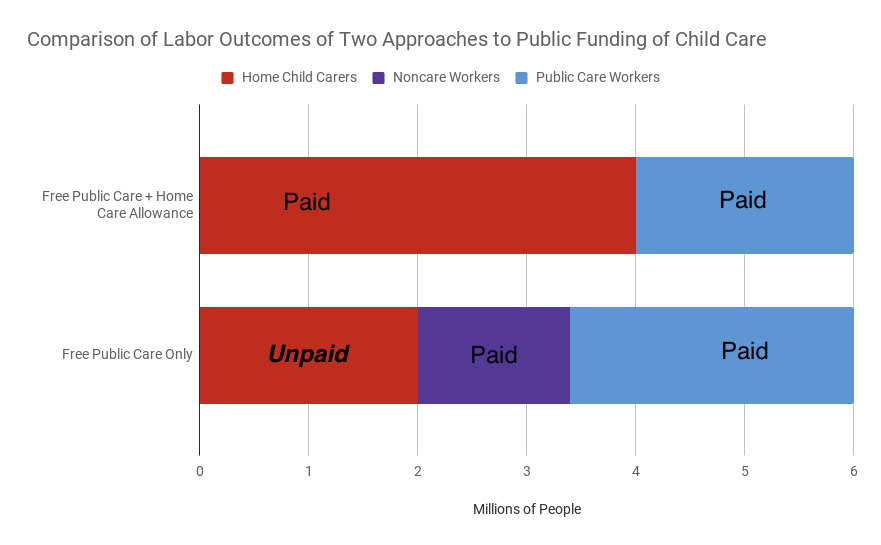

To understand this divide clearly, it might be helpful to use rough numbers to illustrate the actual choice at issue here.

Suppose there are 4 million births a year. That means there will be 10 million kids between the ages of 0.5 and 3 at any given time. All 10 million of those kids have to be cared for by someone. Further suppose public centers will have a 3 to 1 ratio of carers to children and home child carers will have a 1 to 1 ratio (under the Family Fun Pack, this means home child carers will receive one-third of the pay of public child carers).

In a system that had free public child care and a home child care allowance, we can suppose that perhaps 6 million kids will be in public child care and 4 million kids will be in home child care. This creates a situation (top bar on the graph below) where there are 2 million public child care workers and 4 million home child care workers.

In a system that only had free public child care, we can suppose that half of the home child carers have to go into the labor market, leading to a situation where 8 million kids are in public child care and 2 million are at home. This creates a situation (bottom bar in the graph) where we have 2.6 million public child care workers, 2 million home child care workers, and then 1.4 million extra noncare workers.

In this scenario, by refusing to pay home child carers (who are almost all women), you can flush 2 million of them into the labor market, though 0.6 million of them wind up doing the same care work they were doing, only now in a public center.

On the one hand, this can be seen as a victory for gender equality in some frameworks since it increases the number of women in the formal labor market. On the other hand, this can be seen as a loss for gender equality in some frameworks as it makes it so that 2 million home child carers (almost all of whom are women) do not receive pay for their work. And of course, outside of the specific gender frame, not paying these people will create poverty and inequality, something I personally cannot tolerate.

Refusing to compensate certain kinds of work will no doubt reduce the amount of it that is done at the margin, but only at the expense of crushing the people who keep doing it without being paid. To me, the no-brainer way forward is to pay all child care workers, not just public child care workers, and try to work through cultural mechanisms to change the fact that the child care sector employs far more women than men (a problem not unique to home child care, but also present in center-based care).