Of all the welfare state topics, student benefits manages to consistently attract the most incoherent and weird arguments, and the recent spate of arguments on this front are no exception. In the last week, a student benefit dustup has been instigated by Pete Buttigieg ostensibly being against free public college for millionaires and billionaires while Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are ostensibly for it.

This has set off the usual round of commentary about how Buttigieg is arguing for means-testing while Warren and Sanders are arguing for universalism. But what’s weird is that everyone involved here is basically proposing the same policy.

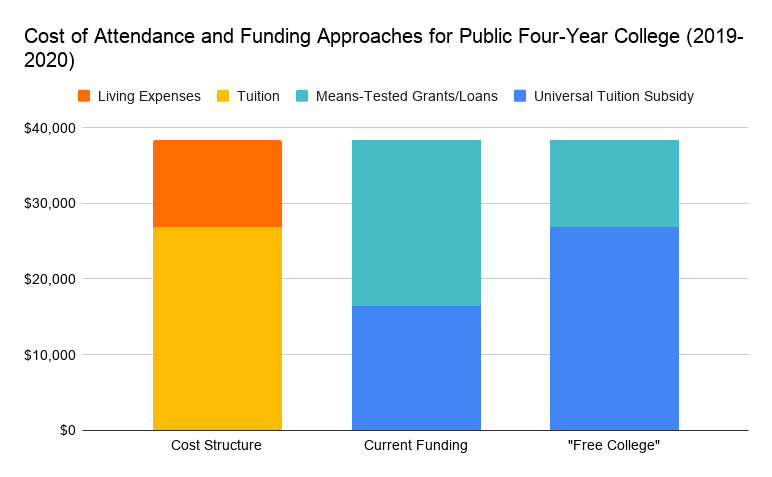

For students, the unsubsidized cost of attending a public university is the unsubsidized tuition plus living expenses. Currently that cost is funded through a universal tuition subsidy that covers around 61 percent of the unsubsidized tuition plus means-tested grants and loans to cover the rest of the tuition and the living expenses.

Warren and Sanders both propose to increase the universal tuition subsidy to 100 percent of the unsubsidized tuition, but also propose to continue using means-tested grants and loans to cover the rest of the cost (i.e. the living expenses).

Buttigieg proposes to maintain the current level of universal tuition subsidy while increasing the generosity of the means-tested grants and loans used to cover the rest of the tuition and the living expenses.

So in categorical terms, all three plans look the same. They use a universal tuition subsidy plus means-tested grants and loans to cover the cost of attendance. This means that the categorical distinctions people make between the plans aren’t really present.

Buttigieg and his supporters claim that he does not want to provide benefits to students from affluent families, but he does not propose to eliminate the universal tuition subsidies that already do that.

Warren, Sanders, and their supporters claim that they are carrying the mantle of universalism and yet both still use means-tested grants and loans to cover the living expenses.

The precise mix of universalism and means-testing differs between the plans and you can of course favor one plan over the other based on those differences. But they all use a mix. There are no big philosophical distinctions to be made between them.

There are also no real practical distinctions to be made between them. In all three plans, students will still need to fill out a bunch of financial aid paperwork to determine what, if anything, they get from the means-tested portions of each plan. The experience won’t differ, though the precise benefit amounts might.