Last week, Jason Furman published a piece in the Wall Street Journal in which he called for phasing out the Child Tax Credit (CTC) “more rapidly as incomes rise, focusing help on those who need it most.” A few months ago, David Shor and Simon Bazelon called for the same thing.

The general idea that welfare benefits should be means-tested like this in order to reduce spending and target spending to those in need is extremely prevalent in American politics, especially among elected officials. In fact, this idea is so prevalent that it has hardened into a kind of common sense conventional wisdom among most of the American policymaking class.

But this isn’t conventional wisdom everywhere in the world. In fact, there are some places and some policymaking communities that find the idea of means-testing a child allowance totally perplexing.

Earlier this month, the Norwegian statistical agency published a paper about the current means-tested CTC in which the authors suggest that American policymakers “consider the obvious alternative of financing a generous universal child benefit by changing the overall income tax system.”

The argument in this paper is straightforward and clearly correct:

- A benefit phaseout is identical to a tax. Thus, reducing a family’s CTC by 5 cents for every dollar they earn beyond, say, $100,000 should be understood as a very narrowly-targeted 5 percent income tax that raises a relatively small amount of revenue.

- The revenue raised by this “phaseout tax” could be raised by other kinds of taxes, including normal income taxes that fall on all tax units with income beyond the phaseout threshold, not just tax units with children in them.

- Replacing this phaseout tax with a normal tax on all tax units allows you to lower the tax rate while still raising the same amount of revenue.

- Replacing the phaseout tax with a normal tax on all tax units lowers the marginal tax rate of tax units with children while increasing it for tax units without children. Because tax units with children are more likely to reduce labor supply in response to taxes than tax units without children, this shift will result in a higher labor supply.

The upshot of this analysis is that, from a public budget perspective, tax-financed universal child benefits are not more costly than means-tested child benefits and, from a total economy perspective, tax-financed universal child benefits are less costly than means-tested child benefits because they generate more labor supply.

So when people like Furman call for a more strictly means-tested CTC, they aren’t actually proposing a policy that reduces spending. Rather they are advocating for raising revenue through the use of a clearly inferior and inefficient approach to taxation. As the paper authors put it:

A tax financed universal scheme is preferable, both from an efficiency and redistributional point of view. A universal scheme is likely also preferable from the perspective of compliance and administrative burdens.

Illustrating the Point with US Data

In the Norwegian paper, the authors apply a hypothetical CTC-like benefit to Norwegian income microdata to illustrate their argument. Below, I do something similar to what they did, but with US data, specifically the 2019 CPS ASEC. Ideally, of course, you would use IRS microdata for this purpose. But I do not have access to such data, and so, for the purposes of this illustration, I am going to use the tax variables in the CPS ASEC.

Imagine the US had a $3,000 per year universal child allowance paid out to all children below the age of 18. This would cost $210.5 billion per year.

From there, imagine that we added a CTC phaseout tax equal to 5 cents per dollar of income beyond $200,000 for single filers and $400,000 for married filers. Under this kind of phaseout tax, a married family with one child would effectively pay a 5 percent tax on income between $400,000 and $460,000. If they had two children, it would be a 5 percent tax on income between $400,000 and $520,000. And so on and so forth.

With the CPS microdata, you can go through each tax unit with children in it, figure out how much income they have that is in the phaseout zone, and then add up all of that income for every affected tax unit. Doing that with this data generates the conclusion that this phaseout tax would be applied to $85.9 billion of income. Since the tax is 5 percent of this $85.9 billion base, the phaseout tax generates $4.3 billion of revenue.

The tax units that are affected by this phaseout tax have, on average, $82,000 of their income subject to the 5 percent levy.

With this $82,000 figure, we can now present the relevant question squarely: if you wanted to raise $4.3 billion of revenue with a normal tax on all income between $200,000 and $282,000 for single filers and between $400,000 and $482,000 for married filers, what would the tax rate need to be? The answer is 2.2 percent.

We can also ask a slightly different question: what would the rate need to be if you were trying to raise this revenue with a normal income tax on all income over $200,000 for single filers and over $400,000 for married filers (so without the $82,000 cap)? The answer in this data is 0.6 percent.

As the Norwegians already pointed out: a 2.2 percent (or potentially 0.6 percent) tax on all tax units with income beyond the threshold is better than a 5 percent phaseout tax that falls only on tax units with children with income beyond the threshold. It increases total labor supply. It ensures that all families benefit from consumption smoothing when they add a child to their family. It makes the administration of the child allowance much easier and thereby makes it so that far fewer poor people are excluded from the benefit by administrative burdens. It increases horizontal equality in the society.

There is literally not a single thing that the means-tested approach is better at than the universal approach. When understood properly, the means-tested approach costs the exact same amount of money and has a massive list of negatives that the universal approach does not. It is a completely indefensible approach to benefit design.

I ran this same exercise at different phaseout thresholds and generated the same basic conclusions. A 5 percent phaseout tax that hit at $100k for single filers and $200k for married filers raises the same amount of revenue as a normal 2.2 percent tax applied to all income between $100k and $160k (for single filers) and between $200k and $260k (for married filers). Similarly, a 5 percent phaseout tax that hit at $50k for singe filers and $100k for married files raises the same amount of revenue as a normal 2.2 percent tax applied to all income between $50k and $105k (for single filers) and $100k and $155k (for married filers).

If you want to reduce the net fiscal cost of a child allowance, it makes sense to increase taxes on the middle class, as Furman and Shor argue to do. But the best way to do that is not a phaseout tax but rather a normal tax, this being the actual difference between a means-tested child benefit and a universal child benefit.

Nonsense Accounting Destroys Brains

So far in this post, I’ve intentionally described the net fiscal impact of a phaseout as being the revenue raised by a phaseout tax. This is how the Norwegian paper approaches it. And it is, from a policy analysis perspective, clearly the proper way to approach it. The question of whether to use a phaseout tax (means test) or a normal tax (universal benefit) is an optimal taxation question, not an optimal government spending question. You analyze it using theories and elasticities developed in the tax literature.

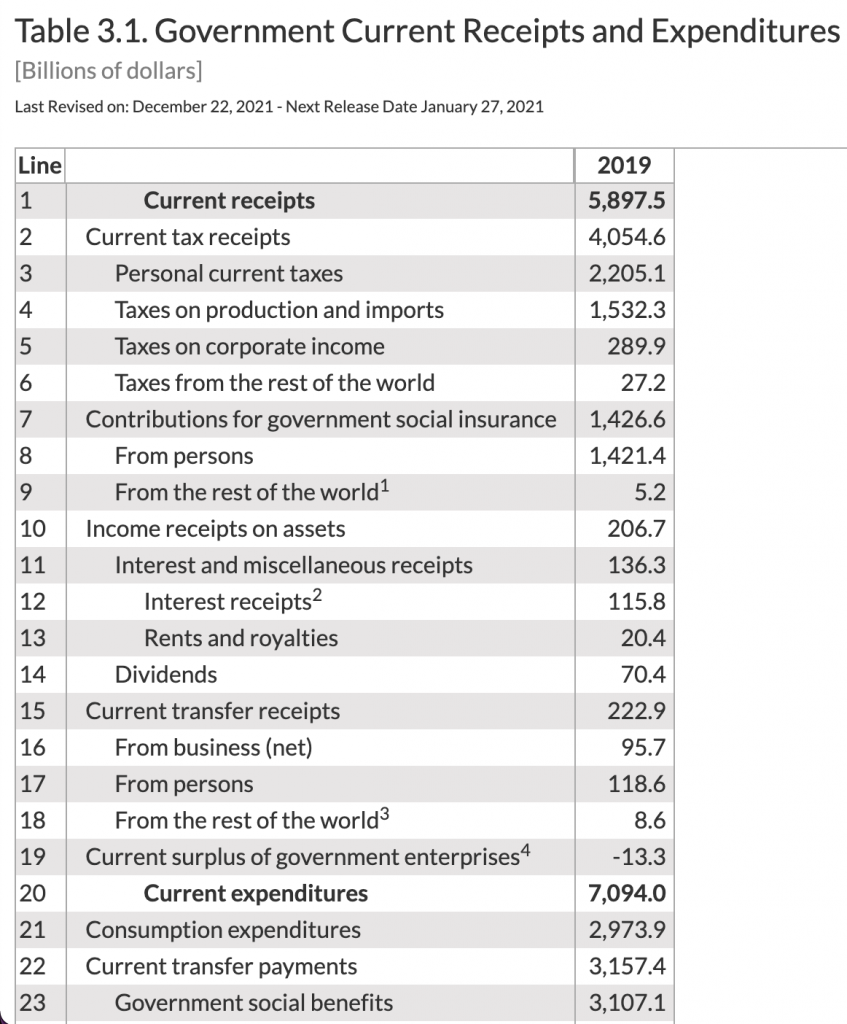

But this is not how our national accounting treats these things. Under the current approach to refundable tax credits, the revenue raised (or “money saved” if you prefer) from means-testing a refundable tax credit is deducted from the “Government social benefits” row (line 23 below) while the revenue raised from a similarly-structured normal tax is added to the “Personal current taxes” row (line 3). So in the illustration above, the $4.3 billion raised by the 5 percent phaseout tax is subtracted from line 23. But the same $4.3 billion raised by the 2.2 percent or 0.6 percent normal taxes is added to line 3.

It seems insane to allow this accounting convention to steer policymakers into making dramatically worse policy design decisions. But that is exactly what is happening in the case of the child allowance debate, both because some policymakers are moved by which quantities show up in which row, but more broadly because this accounting convention is so deeply burrowed into so many people’s brains that they really do think phaseout taxes are spending-reducers rather than revenue-raisers.

What’s especially odd about this is that these accounting conventions are not set in stone. The current treatment of refundable tax credits did not even begin until 2015. Prior to 2015, refundable tax credit payments that exceeded a tax unit’s tax liability were counted as “Government social benefits” while all other refundable tax credit payments were deducted against “Personal current taxes.” After 2015, the accounts were updated to count all refundable tax credit payments as “Government social benefits” regardless of whether they exceeded tax liability. This change retroactively added hundreds of billions of dollars to the historical tax bill while adding the same amount to the historical welfare bill. Of course, in real life, nothing actually changed.

National accounts are useful and interesting. But if you let them take over your mind, you wind up in some very dumb places. The completely indefensible means-testing consensus is one such place.