Within the US constitutional system, the power to make laws is vested in Congress. This power includes the power to raise revenue through taxation and other means, to borrow money, and to engage in public spending. The president is then required to execute these fiscal laws as written.

There is a potential problem in this structure, which is that Congress could pass laws directing the president to spend a certain amount of money without passing laws to finance that spending. In this scenario, it is impossible for the president to follow the law. If he executes the spending by unilaterally financing it through tax hikes, bond sales, or similar, then he has usurped financing authority that is vested solely in Congress. If he unilaterally forgoes some or all of the spending mandated by Congress in order to stay within the financial constraints, then he has usurped the spending authority that is vested solely in Congress.

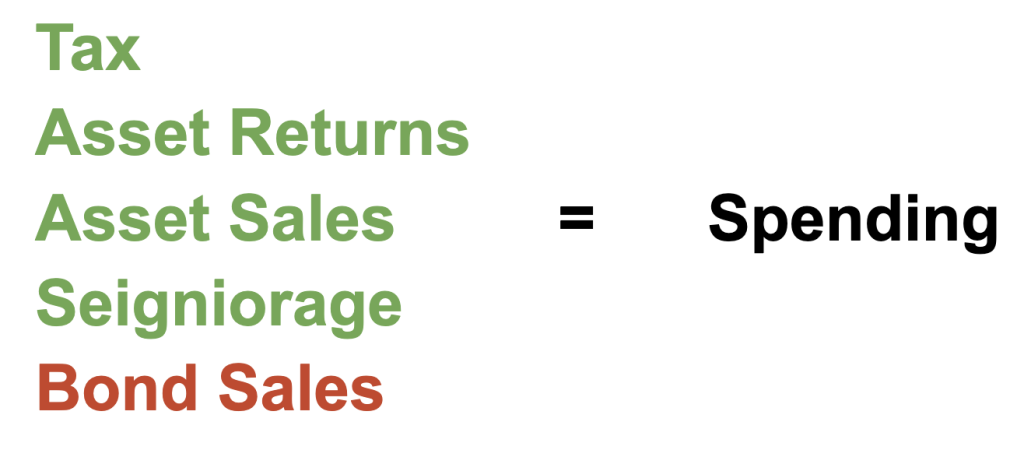

As far as I know, this potential problem has never arisen historically. Before 1917, Congress financed all of the spending it mandated, including by authorizing each and every bond sale. After 1917, Congress made it so that the president was always authorized to sell bonds in order to finance any spending that exceeded other revenue sources. So, in this scenario, bond sales became the residual funding mechanism used to ensure that the following equation was always in balance.

But this permanent authorization to sell bonds to balance this equation has one caveat, which is that it is subject to a debt limit. This means that when the total face value of the bonds outstanding hits a certain dollar amount, currently $31.4 trillion, the president is no longer authorized to sell bonds in order to balance this equation.

But if he can’t use bond sales to balance the equation, then how is he supposed to balance it?

As discussed already, he can’t refuse to do spending that Congress has directed him to do. He also can’t unilaterally raise taxes or sell off public assets like the USPS or federal lands. The return on federal assets is not something that you can just dial up through executive fiat as it depends on market conditions. Lastly, the right to engage in seigniorage (i.e. money creation) is something that the Federal Reserve has, but not something the Treasury is generally regarded as having.

So, if you approach this issue conventionally, you are forced to conclude that, when the debt limit is hit, it is literally impossible for the president to follow the law, that Congress has essentially passed a set of laws that direct the president to do X and not-X at the same time.

All of the unconventional approaches to this conundrum work by finding authority for the president to do one of the financing activities that he appears to not be allowed to do. So far, this search for authority has primarily focused on the last two financing streams in the equation above: seigniorage and bond sales.

Although the Treasury is not generally regarded as having the right to engage in seigniorage, 31 USC 5112(k) gives the Treasury the authority to mint platinum coins in any denomination. On its face, this could be read as giving the Treasury unlimited authority to engage in seigniorage provided it is done through the minting of platinum coins. And logically, if such authority exists, and if the president cannot sell more bonds because of the debt limit, then the president must use this kind of seigniorage to finance the spending mandated by Congress. It is the only way for the president to not violate any laws.

Although the debt limit appears to forbid bond sales beyond $31.4 trillion, this dollar amount is arrived at by adding up the “face value” of all of the outstanding bonds. But the face value of bonds can be manipulated by changing the bond’s coupon. For example, the treasury could issue bonds with a face value of $0 that only paid its holders a set amount of interest each year for a certain number of years. In this scenario, people would still buy the bonds in order to receive the interest, but there would be no principal and thus no face value. As with the seigniorage scenario above, if the Treasury has the authority to issue zero-principal bonds, then the president must legally do so in order to finance the spending mandated by Congress.

Beyond zero-principal bonds, there are two other approaches to engaging in bond sales despite the debt limit. The first is to point to the part of the 14th amendment that says “the validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned” in order to argue that the debt limit statute is itself unconstitutional. The second is to rehearse the point above that the situation set up by the debt limit makes it literally impossible for the president to not violate the law (whether tax laws, debt laws, or spending laws) and then say that, between these lawbreaking options, violating the debt limit law is the least lawbreaking course of action.

The president could also illegally raise taxes or illegally sell off public assets to balance the equation, though so far nobody has really advocated for those lawbreaking approaches.

In the last week or so, there has been a bit of a crackup among liberal pundits on this topic, with many now suggesting that Biden can’t use any of these approaches and has to strike a deal on raising the debt limit. According to this argument, none of these alternative approaches will work because ultimately the conservative Supreme Court will rule against them.

But liberals who say this remain very unclear about what they think the Supreme Court ruling would actually be. If you keep the question abstract, you can just say something like “the Supreme Court will uphold the constitutionality of the debt limit” or something very reasonable-sounding like that. But this abstract gloss misunderstands the actual legal question that the Supreme Court would have to answer, which is not whether the debt limit is constitutional, but rather what must the president do when Congress mandates an amount of spending that exceeds the amount of authorized financing?

Is the Supreme Court going to rule that, in that scenario, the president has the constitutional authority to unilaterally disregard some of the spending Congress has mandated the president to do? In this scenario, does the president get to choose what spending to disregard, sort of like a line-item veto, which the court has already ruled is unconstitutional even when Congress specifically passes a law giving the president line-item veto rights? Could Biden eliminate the entire Department of Defense once the debt limit is hit in order to get aggregate spending down to the levels financed by Congress?

There is no coherent way for the Supreme Court to actually resolve this kind of legal issue and the most ridiculous possible way for them to resolve it — especially within conservative jurisprudence — would be finding that the debt limit statute, without explicitly saying so, gives the president the authority to ignore whatever spending laws he wants in the event of a debt limit breach. Given these difficulties, it seems far more likely to me that the Supreme Court would just decline to rule, citing the Political Questions doctrine.

Based on all of the above, my current thinking on the best way for Biden to deal with the debt limit is to sell zero-principal bonds. These would not count as debt under the wording of the debt limit statute because they have a $0 face value. If this was challenged, then the administration has three different defenses to the challenge: that zero-principal bonds do not contribute to the debt limit, that the debt limit is unconstitutional, and that illegally selling bonds is no more unconstitutional than illegally raising taxes, selling assets, or cutting spending.

But whichever course of action Biden chooses, we should be clear that he has other options than agreeing to crack the whip against America’s poor.